Earlier this week, US President Joe Biden signed into law the recognition of Juneteenth as a federal holiday. The day commemorates the emancipation of enslaved African Americans, and campaigning for greater recognition of the holiday, which falls on June 19th, has ticked away for several decades, but increased exponentially over the past year.

Before Biden’s announcement, almost all 50 states had deemed Juneteenth – a portmanteau of “June” and “nineteenth” – a state holiday. But Juneteenth events, up to now, have largely taken the form of small, local events, with little recognition on broader scales.

Dr Emily Blanck is a history professor at Rowan University in New Jersey, and has been studying Juneteenth and how it is marked for over a decade. Speaking to The University Times several weeks before the day was officially made a federal holiday, Blanck explains that knowledge of Juneteenth was, until quite recently, limited.

“I’ve been studying this now since 2008. And when I tell somebody I was studying Juneteenth, they’d be like: ‘Oh, I’ve never heard of that’”, Blanck says.

But “there’s been more and more movement to sort of make it a bigger national holiday, a push to get states to recognise it”, Blanck adds. “A couple of years ago, we had three television shows feature episodes with Juneteenth.”

I’ve been studying this now since 2008. And when I tell somebody I was studying Juneteenth, they’d be like: ‘Oh, I’ve never heard of that’

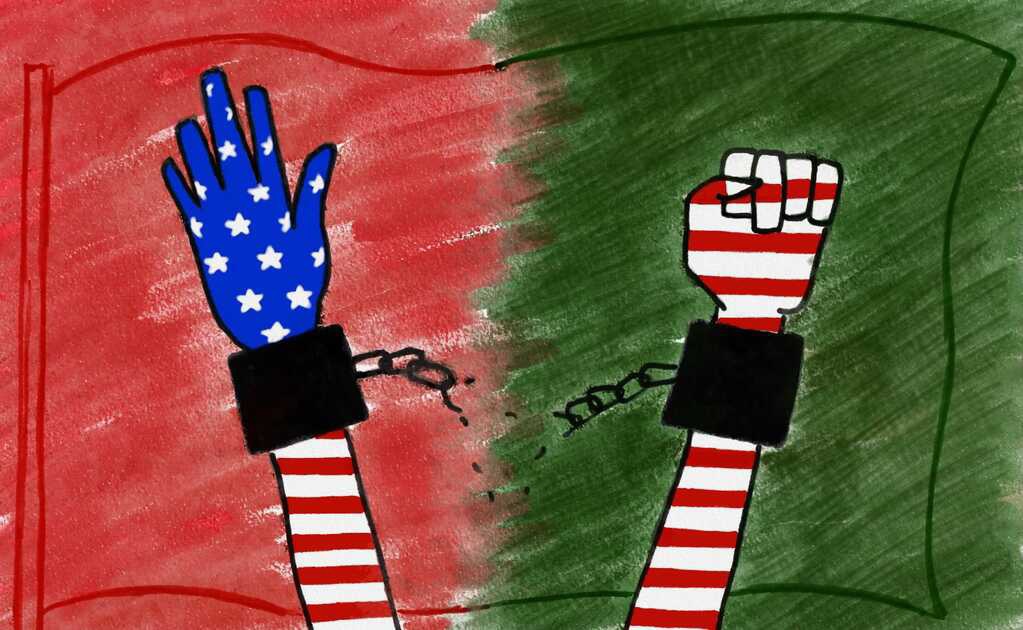

But the growth in recognition of the holiday was spurred, in no small part, by protest: it was the murder of George Floyd in May, 2020 that gave the day something of a refreshed meaning, for both black and white communities in the US. The day has become “a good touchstone for people to really reflect”, Blanck says: “What did emancipation mean in the United States? Are we really living into that?”

Sydney Jackson, a 22-year-old activist from Chicago, co-organised one of the many events to mark Juneteenth last year: a peaceful rally which served as both a celebration of black pride and empowerment, and a demand for justice and equality for black people in the wake of Floyd’s death. Jackson tells The University Times that for them personally, “it’s a time for us to really focus on, not even just the word celebration, but fellowship and kinship”.

So will greater recognition of the event change its meaning? Is it appropriate for non-black people to “celebrate” an event linked to slavery?

Jackson, who is mixed race, explains that Juneteenth is multifaceted and should mean different things to different communities. “As much as it’s something that I do want to celebrate, thinking about Juneteenth still does bring a lot of pain. It’s not necessarily just a happy holiday, because it’s a remembrance of the ways that black people are still not necessarily free – either free to be themselves in the world or free to be ourselves amongst family, stuff like that.”

It’s a time for us to really focus on, not even just the word celebration, but fellowship and kinship

Alyce Johnson, the senior adviser to the Vice President for HR on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), echoes this. MIT was one of a rake of US universities that have recently made Juneteenth a staff holiday. Johnson says that the events organised by the college for the holiday take on a range of tones and goals. Several, she says, are based on “educating people about [Juneteenth] and the significance of it”.

“We’ve been looking at our holidays for years”, she explains. “One of the things that I was involved in a few years ago was changing Columbus Day to Indigenous People’s Day. So thinking about: how do we send the message built into our systems, the message of value [and] acknowledgement of all people that celebrate the American history?”

“We have a holiday for July 4th, we have Veterans’ Day, we have Memorial Day, and all of these come with some history.”

Blanck, who is writing a book tracing the recognition of Juneteenth from its origins in Texas to the present day, believes that this year, the first year of a nationwide Juneteenth holiday, will be something of a litmus test for how the day is marked in the future. “When it’s coming out of the black community, having it be a celebration of freedom, of sort of encouraging empowerment, a lot of stuff with, like, small black businesses and things like that, because it’s a very local celebration, it seems appropriate. But when white folks are doing it, I think it needs to be more of a moment of reflection.”

How do we send the message built into our systems, the message of value [and] acknowledgement of all people that celebrate the American history?

“We saw that [become] a much stronger theme last year, that it was much more about reflection on black history, and understanding how far we have and have not come in the last 150 years.”

Blanck has also observed how state governments – from liberal areas like New Jersey to dyed-in-the-wool conservative Republican states – react to the holiday. The scope for inappropriately politicising the day is also something to note, she says. “Recognising a holiday is not doing very much about affirming the actual experience of black people, as opposed to like police reform or actual curricular reform in the schools. They [state governments] can just say: ‘Look, we added Juneteenth! Hurrah!’”

Even the date on which Juneteenth is celebrated calls into question the role of the government: the Emancipation Proclamation was signed in January 1863, but the Union Army did not arrive in Texas to enforce emancipation until June 1865.

Blanck explains: “That story sort of brings with it the sense that it’s there’s celebration and happiness at the fact that they’re emancipated, but at the same time, there’s this understanding that you can’t really depend on the government, you can’t really depend on others to really bring your emancipation on time.”

Jackson also ponders the possibility that the federal government will go no further than simply recognising the holiday. “That’s very representational and very far removed from the majority of the people, who are black, living in America [and] are not federal employees. Juneteenth will not bring any type of break for them. There’s people who are either caregivers or involved in informal economies who are totally left out.”

Johnson, musing on her personal experience, strikes an optimistic tone.

“I can remember, going back almost 20 years, there’s always been a Juneteenth celebration in my black community”, Johnson says. “And it was recognised by families and family reunions, and people coming together and community. People that, let’s say, moved away years ago would come back on this particular day.”

“For me, as an African American woman, seeing an organisation that I’ve been with for 30 years, really shifting and growing and becoming much more inclusive – I’m very excited about [that]”, she adds. “I do hope that it will spread along.”