Picture this: you are the son of Polish-Jewish revolutionaries who survived France’s Nazi occupation during WWII. You aim to be a good communist, but you have lived your whole life in the shadow of your parents’ brave nobility. You are a good man who has done bad things, but you refuse to compromise your values in order to prove it.

This is the argument Pierre Goldman makes to prove his innocence in The Goldman Case (Cédric Khan, 2024), a retelling of the relatively obscure true story of a Jewish communist in France who, accused of killing two women in a botched pharmacy stick-up in the ‘70s, published a tell-all book from prison and was granted a retrial in 1975.

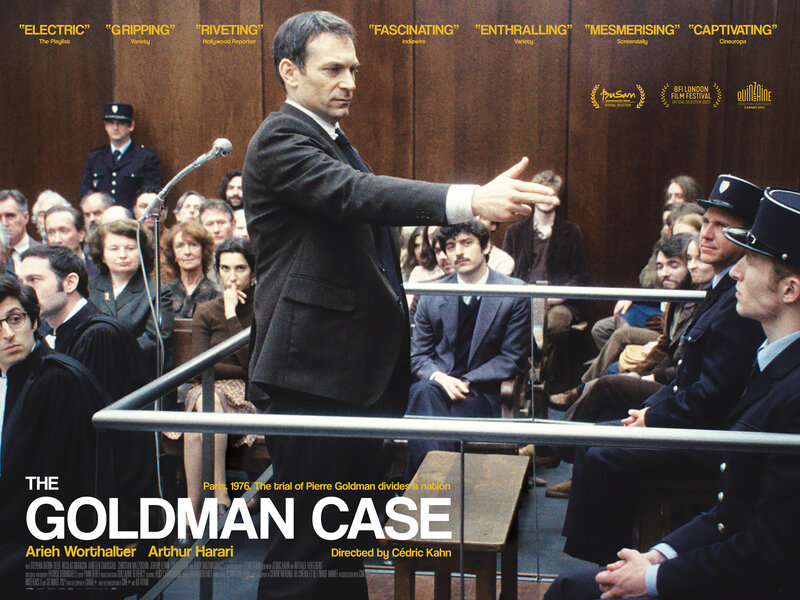

It is not a fast-moving film, unfolding instead like a beautifully rendered courtroom drawing, following in the footsteps of the recent uptick of nuanced and well-done courtroom dramas in France. But here, we are offered only a few sketched-out details of the case (Goldman had pleaded guilty to victimless robberies and had a history of violence) before the film launches us almost immediately into the claustrophobic world of the Parisian Palais de Justice courtroom, overturning our understanding of the nature of perception, identity and testimony as it goes. Levez-vous, because this is a bit of a sticky one.

Goldman insists to applause from his left-bank fans in the crowd, that just because he has done bad things, does not by default make him guilty of any similar crime without sufficient evidence, asserting that the police’s prejudicial laziness has simply made him an easy target. Goldman is undeniably identifiably Jewish, and relates much more to the otherness of the black Franco-Carribean experience than to the French white one. In standing up against police threats against black people and racial profiling (where witnesses initially testified that the gunman had a darker complexion) as a white man, he uses his relative privilege to raise awareness that while France may claim to be judicially race-blind in theory, in practice it is anything but.

But this is not Suits, and the film does not hold our hand through the moral maze of this complex case. While it is moving to hear the support for Goldman in the room, the camera’s unwavering gaze as eruptions of cheers drown out the ongoing trial, raises the question of whether Goldman is as much of a victim as he thinks he is. His claim that he was persecuted for being poor and Jewish, is the exact same reason his story gained such popular traction in the first place. “I don’t want anyone to say I acted like a Jew who implied a non-Jew has no right to think a Jew can kill, and those who do are antisemitic,” Goldman tells the court at the end. The camera is tight on the stripped-back room, and as we work our way through a faithful account of what actually happened (the script is compiled of direct quotes from his trials), we are rendered the ninth juror in the case, left in the dark about what we should think, buoyed only with our own preconceptions and prejudices, and those of other people, right through the trial’s closing arguments.

The Goldman Case is a quietly polished film, less concerned with any particular individual or their bon mot, than with how real justice can be carried out, and the danger that comes with viewing any one person or institution as inherently neutral. In the end, two women are dead, and it’s unclear who we should actually be cheering for. But the film makes a strong case that, like Goldman did, for justice to be fair, those in power must learn to become aware of their institutions’ own human shortcomings.