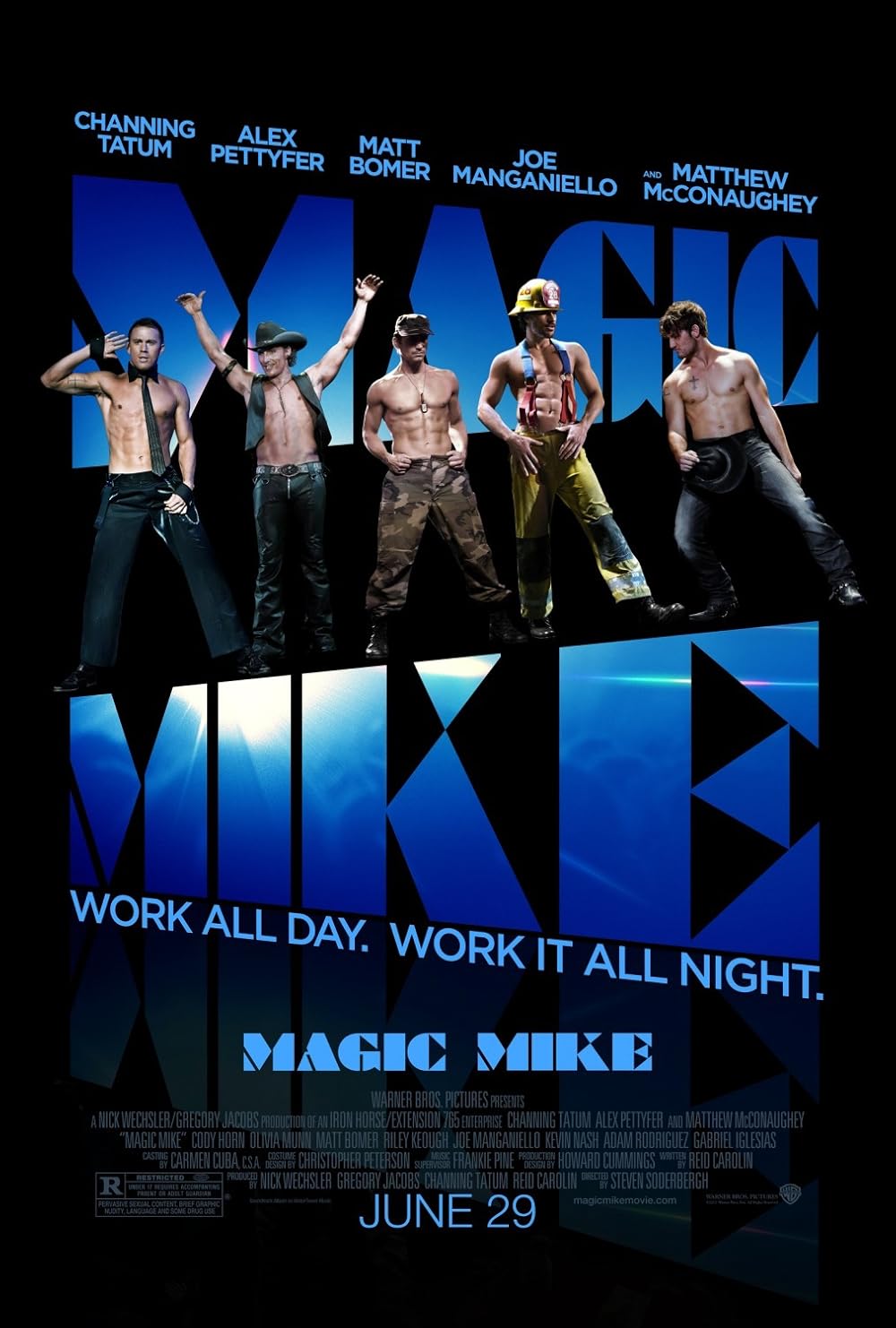

A crisis of masculinity is brewing, they say. But even though opportunists, like the candidate for United States vice president JD Vance, rag on cat ladies and call for men to go to war, what’s pegged as a masculinity problem is really the symptom of a society plagued by loneliness. Magic Mike (Steven Soderbergh, 2012), a sanitised-sex film supposedly made for women of a certain age to enjoy after a certain amount of margaritas, might not immediately come to mind as providing a solution. But twelve years later, it is clear that nestled within this sleazy classic of impossibly jacked men and the perils of quick money, is a story about what we gain when care is reciprocated.

Most of the film takes place at night, but nineteen-year-old Adam (Alex Pettyfer) drifts into Mike’s (Channing Tatum) life in the daylight. Having recently been kicked out of college and sofa-surfing at his sister Brooke’s (Cody Horn), he scores a job at a roofing company by lying on Craigslist. Powerless in Brooke’s domestic dynamic with her horrible boyfriend, Adam strikes out into the night. On the yellow-lit strip he stumbles across fellow roofer Mike, who gets him into the club, persuades him to peel his hoodie off on stage, and just like that, Adam has broken his dancing ‘virginity’.

Becoming part of this world offers the directionless and isolated Adam an enticing way out. His life explodes with new opportunities. He kisses a pretty girl, gets a flashy new car and believes the sleazy club owner’s promise that the dancers will be given equity in the new club in Miami. After staying up together until sunrise, Mike backflips off a bridge and Adam scrambles over the edge after him. Their heads pop out of the water. Adam says “You’re going to be my new best friend”. Money, girls and a good time, Mike tries to persuade Adam’s sister. What’s not to like?

But the film, cast in the exoticist yellow colour grading of Western films set in faraway countries, also hints at the imminent threat that the exciting world Mike inhabits must turn sour. Stripping for Mike is not where fulfilment lies. It was a means to save enough money to start his own furniture design business. So he squeezes into a tight suit, and applies for a loan. But even though his looks do fluster the bank teller, the cultural capital he trades in (sex appeal), is not strong enough outside his world to win her over. His life-long cash-in-hand job has tanked his credit rate, and the woman turns his application down. He is now at the back-end of his thirties realising his dancing years will soon be over, and he will have nothing to show for himself on the other side of it.

The slightly too-long dance cuts allow the viewer to feel the monotony and entrapment Mike feels kicking in. As he begins to doubt the likelihood that they will ever be given equity, Adam gets only further caught up in the illusion that this lifestyle will eventually pay off. After the club owner threatens to cut Mike loose, Mike makes his exit, and Adam takes Mike’s place on stage. Smiling under the lights, he is no longer the cowering virgin. He is confident, buoyed by the belief that he will be uniquely special enough to avoid Mike’s fate. But it is lonely under the spotlight, and as long as he is on stage he will only ever be performing connection, never truly feeling it. The cycle will continue and the dream of Miami, and the satisfaction it promises, will never come.

After leaving the club, Mike heads straight for Adam’s sister Brooke’s door, and it becomes clear that this is not a film about either of these men. It’s about care, and this becomes synonymous with her. For most of it, we watch her try in vain to appease her selfish boyfriend and veer through the morning streets to get her kid brother out of his drugged-up stupor. The film practically never lets her leave the home. But in her conversations with Mike, we see she is likeable and funny, and the chemistry between the two is undeniable. Towards the end of the film, she finds out Mike has put out yet another of Adam’s fires in a way that, let’s say, would put Mr. Darcy to shame. It’s obvious: Brooke’s no-nonsense big heart brings out the best in him.

In the end, Mike gets to trade performing a version of himself and being pawed at with damp one-dollar bills for mutual care and getting to be truly known. Brooke gets to be appreciated. And while it would be easy to dismiss this aspect of the film as relief porn for the women in the audience who can only imagine catching a break from the disproportionate burden of care that they bare, it’s also a powerful example that in societal structures that place such emphasis on individual economic growth, caring for each other is the only way out.

Adam, like many young men today, is looking for a guiding light, vulnerable to be exploited and sold a self-centred dream. But unlike Mike, he has to learn that life is where the people are. Magic Mike highlights that the magic of masculinity lies not in the traditional role of waiting for care to come to you, as cynical agitators would have you believe, but in choosing to actively show up with care for the people you love. And it concludes that maybe, with any luck, they might just do the same for you.