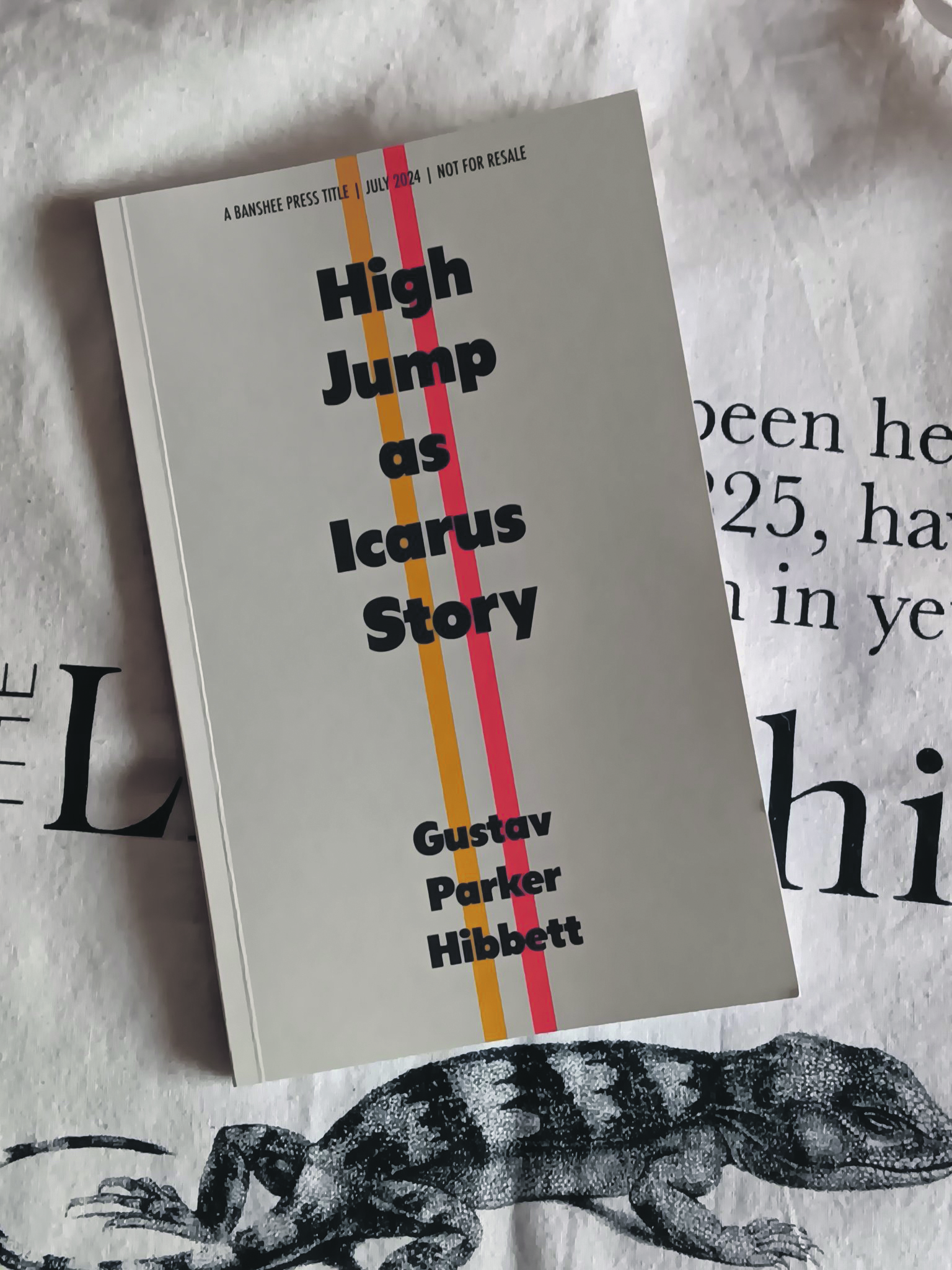

In late March, I sat down with Trinity student Gustav Parker Hibbett ahead of the release of their debut collection of poetry on July 4th of this year. Their talent was spotted by poetry editor, Jessica Traynor, after a submission to Issue 13 of Banshee. Traynor described the collection as a “stunningly accomplished debut [which] deconstructs and redefines notions of Blackness, queerness and masculinity through the lens of myth, pop culture and high jump”.

Having had the opportunity to read Hibbett’s collection ahead of its publication, I was struck by its gravity. Hibbett’s nexus is fluidity – race, gender, desire and the body are questioned with rigour. This corporeal sensitivity is not only underpinned by personal vulnerability, but equally by a sense of triumph and pride. In Hibbett’s work, there is no freezing of the flight, as we move with the poet through various epochs, (including, most prominently, classical Greece) landscapes, (including Alabama and West Cork) and positions (such as the Fosbury Flop and confinement).

Hibbett began as a Maths major at Stanford University before eventually switching to English in their final year. “I found my way to it late,” they admit. After a teacher pointed them in the direction of Maggie Nelson’s genre-defying Bluets and Claudia Rankine’s masterful Citizen: An American Lyric in quick succession, Hibbett was confronted by a conflicting sense of restriction: “I had it in my head that it wasn’t the kind of major that a person like me would or could do. As a scholarship student of colour, I felt that everyone else in a similar position was doing a STEM major and I had gotten the advice so much as an undergrad that ‘you’ve been given the golden ticket at Stanford so make it count’ or hearing that switching to English was a waste, that I wasn’t utilising the potential gift I’d gotten. Also, the whole diversity thing, the way it was framed was like ‘Black People in STEM! We want you and your body in STEM, we want to champion it there but everywhere else, not so much.’”

Bolstered by a determination to pursue the liberating feeling they found as an athlete practising high jump, Hibbett began studying for an MFA at the prestigious program offered by the University of Alabama: “I was so confined in every other area of my life and that influenced how I moved through space, how I thought about myself, how I talked about myself and how I composed my face but none of that was there in high jump. I could just flow in this way that was so beautiful and it just felt as though I was my best sort of self – it was almost a transcendence. And it was devastating to lose that, something that felt so organically mine, but I found it with English and writing.”

However, the MFA experience soon became plagued by a gendered and racialized toxicity such that “work outside of the white perspective was not engaged with in the same way” and Hibbett was left with the tormenting feeling that their “work wasn’t worth engaging with”. They began hiding pieces from the workshop as a means of protection. When this work was later accepted for publication, Hibbett made the courageous decision to drop out of the program.

During their two terms at the University of Oxford as an undergraduate, Hibbett became connected to a larger group of friends in Dublin and was drawn closer to the city by a burgeoning relationship. In the autumn of 2020, as the U.S. election loomed, they sent a Hail Mary application to Trinity in the hopes of being accepted as a PhD candidate. Trinity’s PhD offered a chance to engage with both critical and creative writing. On finding the balance between the two, Hibbett explained: “Well, a lot of my early essays were in that Maggie Nelson style of the braided balance between the academic and the personal. Then, in my second year [of the PhD] I got the advice to focus more on the memoir or life-writing aspects which I did for a while and now I’m bouncing back to the more critical. The mini research projects strengthen my writing.”

Central to their writing is an engagement with mythology, Hibbett manages to use it as both a common cultural reference and a space in which reclamation is possible. “We are in a moment,” they observe, “the past twenty years have seen a lot of reimagined myths in popular cultural channels. I think it’s definitely in the air. I also think reimaginings from people who may be outside the Greek classical tradition like queer and black communities are reclaiming them”. Hibbett acknowledged and articulated their respect for those who choose to reject myth “on the basis that it’s a presupposed universal coming down from the Enlightenment in the form of the white man” but for them, growing up in the States meant having access to this particular form of mythology. Hibbett aims, however, to use the authority myths possess to subvert this concept of the presupposed universal: “Icarus is black now! I think there is some power to be had in reclaiming that.”

High Jump as Icarus Story, Hibbett’s debut collection, leans into this reclamation of the Greek hero. However, I was drawn to Hibbett’s pointed attention to the mirror concept of monstrosity rather than heroism. Often portrayed as one-dimensional characters, monsters’ bodies have a large part to play in an audience’s perceptions of them. Monstrosity for Hibbett “has been this way of reaching for the figures that I can relate to within the myths that I grew up around”. Citing demonised figures such as Othello, Grendel and the Minotaur, they articulate the potential of adapting the monster: “Monstrosity allows us to write back against dehumanisation while also showing us what it means to be human. By extending the concept of humanity and challenging the split between human/animal, monstrosity allows us to inhabit these beings that are used narratively to hold the fears of people – which is quite a delicate thing.”

In their collection, Hibbett manipulates this delicacy to spellbindingly illuminate how the body functions as a cultural site of process and production. This attention initially arose from a deep discomfort: “For so long, I almost tried to absent my body. In high school, I felt I was there to be a mind and not a body. I put so much mental energy into not listening to my body.” The politicisation of their black and queer body has forced it into the public sphere as a spectacle. So when they discovered Joni Mitchell’s appropriation of black masculinity as a persona for entertainment purposes, Hibbett contemplated their own relationship to femininity and the responsibilities inherent in that identification. Two poems in the collection (‘Joni Mitchell dresses up as me’ (I) and (II)) explore the poet’s complicated relationship with an artist who had such a formative influence on them.

Hibbett already has an impressive publication history with poems appearing in The London Magazine, The Stinging Fly and Guernica, among others. With the release of High Jump as Icarus Story, Hibbett is charting new territory in American, and Irish, literature. Their precision is striking throughout and demonstrates a remarkable ability to distil complex ideas into concise, impactful sentences – it has the markings of a work from a writer in a much later stage of their career. Having demonstrated such mastery from the outset, Hibbett is sure to leave an indelible mark on the world of literature and I look forward to seeing their success unfold.

Gustav Parker Hibbett will be speaking at the Cork International Poetry Festival on May 16th, at the International Literature Festival Dublin on May 19th, the Listowel Writers’ Week on May 30th and Books Upstairs on July 11th for the launch of the collection. High Jump as Icarus Story will be published by Banshee Press on July 4th, 2024.