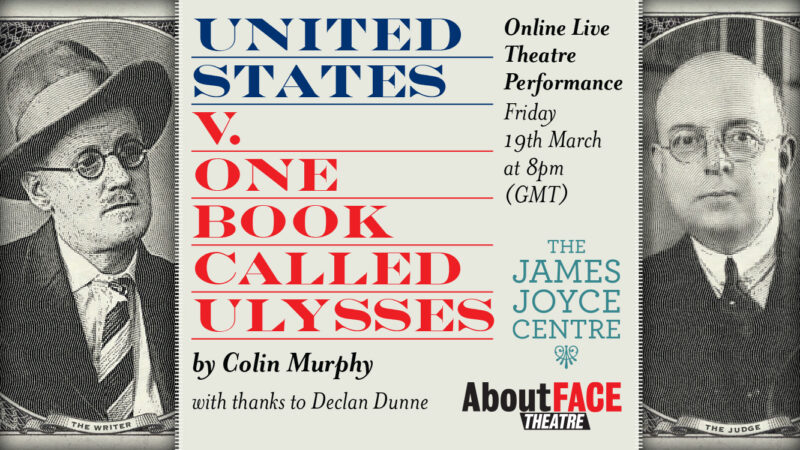

In a rehearsed reading of the new play United States v One Book Called Ulysses over Zoom, a group of actors from Ireland and the United States took to the virtual stage to bring to life the drama of one of the greatest literary trials of the 20th century. The show followed the individuals involved in the case for allowing James Joyce’s Ulysses to be published in the US, despite its perceived obscenity.

The hypocritical nature of the obscenity laws at the time was a running theme of the show. The actors portrayed how those in charge of managing “obscene” books often read the books they seized themselves, despite regulations to the contrary. One scene demonstrated this double standard, in which the attorney representing the United States government allowed the men working at his office to read the novel, while maintaining that it was too obscene for public consumption. In the words of the actor, “it’s a literary masterpiece, but it’s obscene”.

Through the legal argumentation of attorney Morris Ernst, the show also explored how ambiguous the definition of “obscenity” was – by pointing out that antisemitism and racist sentiments were considered okay at the time, while a woman’s sexuality was not. This depicted just how subjective the laws were, while also demonstrating the fear of female sexuality and its association with depravity that existed at the time, and still lingers on today.

Another theme explored through the legal argument was the subjective nature of the literary canon, and the debate surrounding whose voices we consider educated enough to comment on matters of literature. A point of contention brilliantly staged between Anna Nugent (playing the US Attorney) and Charlie Kranz (playing attorney Morris Ernst) involved whether expert opinion should be considered in the case. The dynamism of this scene was maintained despite the virtual setting, with ensemble members using costumes to differentiate their learned personas.

The greatest setback to the show, at times, was the narration and framing device. Named as “the Voice of Time”, the show featured a narrator who added context and descriptions, inspired by a real-life group known as “The March of Time”. The group reported on significant news, as explained in the post-show talk by author Declan Dunne (whose book Set at Random provided inspiration for the play).

In the early part of the show, the narrator not only introduced each character, but also described their interactions, and this is where the pacing and characterisation fell flat. The narration fell foul of the old “show, don’t tell” adage – by dictating character interactions rather than allowing the characters to interact with each other. The show became tedious, and began to feel as though we were receiving a summary of the plot rather than watching the show.

Despite this, the show picked up steam in its latter half, and by the end had the audience heavily invested in the verdict of the trial, despite its already being known. Overall, the show masterfully adapted one of the most dramatic legal trials of the 20th century to the virtual stage. The actors made clever use of costume changes and camera capabilities to present the illusion of reality over Zoom, whilst the plot, despite originating from a lawsuit, was undeniably exciting. I look forward to seeing how the show navigates the digital world and, hopefully, the live theatre world post-pandemic.