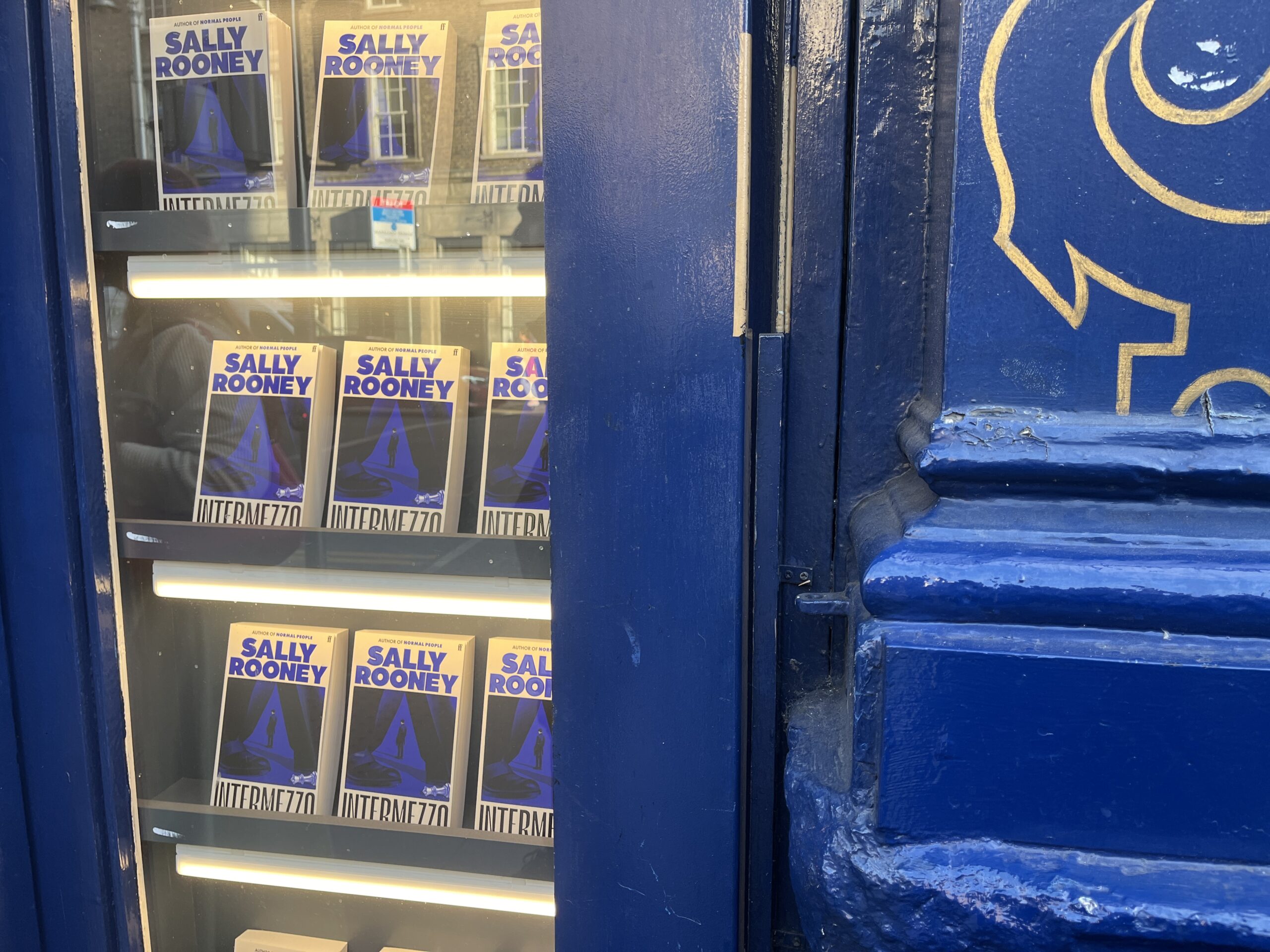

If ‘Normal People,’ ‘Conversations with Friends’ and ‘Beautiful World, Where Are You’ were the novels that made Sally Rooney a household name, then her fourth and latest novel, ‘Intermezzo,’ is her triumph.

One might be forgiven for drawing similarities between Rooney’s three previous works and subsequently expecting to open the pages of ‘Intermezzo’ to the relatively congruous themes readers have come to anticipate: relationships, sex and conversations. We expect to firmly plant ourselves in contemporary Dublin (and broadly, Ireland) and enter the lives of complex and often flawed characters. On first glance, those themes are as present in ‘Intermezzo’ as anything we’ve seen from Rooney in the past. The first pages of the novel detail an older man’s unquestionably complicated relationship with a woman more than ten years his junior– a familiar trope from Rooney. She’s no stranger to these uncomfortable conversations, and the first few pages of ‘Intermezzo’ lull the reader back into the familiar space they’ve come to anticipate in a Rooney novel.

What ‘Intermezzo’ carries, though, is something completely alien to the ‘Normal People’ of days past. The two central characters are both male, which is a new venture for Rooney. And as much as their romantic relationships carry weight, the most important one is that which they have with one another, strained and threadbare as it is. Ivan, a young, unassuming chess prodigy, and Peter, a successful thirty-something lawyer, are quasi-estranged brothers who are brought together by the death of their father. It is in the weeks following his death that we meet the two, each in the middle of their own chess game, balancing grief, love and family.

Rooney is having a lot more fun with perspective in ‘Intermezzo.’ And, like most of her prior works, the characters tend to jump off the page while the plot and its devices take a backseat.

Peter’s chapters are stilted and stream-of-consciousness. He speaks with no pronoun about himself, in short thoughts, in ‘shoulds’ and ‘should nots’. An iconic quirk of Rooney’s writing, her lack of quotation marks, becomes doubly more confusing when we enter Peter’s world – it’s an intentional choice that the reader can hardly tell what he says out loud and what stays as internal dialogue. It’s impossible not to make comparisons to James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’ and the closeness with which he holds characters like Leopold Bloom– Peter, like Bloom, is portrayed through a stream-of-consciousness standpoint, with haphazard trains of thought and runaway desires. At points, the perspective becomes nearly horror-esque, an unnerving funhouse of suicidal ideation and self-gloat. As he struggles between the young Naomi, with whom he has a blundering financial and sexual relationship, and his former lover Sylvia who suffers from chronic pain after an unexplained accident, Peter becomes more and more unspooled, abusing drugs and alcohol and tearing through Dublin in a very Bloom-esque manner.

Ivan cuts an awkwardly charming physique. Compared to his much-older brother, passages from his perspective are strategic and, in some ways, more distant: it’s a chess game of next steps and future consequences. If Peter holds the reader too close, too deep into his inner thoughts, Ivan is miles away in comparison. His fumbles into love with an older woman, Margaret, are more endearing than uncomfortable, though he’s certainly never graceful about it. Rooney seems to hold Ivan in a precious way: though he lacks Peter’s charisma, there’s a boyish and sincere appeal to how he sees the world. At many points, he presents as aeons wiser than the brother ten years his senior.

Although we’re covering new ground with familial relationships on a much more intimate level – all of Rooney’s past novels keep a considerable distance between the character and the family, compared to ‘Intermezzo’– Peter and Ivan’s relationship to the world around them unsurprisingly echoes that of other Rooney characters. They question their place in society, criticise capitalism (Ivan due to his unemployment status, Peter regarding his relationship with a sex worker), and toil with the difficulty that love presses onto their lives.

To call the conversations in ‘Intermezzo’ a ‘comfort zone’, though, is probably an underestimation. In fact, in ‘Intermezzo,’ through the exploration of Peter and Ivan’s respective internal struggles, Rooney seems to constantly be stretching, expanding her cultural lexicon onwards and outwards, touching grief and masculinity in ways she’s shied away from in novels past. Both Ivan and Peter’s respective inner turmoils about how they face the loss of a parent, about what is appropriate for a man to feel, are a new balancing act for Rooney, and one that she handles with grace.

Its plot may be different on its face than Rooney’s past toils with young love and relationships, but the bones remain the same. She still writes with a surgeon’s precision, her keen and focused understanding of interpersonal relationships nearly claustrophobic in how close it brings the reader to its characters. That is what will draw fans of her work back in: the comforting level of Rooneyism that ‘Intermezzo’ maintains. She’s growing, but in a way that’s entirely her own. After all, Rooney said herself in a recent interview with The New York Times that literary reinvention is a trite, unfair expectation to place on authors.

“I never think about [Intermezzo] in relation to my other work, and I never think about what people will say about how close or distant it is from my oeuvre,” she explained to the Times. “I don’t think of myself as even having an oeuvre...There is a huge cultural fixation with novelty and growth. Everything has to grow all the time. Get bigger, sell more and be different — novelty, reinvention. I don’t find that very interesting.”