“It took a century…” reads three statements in Room 21 of the National Gallery of Ireland, a prominent room usually used to display Irish art from the late 17th to early 19th century. Now, though, the room is filled with 59 works, from all the women who have been members of the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) during its 200 year history. If 59 seems like a small number, that’s because it is.

When the RHA was given a royal charter in 1823, artists had already been pushing for a space such as it for years. The mission was to create a permanent space for artists to work, learn and display art in Dublin. They also sought to establish Dublin as a prominent city in the European art world.

Throughout the turbulent 20th century, the RHA managed to find a foothold in this new society. However, they retained a reputation for conservatism and remained exclusionary towards women. It wasn’t until 1924 that Sarah Purser became the first full female academician, five years after women were granted suffrage.

Despite Purser’s election, women still did not enjoy equality. Despite their qualifications and high rates of enrolment in RHA schools, very few women were elected to be members until recently. The current president, Dr. Abigail O’Brien, was elected in 2018 and was the first female president of the RHA.

Upon entering Room 21, it becomes very clear just how rocky the path was to equality. A piece by Aideen Barry catches the eye straight away, not because of what it shows, but because of what it doesn’t. On a blank canvas next to the door, she states in small font that she is declining to participate due to a contract the NGI has with a catering company that “profits from direct provision – a system [Barry] believes to be inhumane and undignified”. Her statement sends a message, and it speaks to the issues related and unrelated that this exhibit fails to address. However, the overall feeling of the exhibit is not of protest, but of community.

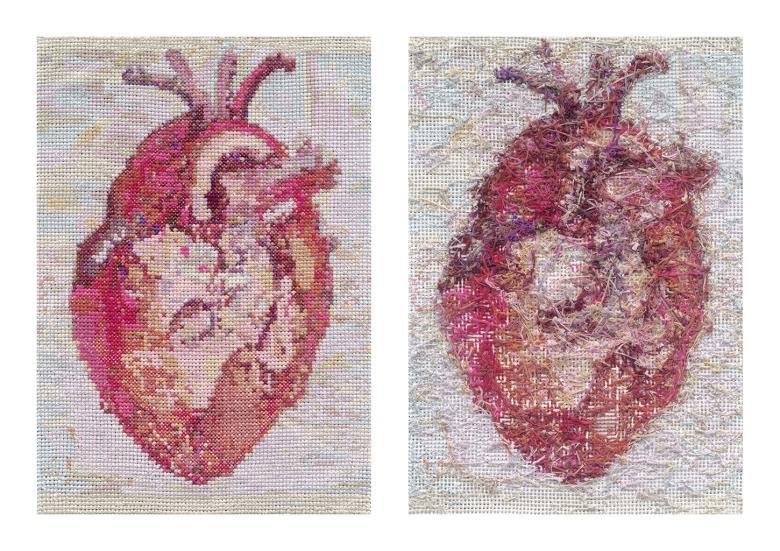

Hanging next to Barry’s piece are two large canvases entitled “Perfection I and Perfection II”, by Abigail O’Brien. On one canvas is a large heart, embroidered perfectly. On the other canvas is the same heart, but the flip side. There are loose strings hanging down in places, and without its match hanging next to it one would think it forms no picture. But in O’Brien’s title, “Perfection II”, the viewer can match one to the other, and see the beauty in the perfect chaos.

Moving into the first alcove, Amelia Stein’s portrait of Barbara Warren, another RHA member, hangs unassumingly. Stein points out her favourite detail of the photograph, a slip of a floral sleeve beneath Warren’s paint-splattered tunic, a personal touch. It’s these details that give Stein’s photograph life, despite being black and white. Through Stein’s account of their meeting at the time of the photograph and the photo itself, I felt almost as if I was enveloped in the small pocket of time the photograph represented, bathed in the warmth and kindness Stein stated that Warren possessed. In the room neighbouring Stein’s photograph, a painting by Warren hangs. It’s a landscape, and Stein’s portrait allowed me to view Warren’s work through another, more personal light.

The exhibit represents a wide variety of artistic styles and genres. However, through their shared journey and history, it forms a cohesive community, and each artist is present in one another. Representing the bicentennial of the RHA, this exhibit highlights the issues the RHA still faces and while paying homage to its pioneering female academicians.

The exhibit is on display until October 22, in Room 21 of the National Gallery. Admission is free.