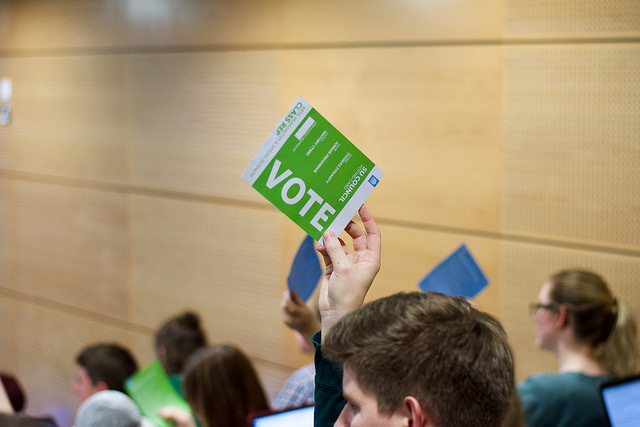

In 2018, by a slim majority, Trinity students voted against a constitutional amendment that would allow members to opt out of Trinity College Dublin Students’ Union (TCDSU).

Fast forward a few years later and TCDSU’s constitutional review working group proposes a student-wide referendum on the right to opt out. The question at the core of the mandatory/voluntary student union debate, however, is as old as student unions themselves.

It all comes down to what role student unions should play. Are they bodies whose main purpose is the provision of student services? Are they forums through which student voice and student activism are channelled? Are they both?

Historically, TCDSU has not shied away from taking harsh stances on divisive political matters. From abortion rights to the Israel-Palestine conflict, the union isn’t afraid to take a stance on issues not everyone will agree upon. For those who don’t concur with the union’s stance on a given topic, the right to opt out offers them the ability to distance themselves.

The vast majority of students are just going to be indifferent to this. For those that really care, the answer is simple: Let them leave

“[It] really stands as just a symbolism thing”, Daniel O’Reilly, an erstwhile member of TCDSU’s constitutional review working group, tells me. He explains that, when it comes to TCDSU, “the vast majority of students are just going to be indifferent” and, for those that “really care”, the answer is simple: “Let them leave.”

Inspired by the legal framework used across the UK, O’Reilly stresses that the opt-out model was the only one that the constitutional review working group seriously considered. Nevertheless, he admits that when the issue came up in 2018, he had “fervently argued against [it]”.

He explains: “I had this fear of people denying themselves services and the SU having to get caught up in this ‘who’s allowed SU services and who’s not allowed SU services?’”

However, under the model proposed by the working group, all students are entitled to access TCDSU services, whether they are a member of the union or not.

Having established that there are “no real logistical challenges” to implementing a right to disassociate, O’Reilly indicates that the decision to include it in the draft was simple: “If there’s no downside to giving someone a right, why wouldn’t you give them that right?”

The opt-out model proposed by the constitutional review working group contrasts with the opt-in model that is used in Australia and New Zealand. In both countries, student union membership is completely voluntary and has been since 2006 and 2011 respectively. However, the introduction of what is known as voluntary student unionism (VSU) in Australia and voluntary student membership (VSM) in New Zealand has been unpopular.

“The idea of VSM in New Zealand, certainly [in] Australia, was to cripple student unionism”, Andrew Lessells, the national president of the New Zealand Union of Student Associations, tells me.

The idea of voluntary student unions in New Zealand, certainly in Australia, was to cripple student unionism

At first glance, the opt-in model seems a world away from what is being proposed by the constitutional review working group. However, in reality, the reasoning behind both of them is not dissimilar. Lessells explains that a key argument in favour of the introduction of VSM was “that students should have a directly accountable association that they’re not forced to join”.

This is not unlike the reasoning behind TCDSU’s proposed constitutional reform. When asked what the motivation behind its inclusion was, O’Reilly tells me that “if you fundamentally disagree with the SU and … if it is hurtful to you to continue to be associated with this body”, you ought to have a right to disassociate.

Lessells does concur that “the idea of VSM is, in its own right, not an entirely horrendous idea”. The issue is that, in Australia and New Zealand, “it was always brought about as a means to disempower the voices of students and to crush student activism and crush the mandate [that] the students had for representation”.

Its introduction presented a real challenge to student unions, and “it did require us to become more representative. It did require us to really prove to students why we deserve to exist”.

For all the similarities that can be drawn between the system down under and ours in Ireland, stark differences continue to exist.

If you fundamentally disagree with the union – if it is hurtful to you to continue to be associated with this body – you ought to have a right to disassociate

Georgie Beatty, the president of the Australian National Union of Students (NUS) which represents over one million students, tells me that it is common for NUS to take official stances when it comes to national politics – in particular, elections.

“The official stance of the NUS going into the 2021/2022 campaign will be ‘put libs last’”, she says. Indeed, she admits: “We push their buttons a little bit … the Education Minister won’t meet with us.”

Although such stances are less familiar to TCDSU, there is common ground to be found in the reasoning behind them: “I’m not saying no to libs, I’m saying – this going to sound really poxy – but, yes to students”, Beatty says.

However, saying yes to students has become increasingly challenging in Australia following the introduction of an opt-in student union model. There is a clear contrast to be found in the way in which student unions there and in New Zealand receive funding and how TCDSU is funded.

Beatty tells me that while there is acceptance that the role of student unions is to scrutinise the universities they are attached to, the fact that they may be biting the hand that feeds them “definitely plays in a lot of minds of presidents when they’re negotiating”. She admits that she even consulted her university’s student union president before speaking to me to establish “the level that I can kind of go to in criticising [it]…I don’t want to fuck up their negotiations”.

While there is acceptance that the role of student unions is to scrutinise the universities they are attached to, the fact that they may be biting the hand that feeds them definitely plays in a lot of minds of presidents when they’re negotiating

Similarly, in New Zealand, this is a difficult line to draw. Lessells tells me that recently, in the midst of contractual negotiations, several of his colleagues were approached by senior leaders from their institutions and advised against making a submission on an upcoming parliamentary bill. He tells me that they would “come to them and effectively say: ‘If you do, those contract negotiations might not go particularly well’… we are effectively seeing blackmail”.

The impact that this has on student unions is devastating because, as many may suspect and as Lessells confirms, they quickly begin to self-censor: “They just don’t criticise in the way that they could do once upon a time.”

Despite the challenges that the opt-in model has posed, O’Reilly is confident that student unions who operate under an opt-out model would not suffer the same fate. In fact, he believes that optional membership may strengthen the power of TCDSU when it comes to taking political stances. He tells me that, while he believes that the number of people “who disagree so heavily with the SU” that they would disassociate would be “quite small”, even if “the SU lost 20 per cent of the membership, it goes back to well, was it right for the SU to claim the support of that 20 per cent?”

TCDSU should not, he feels, be “basing its political power on, we’ll say, misrepresenting that group”. In this sense, the opt-out model could make TCDSU’s stances stronger because it would enable it to authoritatively say how many students it has behind it.

Indeed, the fear of misrepresenting students cuts to the core of why O’Reilly and others fought to introduce the right to disassociate. He tells me that “it seemed ethically dubious that this system was built on no one being able to afford to challenge it. If it was financially viable, there was plenty of people who probably would have been interested in suing to try and challenge this rule.”

The opt-out model could make TCDSU’s stances stronger because it would enable it to authoritatively say how many students it has behind it

Although a challenge to the constitutionality of mandatory student unionism is unlikely to see the light of day, O’Reilly tells me that, “consensus was if it had gone to the courts”, it likely would have succeeded.

“It sort of comes down to what is the SU there to do? Is there to be a radical activist group or is it there to be a support union and provide services for members?”, O’Reilly asks.

In New Zealand, it seems that the two could not co-exist and that, as Lessells explains, the introduction of the opt-in model “[led] to a real transition away from student voice and student activism towards services”.

For O’Reilly, this is unlikely to be an issue: “[TCDSU’s] primary purpose should be [the] provision of services, to support members.”

While some may worry that this is the end of TCDSU’s long legacy of student activism, O’Reilly does not seem overly concerned: “My core philosophy with the opt-out membership is that it’s really not a big deal.”

CorrectionL 6:40pm, March 2nd, 2022

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that a proposed new TCDSU constitution includes the right to disassociate from the union. In fact, the Constitutional Review Working Group proposed that the right to disassociate be put to an individual, student-wide vote.