Having landed in South Africa less than 48 hours after the British and Irish Lions’ 27-09 defeat by the Springboks back in August, the “deep end” of South African sport was something with which I became – or rather, was forced to become – very quickly. The intensity with which my Lion-orientated partiality was greeted – intensity measured in both hostility of stare and in unambiguity of abuse – was in no way underwhelming.

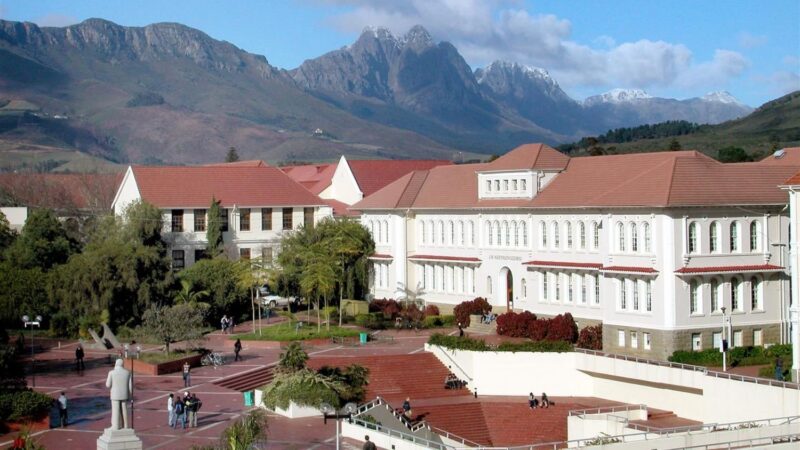

They like their sport in South Africa. They really like their rugby. Whilst many foreigners know this, fewer experience it firsthand. From what I can gather from my first two months studying here at Stellenbosch University, the nation’s uncompromising passion for sport – and all accompanying flaws – are well encapsulated in the sporting landscape at South Africa’s oldest tertiary institution.

Thus began my quest to assimilate myself – as best as one can bear the burdensome dual crosses of a painfully English accent and the frame of a beanstalk – amidst the rich sporting heritage on offer here. The sheer range of sports offered is immense. With a campus surrounded by beautiful blue mountains, and with the Cape Town seafront a mere half hour away, the sporting potential afforded by the geography engulfing Stellenbosch is sizable. Mountain biking, kitesurfing, windsurfing and canoeing are all easily available to students. With such variety so accessible, you would be forgiven for thinking that the potential for successfully immersing myself in this sporting haven, purely from a probability perspective, was rife. Armed with a distinct lack of coordination and a knack of consistently miscommunicating, I set about disproving the laws of probability.

First to be butchered were “parasports”. Having already encountered several extreme sports listed above it on the university website (mountain biking etc), I assumed parasports to entail a continuation of this extreme theme – paragliding, perhaps wingsuit flying, the occasional bungee jump. Buoyed by the idea that looking like an idiot would, for once, not be a trait confined to me in these sports, I eagerly emailed the lady in charge to express my keen interest. “I am without any health impediments or injuries” and “I am inexperienced yet fit and mobile” are but two extracts from our (ultimately one-sided) correspondence. It was only when lamenting the absence of a response to an initially sympathetic friend a week later, that I was duly alerted to a possible explanation for this dead end. Namely, how stressing my mobility to a lady who oversaw the university’s wheelchair rugby, wheelchair football and para-swimming programmes might fail to elicit a response.

I did realise that “cheerleading” was not a viable option for a man who has been repeatedly been nigh-on evicted from a number of the region’s bars for his zealous distribution of shapes

Not to be deterred, a further perusal of the sports website briefly brought “underwater sports” to the attention of both my retina and imagination. However – perhaps due to scarring from my previous misinterpretation of a novel sport, or perhaps due to the fact that my short-lived yet trauma-bathed swimming career could itself be aptly described as an inadvertently “underwater sport” – it was a prospect whose allure evaporated somewhat rapidly. Another red herring was my sojourn in a canoe: this particular venture drew, in the minds (and then colourful feedback) of some of the baffled onlookers, parallels to the scenes from their baths that morning. However, I was not totally naive, knowing as I did that “cheerleading” was not a viable option for a man who has been repeatedly been nigh-on evicted from a number of the region’s bars for his zealous distribution of shapes. Still, with golf, kitesurfing, windsurfing, gymnastics, water polo, equestrian and tug of war (to name but a few) all untried, hope was not lost.

It is also worth noting that the prestige of the clubs on offer here should in no way be detracted from by the ineptitude of my attempts to join their ranks. As the primary recipient of the university’s attention and funding, it is rugby which, like Trinity, exhibits this prowess most lucidly. Unfortunately, the standard male diet here (steak for breakfast, lunch, and dinner – all complemented with multiple jugs of protein powder in between) has largely precluded me (on chiropractic grounds) from reigniting an already extremely average rugby career. However, as alluded to earlier, one need not play the game to be in awe of its magnitude in these parts. The university’s Danie Craven Stadium seats over 17,000 spectators, and there are 53 teams with more than 1300 registered rugby players participating in league matches. These are numbers whose equivalent one would struggle to locate anywhere in the world. Stellenbosch has also produced 180 Springboks and 15 Springbok captains, and usually has around 15 players each year playing for provincial professional side the Stormers – alongside the likes of current Springbok captain Siya Kholisi and star lock Eben Etzebeth. In addition to all this, the Springboks also regularly use the university’s facilities to train – as they did in the build-up to the first Lions test this summer (or winter).

Nor is this international presence confined to rugby. In the build-up to the 2012 London Olympics, over 260 competing athletes trained at Stellenbosch to take advantage of the world-class facilities and warm climate. Many of the university’s athletes themselves are also Olympians. Thirteen represented the university team (four of whom comprised the national Water Polo team), as well as three coaches. Seven para-athletes – whose ranks I so erroneously threatened to join – also represented the university on the world stage. Whilst I back myself in the pace department – velocity possession which anyone who has witnessed me nail a blackcurrant-infused Guinness will surely testify to – I could not help feeling that my input to the Stellenbosch athletics scene may be deemed surplus by some.

The prestige of the clubs on offer here should in no way be detracted from by the ineptitude of my attempts to join their ranks

One final dimension to the student sports scene that I have encountered here – one which probably bears a broader national significance than my hitherto failed sporting quest – is that of race. The university’s rugby teams are predominantly white, as are the various aquatics teams. In a country where over 90 per cent of the population is not white – and a university where over 40 per cent of students are not white – this does not seem right. The explanation behind this is, of course, multi-faceted and too broad to investigate in any depth with the remainder of this article. Nonetheless, decidedly more succinct is the feeling that given the proximity of apartheid – the national laws sanctioning racial segregation and discrimination against non-whites only ended in 1994 – it would surely be naive to suggest that the idyllic bubble sealing Stellenbosch is not without systemic flaws. And yet the fact that the majority of the football team is not white is another fact which only convolutes the picture further. Clearly, additional observation and analysis from my already familiar position on the touchlines would not be unwarranted before any decisive conclusions are formed.

Whilst my blundering attempt to find a niche amidst the student sport scene here at Stellenbosch reflects nothing but my total incompetence, the university’s own sporting complexion appears to reflect something rather more profound. “Our club”, notes the university’s Sport Chief Director Ilhaam Groenewald, “is a microcosm for what is happening in South Africa”. From what this punter has witnessed – aside from interminable rejection – during his first two months here, her assessment certainly resonates.