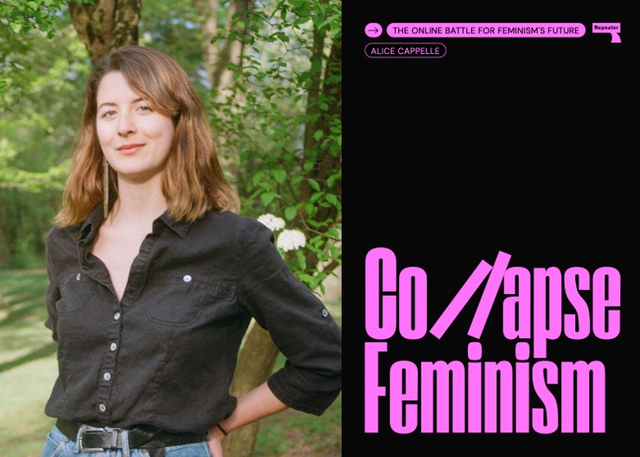

Alice Cappelle’s YouTube videos can go from a clip of an influencer’s daily routine to an in depth analysis of Foucault and Freud within the time it takes to skip an advert. The successful video essayist has now published her first book, Collapse Feminism, an attempt to rewrite the discourse that modernity is a descent into doom.

Cappelle doesn’t just criticise groups or trends she deems unjust, but analyses the ethos they are based on in order to consider an alternative. This makes for a wide-ranging, relevant and compelling book. It is a welcome change to read an insight into Internet politics from someone with an empirical knowledge of producing, as well as consuming, content. Cappelle’s background in academia also evidently informs the essays, ensuring that rigorous research underpins every anecdote.

The book is not particularly groundbreaking in its critique of archetypes such as the Girlboss, or the conclusion that we should put our hope in supporting and educating the younger generation. However, Cappelle’s ability to contextualise modern feminist issues with clear explanations of helpful academic theories makes Collapse Feminism a useful guide to thinking critically about the trends, tropes and movements that dominate discourse.

Cappelle will be hosting an event at The Winding Stair to promote Collapse Feminism on November 29th.

Interview has been edited for concision and clarity.

In your definition of“collapse feminism”, you say that it “seeks inspiration from people at the margins who refuse to settle for fatalism precisely because their existence depends on believing that things can get better.” How do you balance criticising society and being aware of injustice with optimism and a hopeful outlook?

When I was starting to do the research around the book, this concept of ‘collapse’ very quickly came to mind. I was looking at books, essays and articles, and it often felt like criticisms that were not being resolved. I thought “I don’t want to do that”. I don’t want to just criticise, I also want to bring something positive, even if it feels like we’re the last, or lost, generation. There are people out there who have to want to experience something positive because their existence depends on it. That’s where I tried to seek inspiration and what I really focused on. I’ve seen more and more activists saying “can we also celebrate and see all the fights we have achieved”? That’s what I wanted to get across in this book.

Your background is in video essays on YouTube as well as academia. Did those different forms work well together when writing the book or did you find that they conflicted?

I definitely thought about that when I was thinking about how I wanted to structure the book. I thought: so am I going to do a very strong thesis that is going to be coherent throughout the whole thing or do I try to do something that is more coherent with what I do on YouTube (a ten to twenty minute video on a given topic, usually related to an internet trend). So I kind of tried to do both – to have a thesis throughout the book but also explore different niches. [With Collapse Feminism] I wanted the same experience as when you’re on social media and you can decide to hop on a trend or a niche or a community and explore it. And then I also tried to connect that and come up with a stronger thesis. When I left academia, I debated whether I should do a PhD or not. I decided not to because I wanted to explore many different topics and bring everything I’d learned to those very niche areas. I guess there’s a little bit of both in this book. I wanted to back it up with some sources and academic works but at the same time I wanted to keep it entertaining and light-hearted in some parts. I mean, when you look at the subtitles of some sections they sound like, “is this serious?” But I still wanted to keep that entertaining vibe to it.

You talk throughout the book about the idea of “patriarchy’s culture of domination”. It seems to me that social media can also dominate through algorithms and the way it can control us slightly. I was wondering what you think about the Internet’s power to contradict but also reinforce this culture of domination?

We have this term, ‘the attention economy’, meaning that what works on social media is usually the most sensational, most outrageous type of content, which makes it very easy for extremist ideas to circulate. For example, I talk in the book about the manosphere, which is this group of various men that gather around sexism and misogyny. They’ll have the craziest titles under their videos. Even me, as a feminist, I’m tempted to click on those videos because they’re saying things that most people wouldn’t dare say. That’s something a lot of feminists have been saying recently – that sexism is raw now because of this clickbait element where it’s okay to be misogynistic because it brings views, it brings engagement. That’s something we need to work with as online feminists and social justice advocates because we value things like education, we value critical thinking, and unfortunately the structure of social media does not really help that. It’s a difficult task because it feels like we’re constantly fighting twice as hard as people who just put a clickbait title [under their video]. We’re fighting against that and the attention economy favours that.

I think that links in with the idea of putting out content online which reaches one audience and then writing a book which might also reach a new audience. Do you see the aim of the book as similar to your videos or is your goal with Collapse Feminism something else entirely?

I was happy when the publishing house reached out to me to write the book because I’ve always felt deep down that there are so many good things happening on social media (outside all the things that I’ve just talked about). There are a bunch of online analysts like myself who produce content and try to educate people. I’ve learned a lot as well. I’m always kind of frustrated to see that there is still a strong barrier between the worlds of academia, journalism, the literary world and the world of social media. We’re not taken as seriously despite the fact that there are videos that really change my perspective on very important topics. We don’t value [YouTube Creators] enough because we’re younger; we don’t talk like scholars. That is a strength for us, but some people will see it as a weakness because we’re not as legitimate. I guess one of the goals for this book was also to legitimise what is being talked about within that internet analysis. I hope it’s going to work, I hope I’m going to be able to reach out to a larger audience. Fingers crossed!

You talk about how intersectional feminism rests on community, and you consider friendship as potentially an act of resistance which should be promoted. How do you think this can be achieved?

I was inspired to write about friendship because of a French philosopher, de Lagasnerie. His desire to write about friendship started with COVID and the fact that during lockdown people in the same family could cross the entire country to see each other but friends on the other side of a street couldn’t cross the road to see each other. He didn’t like his family or want to spend any time with them, so he ended up being very alone. His proposition is to elevate friendships to the same level as family, which is a very bold claim and many people laughed at him when he said that. But, deep down it’s interesting to think about: what if friendship was, on an institutional level, considered the same way as family? And for many people that is the case. We tend to see this wonderful nuclear family ideal on TV adverts etc, but the reality is so much more complex. A bunch of my friends have families that are somehow dysfunctional, and friendship has always been a refuge for people at the margins, people whose identities do not fit with the environment they grew up in. So [we should] at least remove the stigma around friendship, the infantilisation of “they’re just friends”, compared to family which is more serious. There are various ideas of how to value that, but I feel like it’s important, especially with the loneliness epidemic. With the return of conservatism it’s also the return of the idea that we need to reinforce the family, but what about friendships? What about those who don’t dream of building the typical nuclear family?

In the conclusion to Collapse Feminism, you say that “we have failed to translate online movements like […] ‘quiet-quitting’ […] into an alternative to the work-domesticity binary imposed on women.” Do you think that online movements have the potential to instigate truly feminist change?

There’s nothing revolutionary about quiet-quitting and things like that, but I always find it interesting to still investigate those movements because I think it can at least plant a seed in someone’s head or help them reconsider something that they’ve been used to – working hard, putting a lot of time and energy into work. I guess the idea was to take movements that are quite popular online that don’t look revolutionary and see, if you take them out of this shiny trend, what we can do with it. If we really push them to the extreme, it can be a bit revolutionary. So I like to start with that, because if you just go to people and say “we’re going to abolish patriarchy” etc it doesn’t really resonate with people, or they’ll say “yes, but how do we actually do it?”

You talk about movements which prioritise the individual – like the trope of ‘that girl’ or the ‘girlboss’ – as being antithetical to intersectional feminism, which incorporates a “collective of difference”. Do you think the act of informing ourselves individually through books and videos such as yours can translate to activism?

On social media people enjoy when you are not too attached to reality. They like the idea that you are in a little bubble on the internet. I’ve noticed that whenever I make content that is more contextual and informative it doesn’t work as well – people prefer when I talk about ideas. It’s always a struggle to connect back to organisations or marches you can join. It’s definitely something that I’ve tried to do more. For example, I did a video on this trend called female rage, where people took clips of women displaying rage in movies, TV series etc and said “this is female rage”. I thought this was so interesting because rage is also something you experience when you go to a march or talk about those ideas with other people, so I knew that at the end I was going to be able to invite people to [take action]. But the conversation very much started with ideas and philosophy and sociology. So, I guess it depends on the topic and what people look for. I always see the work we do as part of a structure, where we talk about the bigger ideas and someone else or maybe a viewer is going to take something from it that will make sense in their own life. It has happened a few times where people tell me that they’ve seen my video and it’s inspired them to create something that is not necessarily revolutionary – but, still, they are taking something out of the video and creating something in real life. It’s so rewarding. But again, YouTube rewards being more abstract and YouTube is my job so I kind of have to take into account what people want.