Prehistoric fish currently roam Ireland’s frigid waters, and there’s been a great effort to ensure the fish remain there. On October 2nd of this year, the basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) became the first marine animal protected under the 1976 Wildlife Act. The second-largest living fish is now a “protected wild animal”, meaning it is illegal to hunt, injure or interfere with the threatened species. To find out more about the deep blue sea (which, as it turns out, is relatively shallow at only 50 metres deep around Ireland), The University Times sat down with Haley Dolton, a PhD student at Trinity researching these sharks.

Dolton explains that at 12 metres in length, the basking sharks’ primaeval appearance and grandeur lend themselves to a myriad of questions, including how they function and move, what alters their behaviour and where they go. Their size is also advantageous for research as it allows scientists to deploy developing technologies on the sharks before they undergo refinement and miniaturisation for the smaller species. This line of questioning led Dolton to her PhD project, intriguingly named “Ecology and Biology of Ireland’s Giant Fish”.

To better understand the basking sharks’ ecology, physiology and biology, Dolton worked on the Isle of Man for several years using histology and biologging, the latter a method of studying animals in their environment by harmlessly attaching tracking devices to them. Dalton intends for her work to inform effective conservation planning because, as she aptly describes, “without knowing about your species, it’s very hard to effectively conserve them”.

According to the Heritage Foundation, Irish waters are home to 39 species of sharks residing in various habitats. This means that “it doesn’t matter where you are in Ireland, there’s probably a shark nearby”. If one is along the west coast, they are more likely to run into a basking shark. The major threats they currently face are the consequences of climate change, accidental bycatch in fishing or pipelines and human disturbance.

Their size is also advantageous for research as it allows scientists to deploy developing technologies on the sharks before they undergo refinement and miniaturisation for the smaller species

Dolton wishes to remind everyone that “when interacting with wildlife, you need to remember that these are wild animals, and you should be showing them a lot of respect and admiration. Just because you want that selfie doesn’t mean you have any right to do so, as amazing as it is to see wildlife. See it from their terms. So, if they want to approach you, great. If they don’t, don’t force it”.

It is a very exciting time to be a marine biologist in Ireland. The 2020 Programme for Government delineated an expansion of Ireland’s marine protected areas (MAPs) to 10 per cent of its maritime area “as soon as is practical” and declared a commitment to protect 30 per cent of Irish waters by 2030. The legislation will establish these areas as protected spaces for marine life, effectively providing a firm legal basis to hold offenders accountable.

The MAP’s protection of ecosystems and resilient marine life benefits not only the underwater population but also the economy, fisheries, tourism, cultural traditions and many other aspects of society. In addition, the Minister of State Malcolm Noonan commented that within “the context of energy security and the ramping up of Ireland’s offshore renewable energy ambitions, it’s all the more important that we work at pace to deliver on our commitment to meeting both biodiversity and climate objectives”.

In August of this year, the government approved the development of a scheme of the bill, and implementation is soon to come. Dolton believes that “this positive marine conservation push that’s going on at the minute” is an exciting driving force for the future of marine biology.

Without knowing about your species, it’s very hard to effectively conserve them

Dr Nicholas Payne supervises Dolton’s PhD project and is the head of The Payne Lab – a group of marine biologists based in the School of Natural Sciences at Trinity. Lab members research a broad range of themes in the field of marine biology, which includes a fascinating study into thermal biology: “[the] lab uses a wide range of approaches – from bio-logging with wild animals to laboratory experimentation and theoretical modelling – to explore how temperature regulates the individual performance of animals, and how that relationship then sets limits to the environments they can inhabit in nature.”

Additionally, lab members are studying ecotourism and the industry’s effects on the behaviour and health of marine life. Their research provides captivating insights into humanity’s impacts on the oceans from a variety of analytical angles unique to their studies.

For non-marine biologists looking to support the conservation effort, Dolton recommends looking into citizens’ science projects, including the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group, the Irish Basking Shark Group and other local wildlife trusts. These programmes offer training for anyone interested in engaging with local wildlife.

Dolton also emphasises the value of reporting your sightings in Irish waters as that can be incredibly helpful for research. For aspiring marine biologists, Dolton suggests openness to all available opportunities for hands-on experience rather than stressing a linear path toward one’s career. As she studied other areas of biology throughout her education, Dolton advises gaining skills from a variety of disciplines because the marine biology field continues to advance, and exciting developments are on the horizon.

Just because you want that selfie doesn’t mean you have any right to do so

As Ireland is an island, we rely greatly on the seas and the ocean, and we are collectively responsible for caring for them and their inhabitants in turn. Be vigilant and respectful of your surroundings along the coasts, and remember: a selfie with an aquatic relic sounds cool in theory, but it’s better to be dazzled from a safe distance, for you and them both.

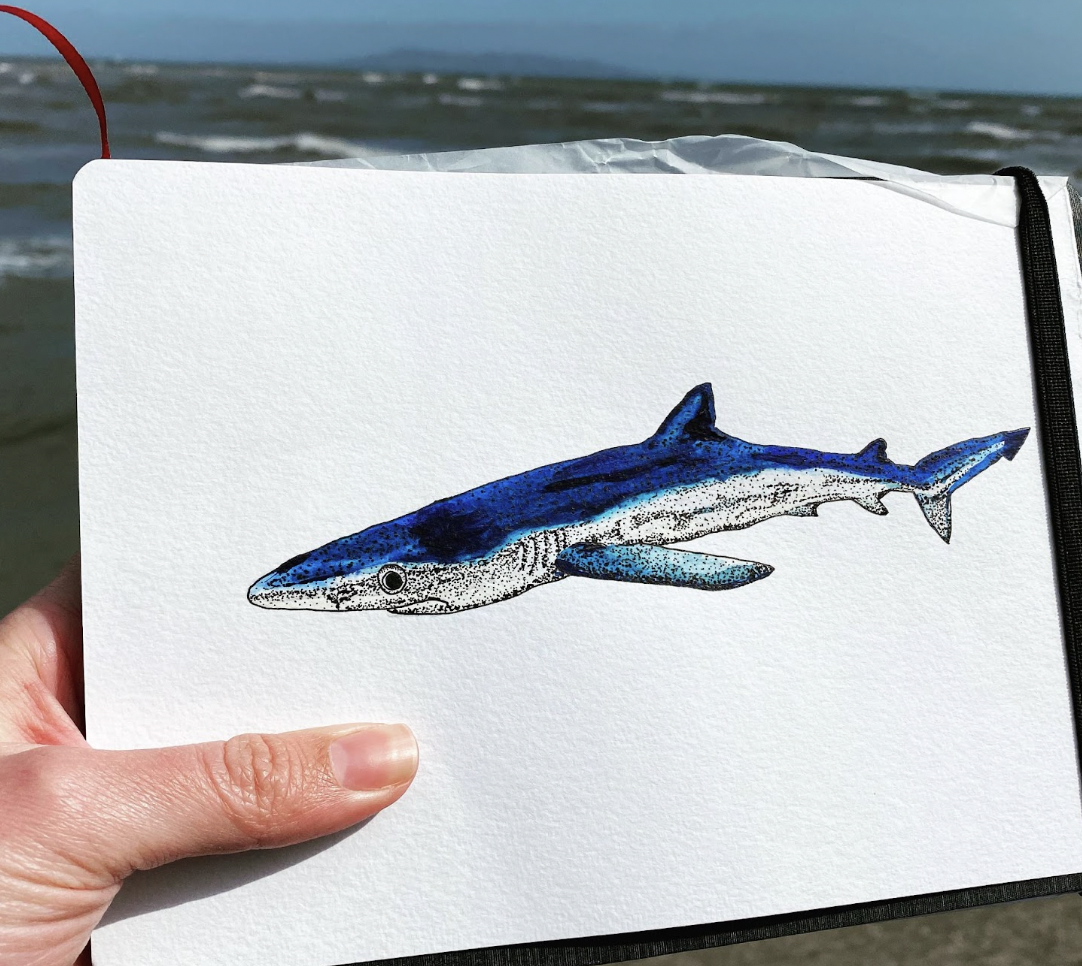

Dolton draws inspiration for her incredible artwork from her encounters with Ireland’s marine life. To see more of her artwork and other work, visit hayleydolton.com.