Located not far from the banks of the River Foyle in Derry city, the slowly expanding Magee university campus is a key presence in access to higher education for those in the north west. The central red brick facade of the main entrance harks back to the Victorian era and highlights a past chequered by lack of investment and controversy that heralded in the beginnings of the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland.

Garbhán Downey, a spokesperson for the Derry University Group, recalls in an email statement to The University Times that “the campaign for a Derry university effectively began in 1960, when the issue was first raised by two city MPs, Edward Jones, Unionist, and Eddie McAteer, Nationalist, at Stormont. The men proposed the North’s putative second university should be located in Derry. Initially, the move had no opposition.”

However, in February 1965, protests began to develop following the conclusion of the Hooper Report, an investigation into the provisions for higher education in Northern Ireland. The report controversially recommended that a second university should be located in the majority Protestant town of Coleraine. Large-scale protests emerged in the wake of the report’s conclusions. The Mayor of Derry and Ulster Unionist Party politician, Albert Anderson, and leader of the Nationalist party, Eddie McAteer, noted how the issue had united both communities in the city. They subsequently led a convoy of over 1,500 cars to the government buildings at Stormont in protest at the report’s recommendations.

In spite of such prominent protests, the government followed through on the report’s recommendations and the new Ulster University campus was established in Coleraine. Describing the events, SDLP MLA Sinead McLoughlin states: “It was a body blow for the second city in Northern Ireland that the university wasn’t placed here, particularly when we had the Magee campus already established in the city.”

The Magee college was later merged into Ulster University in 1969. Such historic and long-standing political discourse for the higher education sector in the city is compounded by the poverty rates and lack of opportunities for many who call Derry city home. The Derry and Strabane council area has the highest poverty rate in Northern Ireland, furthering the case for investment in the area.

While many acknowledge that investment in the higher education provisions in the city is essential, there are a variety of opinions regarding how this can be achieved. The Derry University Group has put forward the proposal of a new cross-border university situated in Derry city. In 2018, the group met with the Oireachtas to put forward the initiative. Since then, it has been supported in both British and Irish governmental papers.

Downey highlights the belief of the Derry University group that “a new university would kickstart the North West’s dormant economy and help regenerate and provide a new sense of purpose to the region.”

Colm Burke, a Fine Gael TD for Cork West, has also put forward his support for the introduction of a new university in the city. Drawing comparisons between Cork and Derry, he underlined the role of higher education in helping to develop the city’s economy and skilled labour: “I reckon we have about 25,000 students between Munster Technological University (MTU) and UCC … And there’s a huge spin-off for the local economy when you have a university or when you have a third level college then that in turn attracts business.”

Burke has previously proposed naming a second university in Derry the John Hume Memorial University, citing the global acclaim that the late SDLP leader’s name brings. “The name has international recognition. I reckon if you did something like that, you probably would attract investment from America in particular, where there’s a huge large community, which had a huge loyalty to him.”

For local representative McLoughlin, among her biggest concerns is providing opportunities in the northwest for young people to study. She notes: “Our greatest export has been our young people… because of the lack of actual provision of higher education places our young people have chosen to go to Liverpool, to Manchester, my kids went to Glasgow and Edinburgh.”

Approximately 17,000 students from Northern Ireland attend university in England, Scotland or Wales. However, McLoughlin points out that the expansion of higher education in the north west shouldn’t act as a deterrent for those wishing to study outside the region, but rather as a measure to ensure that young people have third-level courses available to them at home.

Our greatest export has been our young people, because of the lack of actual provision of higher education place

“Daughters and sons are in effect forced to move away from their families because of the shortage of university places and the limited choice in courses locally”, she stated before adding: “I can understand that young adults want to move away from the family home to expand their life experience, but they should not be forced to do so. Ireland has had too much forced emigration.”

Indeed, Burke also raises his concerns with the lack of university places available in Northern Ireland as a whole, noting that the region suffers from “a huge deficiency in university places”.

Situated right alongside the border, Derry city unsurprisingly sees a large number of cross-border workers, and such movement of people draws attention to the role of cross-border links. Downey emphasises the role of increased cross-border cooperation, noting that: “Particularly post-Brexit, we need to be imagining new ways of sharing this island and new North-South partnerships that will allow our communities to share resources, skills, and learning as expeditiously as possible.”

Speaking to The University Times, Sinn Féin councillor for Foyle Conor Heaney highlighted examples of where such links are already underway. Heaney drew attention to the efforts that have been made to foster a relationship between Ulster University Magee and Letterkenny IT which “have been building steadily over the past while”. Indeed, the geographic location of Derry city automatically lends itself towards increasing cross-border relations. This was illustrated upon the opening of the Magee medical school which operates on a cross-border basis.

The opening of the medical school was a key aim for many third-level stakeholders. Heaney outlined its significance for the region: “The recent opening of the medical school at Magee creates a medical school for the entire north west of Ireland, from Sligo right up to Derry. This was done in order to try and start creating doctors and nurses from this region, who will stay in this region and will service all of the medical facilities in the area.”

McLoughlin also underlined the importance of establishing such facilities and university courses in Derry. “Clearly the medical school is important, not least because of our local shortage of GPs, but it also needs to expand.”

The recent opening of the medical school at Magee creates a medical school for the entire north west of Ireland, in order to try and start creating doctors and nurses from this region, who will stay in this region

Indeed, the enlargement of the Magee campus generates questions about the emergence of another university in the city. In 2020, the New Decade, New Approach Agreement – which reinstated Stormont after a three-year absence – contained a clause that aimed to achieve student numbers of 10,000 in third-level education in Derry city. Such a goal has resulted in a variety of conversations about the expansion of Magee.

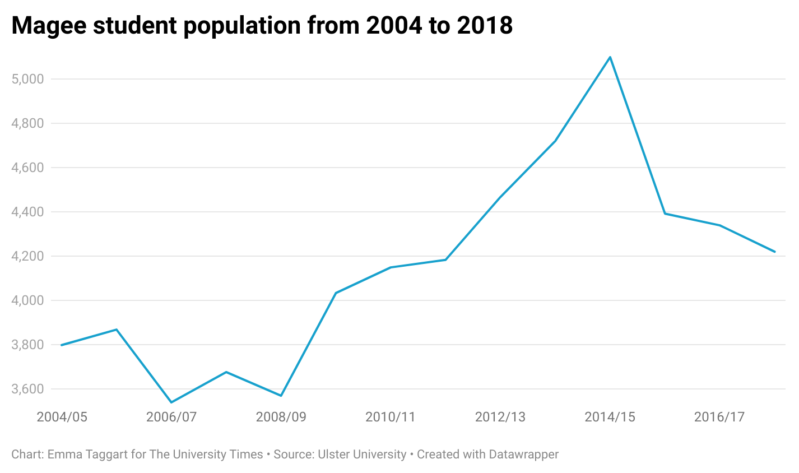

“We have over 5,000 students at Magee and that has been steadily expanding. We need to have a time frame and a clear roadmap to take that up to the 10,000 figure that is our target and indeed beyond that”, Heaney states, before noting the key role that the medical school has played in the recent expansion of Magee.

In a similar vein, McLoughlin highlights the role of degree specialisms in aiding the expansion of Magee alongside increasing opportunities. “We have some important specialisms coming to Magee, which can be the basis of a stronger economy, generating higher incomes into the city and region”, she said.

While talk of figures, expansion and economic growth may seem tangential to those not from the region, discussions about higher education in Derry have a long and deeply political history, as Heaney underlines. “This has been a topic of hot political debate here for years now. We’ve been trying to expand the Magee University. It has been a 50-year campaign.”

Irrespective of whether plans for a new university go on to become a reality, it’s clear that there is a deep-seated need for investment in the higher education sector in the north-west, as McLoughlin points out: “The North West has skills shortages which would be addressed by an expansion in university provision. Several local employers have called for more student places. For example in relation to software development, engineering and renewable energy.”

She goes on to highlight that the need for investment in higher education and the goal of reaching 10,000 students in Derry is of greater importance than the higher education institution that they study in, so long as it is located in the north west. “I don’t care what type of university it is or who owns the university or what the university is called or if it’s even called a university at all. I want to see higher education, places, and students stay here in whatever body that is.” She adds that the target of 10,000 students is “unambitious” and highlights the disparity between provisions for higher education in the north-west in comparison to Belfast.

It was a body blow for Derry, the second city in Northern Ireland, that the university wasn’t placed here

Heany reiterates McLoughlins point, stating that “there’s obviously been a bias in our view, towards Belfast for quite some time … and we’re trying to rebalance that and build places in the north west.”

Unfortunately, the future of higher education in Northern Ireland looks set to remain uncertain, with a recent report from the Department of Economy which has modelled decreasing university places and raising tuition fees by nearly 60% in order to save money. As a result, key concerns about what’s to come for the higher education sector in Derry remain, but at the heart of it is addressing a skills gap that exists in the region. McLoughlin summarised the issue succinctly, stating: “We have too many school leavers who do not have the skills required in the modern economy and to provide good careers for those pupils. Addressing that is just as important as university expansion.”