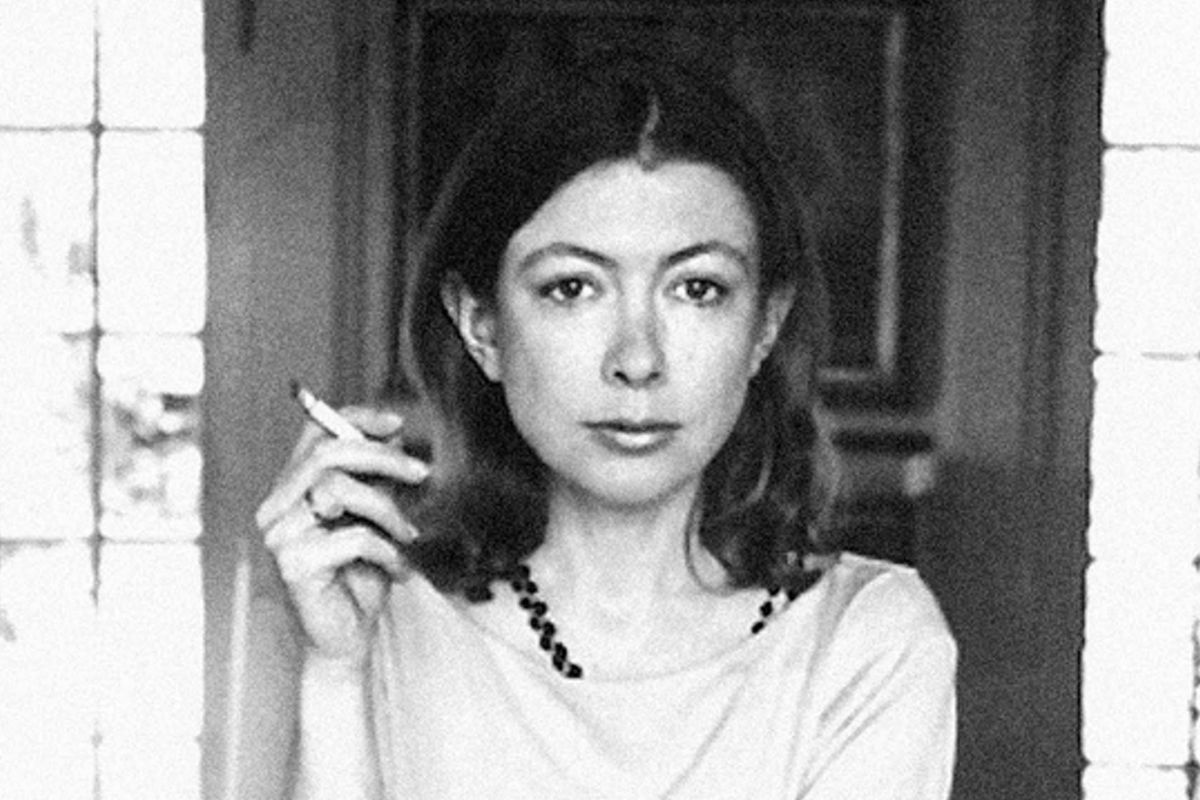

When asked about her style, Joan Didion claimed she learned it, in part, by retyping the stories of Ernest Hemingway. “He taught me how sentences worked”, she told an interviewer from The Paris Review. Through imitation, Didion began internalising his structures to begin expressing her own ideas. Despite his influence being tangible in Didion’s later writing, nobody doubts her own unique power, one entirely distinct from her predecessor. But why is this form of early imitation so important?

Each year, the summer period offers a selection of creative writing workshops to budding young authors. From The Stinging Fly to the Irish Writers Centre, artists are given a space to develop their writing practice by engaging with other determined participants. Often, they’re marketed as a way of helping writers “find their voice”. Implicit in this is the assumption that most inexperienced writers are burdened by the cacophony of other writers’ styles when they approach their own work. Read Woolf at the beginning of the week and you will be writing like her by the end of it. Such is the predicament of the imitator. Yet, despite the derogatory undertones of immaturity and insecurity inherent in labelling someone as “imitative”, most artists advocate for the imitative model in the early stages of a career. Picasso famously argued that “to copy others is necessary, but to copy oneself is pathetic”.

With its roots in the classical Greek tradition of mimesis, much of human history has found value in studying models and attempting to reproduce them. Work that proved noteworthy either because of content or form was copied in order to illuminate the intricacies of its form, content and style. Once the fundamentals were mastered, writers could move beyond replication to innovation within those learned structures. This two-thousand-year-old tradition still trickles down into the contemporary writer as an “enabling, heuristic function” (Gorrell). However, plagiarism is distinct from imitation. Rather than mindlessly copying work, imitation is a means of deconstructing and rebuilding a piece with the goal of understanding how meaning is formed through stylistic and syntactic features. For the unskilled writer, imitation offers a way of freeing creativity by providing a cemented path to aid one through uncertainty. Despite the popular belief, it doesn’t stifle creativity but rather instils specific practices of articulation.

So the question remains: Are creative writing workshops that claim to help the budding writer escape the restrictions of imitation necessary? The answer is yes. We often gravitate to certain writers because they articulate a certain part of humanity that we, individually, can relate to. Within their distinctness, we spot room for our own experience to be slotted in and begin manipulating and innovating from there. If we cling too earnestly to those initial influences, we run the risk of diluting our own experiences to fit within the bounds of our inherited form. Creative writing workshops therefore aid artists through collective critique to separate the authentic from the borrowed. In doing so, one may graduate from the classical roots and enter more concretely into the realm of the contemporary.

Hemingway himself was influenced by Gertrude Stein and Cézanne, the latter was in turn influenced by Pissarro, and so the list continues. Tracing back this lineage, it becomes clear that imitation encompasses interpretation, observation and expression – and is something to be embraced rather than shunned.

For online workshops, see www.chillsubs.com. Chill Subs is currently offering a free personal essay writing workshop and frequently updates its website with new offers.