When most people think of sailing they may be inclined to think of it as a laid back leisure activity, something privileged people do in their spare time while basking in the sun and enjoying life. Watch any footage of an Olympic sailing race, however, and that perception will shatter fast.

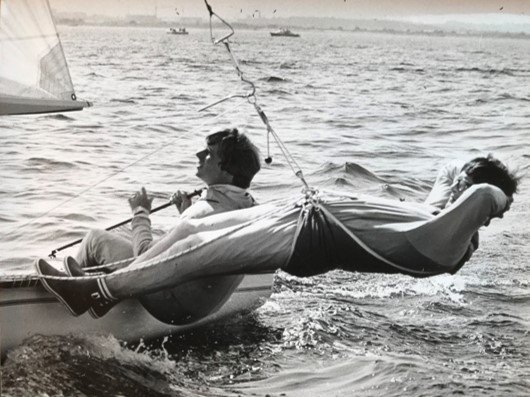

A sailing race, in a word, is intense. A sailor has to concentrate on countless different things all at once, focusing on their peripheral surroundings all the while managing what needs to be done inside the hull whether it be tacking, pulling in the main sheet or laying flat out of the boat with a strap around your waist to maximise speed. And what’s more, races can take up to two to three hours to complete. One can easily be convinced that sailing is among the most mentally and physically exhausting sports there is.

Nobody is more familiar with this than David Wilkins – the man who has represented Ireland as an Olympic sailor five times and won silver.

“What most people don’t realize is the level of fitness that you need for sailing. It’s certainly not gin and tonics. It’s very much very physical”, Wilkins said.

According to a study from Britain, the energy exerted over the course of a day of racing in the Olympics is the equivalent to that of a three-quarter marathon.

Wilkins, originally from Malahide, has a storied life. With five trips to the summer games, having competed in all but one in a 20-year span from 1972 to 1992, he has the most Olympic caps of any Irish athlete ever and in 1980 he won a silver medal.

What most people don’t realize is the level of fitness that you need for sailing. It’s certainly not gin and tonics. It’s very much very physical

But Wilkins will tell you he should have won more. Both in 1972, his first trip, and in 1988, his fourth, he reckons gold was in his grasp were it not for some cruel luck getting in the way.

Wilkins was just 22 years old in 1972 when he went to Munich to represent Ireland for the first time. At that point he had been sailing for just seven years having only started at 15 – a relatively late age to begin the sport.

This was also his final year at Trinity where he had also sailed as a student for Dublin University Sailing Club (DUSC).

DUSC at that time was stacked with some phenomenal sailors. According to Wilkins, back then everyone in the country who could sail went to Trinity and as a result there was fierce competition to even make the team. One student who had finished third in the Fireball World Championships didn’t even make the cut, Wilkins tells me.

It was around that time when the Trinity sailing team would win the Northern Universities Championships nine years in a row.

Wilkins’s final year of sailing, however, was more focused on preparing for Munich than it was sailing for Trinity.

By 1972 Wilkins had established himself as an up and coming sailing phenomenon having won the European Junior Championships at just 17 and Ireland’s first ever World Youth Championships at 19.

In his final year at Trinity, preparing for Munich was difficult enough, having to do so on a tight budget while also balancing college. But Wilkins was also in search of a crew mate and was specifically looking for someone who was heavy enough to make up for his relatively slight build as the Tempest boat – the boat he would be sailing in the Olympics – needed as heavy a crew as possible.

DUSC at that time was stacked with some phenomenal sailors. According to Wilkins, back then everyone in the country who could sail went to Trinity and as a result there was fierce competition to even make the teamI went to the Trinity rugby team and asked them: ‘Is there anybody who has some sailing experience and is that sort of size?’ And that’s where I found Seán Whitaker

“I’m really good at getting the feel of a boat and being able to tune it to be its best, you know, and what better boat for me than the Flying Dutchman.”

To win a medal in sailing, however, everything has to go right – consistency is paramount. Unlike his first trip, this time Wilkins was indeed consistent, finishing top three in five of the seven races to end the campaign with a second-place finish behind the Spanish.

Wilkins, perhaps deflecting too much away from his own talent, attributed part of their success to a new centreboard which they had delivered just before the race.

“It made a huge difference to the performance of the boat upwind. It just made us lightning quick, when we’d been average upwind”, Wilkins says.

“Going from being sort of average upwind to being very fast, it meant we were in the top couple of boats… So we knew going into the Olympics that we were going to be one of the fastest there if not the fastest. So we were pretty confident.”

After the race when Wilkins had secured silver, the president of the International Olympic Committee at the time presenting Wilkins and Wilkinson with their medal was Irishman Lord Killanin Michael Morris.

“He said it was the first time he’d actually presented a medal to Ireland during his reign as president”, Wilkins says. “So he was quite chuffed about that. And we were obviously chuffed that we could be the ones as well of course!”

The press coverage of Wilkins’s medal winning campaign was somewhat hampered by the sailing course in 1980 being located in Tallinn, Estonia, some 800 kilometres away from the main events in Moscow. Nevertheless, coverage was had thanks to Wilkins himself who effectively served as correspondent for his own races.

“I used to phone up every day to David Burgess, who was the Irish Times sailing journalist at the time and give him a report. At that time, we didn’t have faxes, or emails so the only way we could communicate quickly was by phone each evening. So I gave him a verbal report and then in the morning he was able to write it up.”

“So people said to me: ‘How come the reports were really detailed and accurate and interesting? How did they get that? And I said: ‘Oh, that was me.’”

I’m really good at getting the feel of a boat and being able to tune it to be its best, you know, and what better boat for me than the Flying Dutchman

In 1984, with a young family and unable to get the time off work Wilkins would have to skip what would be his only missed olympics in 20 years. In 1988, however, feeling he had plenty left in the tank, Wilkins came back with a hunger for gold. “I still had the bug for it and I felt that I could have done better and felt we probably should have got the gold medal”, he said.

Having teamed up with Peter Kennedy, a successful sailor in his own right and an Irish laser champion, he entered the Seoul Olympics as well-prepared as ever and perhaps in his best position to win.

“The Flying Dutchman is very sensitive to trim and we just got it so right that we were absolutely flying”, Wilkins said, describing one of the races. “And we sailed away from everybody and were well in front. The only way we could have lost it is either to capsize or something to have gone wrong. Well, it went wrong in a way that you would never imagine.”

What happened, Wilkins explains to me, was that having adjusted their sails exactly right the pair were flying and were well ahead of their opponents but then all of a sudden there was a stark slowdown as if they had just begun dragging along an anchor.

What they discovered was that their centreboard had latched onto a piece of plastic with tar on it – an unbelievable freak occurrence for a boat sailing in the middle of the Sea of Japan. With that they were forced to capsize their boat and attempt to remove the tar – an effort that proved unsuccessful – dropping to nearly last place.

One freak occurrence is frustrating enough but survivable as the scoring rules allow each boat to disregard their worst performance. A second mishap, however, and the prospects for a medal are all but gone.

And a second instance of unbelievable misfortune did in fact happen. In another race, after cruising in the top 4, a container ship intruded into the course forcing them to tack away from the optimal path, putting them at a severe disadvantage. Unable to recover, the pair ended up finishing in 15th place.

“That’s what screwed me in that race and three other guys actually as well. We’d lost out by those two events and if it hadn’t been for that we would have been fighting for a gold medal. We were really quick. We were really fast.”

Had that happened today, Wilkins explains, the race would most likely have been abandoned and started over, but not in 1988. They did make a formal protest but the jury rejected their case.

I still had the bug for it and I felt that I could have done better and felt we probably should have got the gold medal

“So many different things can go wrong in sailing – probably more than most sports. But I guess every sport has its characteristics”, Wilkins says.

He gave it one last try in 1992 in Barcelona, motivated in part by the disappointment of 1988, but was unable to get that second medal he craved finishing at a still respectable 11th place overall.

While Wilkins came so close to multiple more sailing medals, that should not distract from what is such an accomplished life in Olympic sailing. To the contrary, it highlights his greatness as an Olympic athlete in a sport in which success is so fleeting – Annalise Murphy is the only other sailor to have ever won a medal for Ireland.

Wilkins is hailed as a legend among Irishing sailing circles and if there is a GOAT of Irish sailing it would have to be him. The Trinity community can boast that David Wilkins, along with rugby player turned sailing Oympian Seán Whitaker and fellow silver medalist Jamie Wilkinson, is one of their own.