This review contains spoilers.

Watching the trailer for Sean Baker’s new film Anora (2024), you might think at first that it’s a film about sex work. Then it’s a whirlwind romance. Or a buddy-cop-comedy. But as the film closes out on Anora weeping into the arms of a bald Slavic man who she refuses to kiss and whose dick is still inside her, you might not know what to think.

Baker is an expert at making refreshingly colourful cuts into the underbelly of life for many North Americans. His films are driven by their people, often women, who have smart mouths, strong wills and whose lives could clearly have turned out very differently if they’d been handed a different card in life. From following two black trans women through the streets of Los Angeles as they investigate whether one of their boyfriends was unfaithful while she was in prison in Tangerine (2015), to the life of a single mother living in a motel near Disneyland struggling to make ends meet viewed through the eyes of her pre-teen daughter in Florida Project (2017), his films are social realism fed on neon drive-thru fries.

Anora is the confident product of all that Baker does best. The film opens with a long tracking shot that cuts into the line of private cubicles to show us half-naked women dancing on men. The scene establishes that this will be a film about the exchange of currency –of money, of sex, of youth – and sets the tone that Anora’s world at the start is one where intimacy is physically performed without ever being truly vulnerably felt.

We follow her (Mikey Madison) as she uses her good looks and charm to hustle in a New York strip club. The men we see her proposition are exactly who you would expect them to be — red-faced, old, and entirely forgettable compared to her. Forgettable, that is, until boyish Russian import Zakharov (Mark Eidelstein) arrives. He is pretty and rich, and so earnestly care-free that he can make her forget she is being bought. She starts escorting for him, coming out to his glass mansion in upstate New York. ‘You know you paid for a full hour’ she doe-eyed reminds him when he finishes early, and that’s when we realise what is happening. Our stone-cold protagonist has caught feelings.

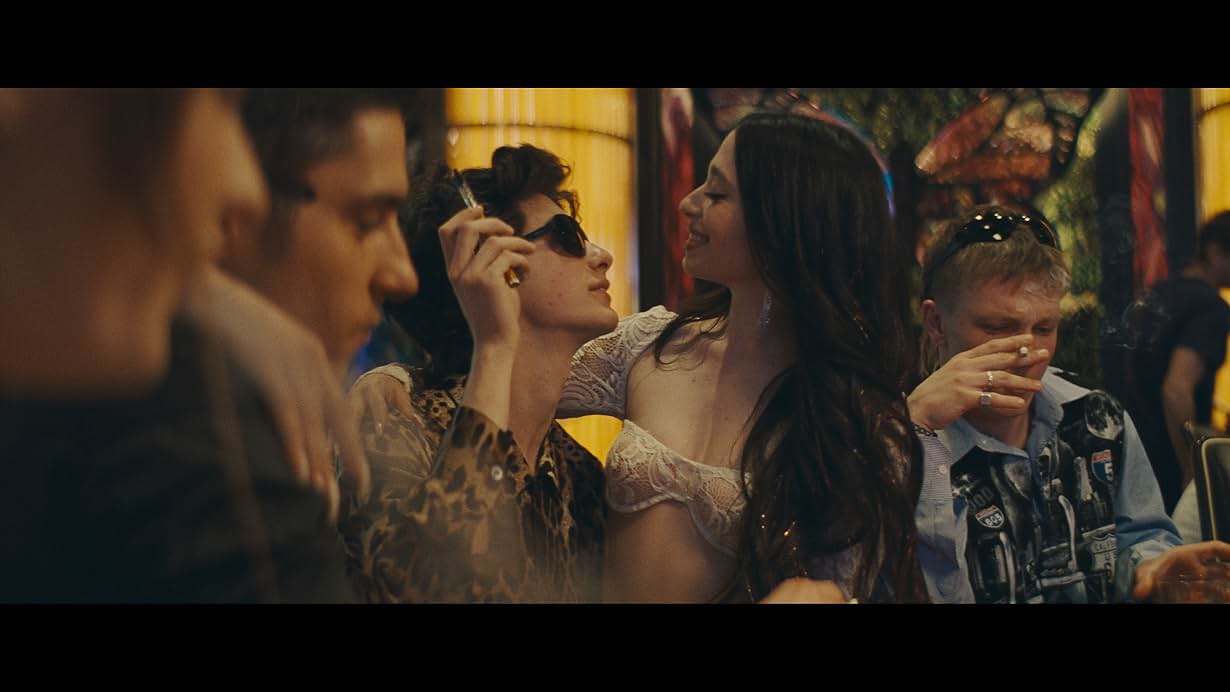

Within a few weeks, they are getting married in Las Vegas, and suddenly, what starts as Showgirls (1995) becomes Romeo and Juliet in alternate universe of Uncut Gems (2019). She quits her job and moves in with him, and they run giggling, hand in hand through the city. They go on shopping sprees in malls and throw parties in private hotel suites. He takes her to hang out with his friends who work at a sweet shop in Coney Island. Their manager is partially deaf and blind (‘he’s basically Helen Keller’), so they tell her she can take whatever she wants. Zakharov lives in a world of youth without restriction from authority, and through him Anora gets an electric taste of a world she would never otherwise have access to.

But Take That’s Greatest Day has played too soon, and soon the Molotov cocktail of their romance explodes in their faces when Anora realises Zakharov hasn’t told his parents about the marriage because he is ashamed of the fact she was a stripper. Where her confident sexuality was once a source of power and his carefree access to money was his power over her, both of their initial strength ultimately comes to be their downfall. Zakharov will never be free to make his own choices without his parents’ influence – because of the money they give him – and Anora will always be a citizen of the world where sex is for sale.

As a result, Zakharov’s parents send in three henchmen, Toros (Karren Karagulian), Garnick (Vache Yovmasyan) and Igor (Yuriy Borisov), to get them to annul the marriage. Zakharov makes a run for it, leaving Anora in their bungling hands. She kicks and screams until she comes to the realisation that the man she thought she was in love with is not coming back. The wide-eyed Igor holds her down and eventually Anora agrees to a divorce. The four of them get in Toros’ 4×4 truck and drive through the city trying to track Zakharov down on his drunken rampage, and the tension doesn’t let up.

It is funny and it is sad. Anora has been betrayed. As her greatest day becomes her worst nightmare and she realises she has been betrayed, what could be a heart-breaking story soon becomes something else, because Igor is quietly there to witness it all. He is there to hold her when Zakharov first leaves. To hand her a drink when she has to overhear what Zakharov’s nasty mother has to say about her. To be a shoulder to sleep on when she has to fly back to pack her stuff from Zakharov’s house. And although she says he has ‘rapey eyes’, it is obvious to us that this is finally someone who cares about her without expecting anything in return.

In the end, Igor represents filmmaking itself. When Anora first falls for Zakharov, she gets so wrapped up in his world that we almost forget she is the film’s titular character for a reason. Igor exists as a validating witness to the terrible way these people who have too much money for their own good treat Anora, and to be completely in awe of the strength of her spirit. We see all of her: her anger, her shame and her heart and it only makes us like her more. She might not like Igor back, but the film offers us the chance to see that when real love comes, it will be peaceful, and it will be safe to be wholly yourself.

Anora closes out on an unshaking close-up of Anora’s face as she cries in the hum of Igor’s car. We the audience hold her and her hurt, and what might seem depressing is a cathartic release for her to let down her walls. In the end, the film stresses that in love and in film, radical acts of trust pay off.