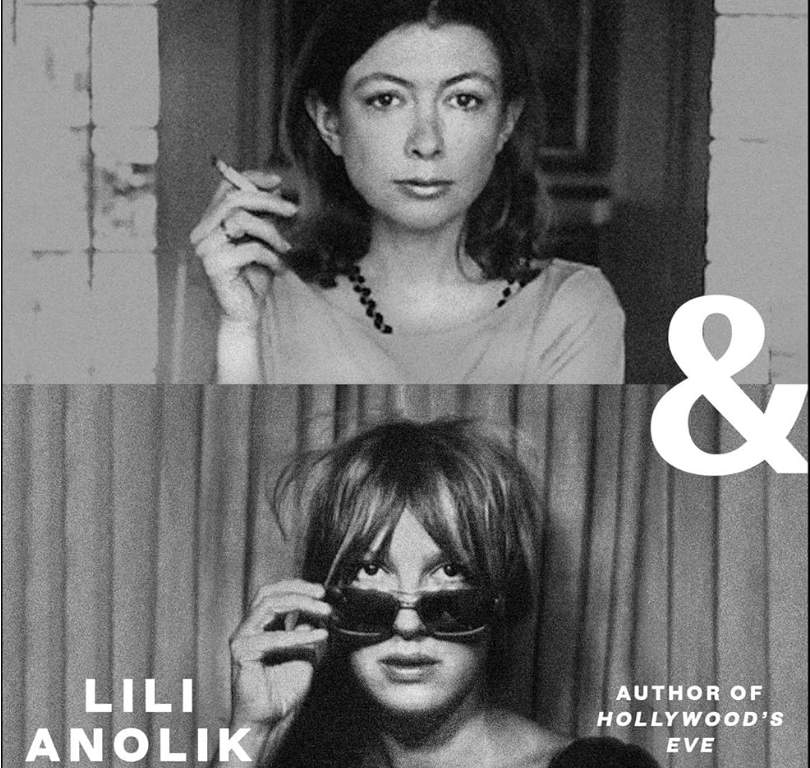

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik is 352 pages of photographs and prose relying on an imagined and quixotic relationship between authors Joan Didion and Eve Babitz exploited to denigrate the former and glorify the latter.

Joan Didion is best known for the novels Play It as It Lays and The Year of Magical Thinking, and is heralded as one of the greatest American writers of the 20th century. Eve Babitz was a visual artist and writer, best known for the novel Slow days, fast company, and her prominent place in the Los Angeles zeitgeist. “Children of L.A.,” Didion and Babitz both captured the ineffable and fraught milieu of California in the 1960s-80s. Anolik’s book is a dual biography, aiming to marry the two figures and argue that one cannot be understood without the other: at one point calling them “Soul mates.”

The book’s ostentatious and Instagrammable cover rivalling the Tom Ford coffee table book should tell a prospective reader all they need to know: aesthetics and frivolity are all Anolik will deliver on. Indeed, if one ever does actually crack it open, they ought to prepare for a long stretch of traffic on an L.A. highway. Sections about Babitz are tedious and plodding, with “a fan’s unreasoning abandon” (Anolik’s words) while Didion’s accelerate, relying on dubious anecdotes that prevaricate Didion as “part princess, part wet blanket”.

The book begins with an inflammatory (unsent) letter from Babitz to Didion reading “Could you write what you write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan?” inserted and analysed to enlist the reader into Anolik’s fantasy. She continues with Babitz’s characterisation of Didion as a “female male chauvinist pig” and a “double-crosser of women”. Anolik and Babitz express their fury with Didion’s unassuming and feminine nature, which she exploits for access and fame. However, Anolik has no problem detailing Babitz’s obsession with her own “Maralyn Monroe-like frame” that she believes her fellow women are jealous of. Even Babitz’s magnum opus Slow Days (which Anolik calls a “casual masterpiece”) details Babitz seducing her friends’ husbands, calling her female peers boring and unimaginative, and insisting she is only liked by men because women are so jealous of her.

Anolik’s writing is almost honest with itself twice. First, when she writes that she “naturally roots against Didion”. The comment is a throwaway but gets at the real reason she wrote the book. Anolik has a personal relationship with Babitz. Her previous book Hollywood’s Eve emerged from intimate interviews and eventual “friendship” with the author: she is “crazy for Eve”. Anolik truly writes about Babitz like a teenage superfan, preoccupied with defending her (though no one is attacking) and wasting pages insisting they are friends. The second almost honesty is when Anolik describes an anecdote about Didion from screenwriter Paul Schrader. Schrader had proposed an article about Didion, Susan Sontag, and Pauline Kael to capture the “West Coast female intellectual phenomenon”. He continued: “Each hated it more than the last”. It seems like a casual insert, but Anolik fails to get at why exactly she included it: Didion would’ve hated this book. I think Babitz would’ve too.

The truth is (which Anolik starts the book explicitly stating she intends to uncover) Didion and Babitz didn’t really know each other. The vignettes in the book of their interactions (which are few and far between) are disconnected, random, and in some cases accidental. They are two very different writers emerging around the same time both writing about L.A.. The accounts of Didion and Babitz taken without the gratuitous and obsequious pro-Babitz analysis from Anolik on balance paint a very bleak picture. Didion was a force of unrivalled genius with a complicated personal life, and Babitz was an it-girl and a good-but-not-great writer who was passively jealous of Didion’s success. As Marisa Metzler put it for the New York Times – “You end up wondering if Didion thought about Babitz much at all.”

Anolik goes mask-off by the end of the book. She calls The Year of Magical Thinking (a novel about Didion’s grief at the loss of her husband and daughter) fundamentally narcissistic, dishonest, and false. She calls Didion calculated, detached, exploitative, and ultimately unforgivable. But who is Anolik talking about? After wasting pages on random inserts like a picture of Babitz wearing Anolik’s sunglasses justified under the false premise of a “soul mate” relationship between the two authors, could it be said that Anolik is exploitative? Calculating? Detached? She was devastated by Babitz’s death in 2021, in this analysis is she calling herself unforgivable? Is Didion & Babitz unforgivable?

The experience of reading this book is a trafficky highway, and the reader’s destination is never found. Anolik leaves us with the desperate promise that “[Babitz] will become a totemic figure. Just you watch.” But the question has already been answered: It was always Joan Didion. It is impossible to overstate the importance of Didion. Her writing is the canon. Reading her for the first time is revelation– no one before her wrote like she did, and almost all writers try to write like her now – or try to write like someone writing like her. Didion is undeniable.

The book is deceitful. Not only because Didion and Babitz weren’t that close, not because the Babitz-mania severely undermines its analysis, and not because it slights Joan Didion. But because insisting Didion’s genius is not genius is gaslighting, and bringing one woman down to bolster another is futile and broken. We should not forgive it.