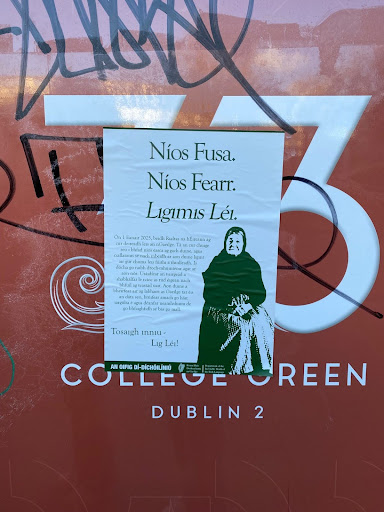

In the second century of independence, we as a country have a question to ask ourselves – does the Irish language have a place in our developing national identity?. If you took a walk around Dublin’s city centre in recent weeks, you probably saw posters bearing Peig Sayers face, and containing the phrase “Simpler. Better. Let’s Let it Go. From January 1st 2025, the Government of Ireland will be discontinuing the Irish language”. A closer inspection of the poster reveals that it was created and distributed by the ‘Office for De-De-Colonisation’, and supported by the ‘Department of the Inevitable Death of the Irish Language’. Fortunately, these posters are simply satire. However, what they highlight isn’t too far from the truth. It is no secret that for decades, government after government have failed to care or act appropriately for the Irish language, and this doesn’t seem to have changed with the latest general election.

Scouring through the party manifestos of the big three, it seems that few provide an ambitious plan to encourage the use of Irish in daily life. Fine Gael has pledged to “work towards” making all state websites and online portals available in both Irish and English, and will “explore” the possibility of further expanding the current requirement to print and publish 20% of advertisements in Irish. Fianna Fáil’s manifesto discusses the so called achievements that the party has reached during its term in the previous coalition government, such as the aforementioned 20% Irish advertising policy, and the commitment to ensuring 20% of new public service staff are proficient in Irish by 2030 (although they crucially failed to mention the level of proficiency that they would require).

Finally, looking through Sinn Féin’s manifesto, there seems to be a lot more enthusiasm for the promotion of Irish in daily life. Taking on Fianna Fáil’s failure to mention a mandated proficiency level, Sinn Féin’s manifesto states that a minimum B2 level (upper intermediate) would be required to fit the criteria of being proficient in Irish in order to fill Fianna Fáil’s mandate. Alongside this, the manifesto lays out ambitious plans to include Irish in daily life, by enacting ‘Ár Seacht nDícheall don Ghaeilge’, the party’s seven step plan to ‘normalise’ Irish in daily life. These plans cover a wide range of sectors, including the use of only the Irish version of place names in official documentation, bilingual food packaging, bilingual signage in stores, and more.

However, with the votes counted, it is almost certain that the coalition of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael will return to Dáil Éireann, with the help of another smaller party, or perhaps a handful of independent TDs. This leaves the Irish language in the same position it found itself in pre-election – which is absolutely not a good one.

But why should we even care?

It’s clear that despite the failure of successive governments to adequately act on the language, Irish has seen a major cultural renaissance in the last number of years. Whether you go to your local cinema, or even open spotify on your phone, Irish is slowly creeping into an English language dominated world. Recent successes in the film industry include ‘An Cailín Ciúin’, and ‘An Taibhse’ – the first ever Irish language horror film. You may also have heard of the film ‘Kneecap’, which follows the origin story of the band from Northern Ireland who switch between Irish and English throughout their rap songs. The band is known for their largely Republican views, and how they raise awareness for issues plaguing the North. Ironically enough however, despite the overwhelming Republican views of the group, this film was awarded with the title of ‘Best British Independent Film’ at the recent BIFAS.

On Spotify you will find the previously mentioned Kneecap, and you will find IMLÉ, a collective of Irish speaking musicians. Even Hozier included Irish in some of his more recent music. On a political level, Irish is rapidly gaining importance. In 2022, Irish became a full official language of the European Union, giving the language official status across the 27 country bloc. That same year, despite fierce opposition from some communities, Irish finally became an official language in Northern Ireland thanks to the Identity and Language Act (although there are still many ongoing issues with the act’s implementation in the region).

Looking at the census data for both the Republic and the North, the Irish language is spoken by around two million people across both jurisdictions on the island. Further filtering this, in the Republic alone, just under 200,000 people stated that they could speak Irish ‘very well’, while just under 600,000 stated that they could speak it ‘well’. That means that just under 800,000 people in the Republic believe that they can speak Irish to at least some degree of fluency. If we break this down again, around 72,000 stated that they spoke Irish daily in the Republic (outside of education). Adding in the further 44,000 that stated the same in Northern Ireland, we now have a figure of around 116,000 daily speakers of Irish on our island, and many hundreds of thousands more who speak the language somewhat well.

That’s still a small number…

In comparison to other languages (which have much greater promotion in daily life), Irish is a major language with a relatively large pool of speakers. Looking across the Irish Sea, for example, the Welsh language is much more present in daily life in Wales, and is much more visible than Irish is in Ireland. This is despite the language having an overall figure of 891,000 speakers, compared to the almost 2,000,000 Irish speakers on the island of Ireland. For example, road signs in Wales display both languages equally, making it possible to use either language when driving. Whereas in Ireland, the place names in Irish are smaller, and italicised compared to their English counterpart. Even on temporary signage, English gets the priority in Ireland (if the Irish translation is even included at all). There are several other examples of this type of comparison between Ireland and Wales, such as promotion of Welsh in supermarkets, sports and the availability of services through the Welsh language, amongst other sectors of daily life.

Regarding bilingualism elsewhere, there are numerous other countries in which two (or sometimes more) languages are promoted and protected in daily life. In Canada, for example, bilingual food packaging is mandated country-wide in English and French in order to be inclusive of the minority French speaking population. In Belgium, a similar system is in place to ensure that those who speak French or Flemish are not disadvantaged. Finland requires the same with bilingual Finnish and Swedish packaging in bilingual municipalities. In Malta, a discussion is ongoing as to whether or not the small island country should implement a similar policy, despite the fact that Maltese is spoken by around 400,000 people, and that almost all of them can speak English to a degree of fluency. In all of these countries, official languages are treated as equal, regardless of the number of speakers. If this policy can be mandated in other bilingual countries, there is no reason why it cannot be mandated here in Ireland, where both Irish and English are official languages, with the former being declared as our ‘national language’ in the constitution.

More importantly, regarding education, the vast majority of Irish students are educated through the medium of English. While education through the medium of Irish is on the increase, it is still far out of reach of the majority of people, with just eight percent of Irish primary school students being educated entirely through Irish, with this figure dropping to just below four percent at secondary level. This is not to mention the lack of courses available through Irish in higher education. It is also important to note that the lack of students being educated through Irish is not as a result of parents wishing for their children to be educated in English – it is as a result of the failure of successive governments to provide the assets necessary for expansion of this type of education, leading to a relatively small number of places available for students.

If you care so much, then why wasn’t this written in Irish?

Statistically speaking, the chances are that if this text was written in Irish, you wouldn’t understand it – and that is the problem. After over a decade of mandated learning in school, many students struggle to discuss even the most basic of concepts in the language. Most students appear more comfortable speaking a European language, such as French or Spanish, after a mere five or six years of studying, than they do speaking Irish after fourteen. This failure to adequately teach the language, alongside an unnecessarily stressful curriculum, leads to resentment amongst students towards the Irish language. Coupling this with the lingering sentiments from the British colonial period questioning the ‘usefulness’ of Irish, it becomes apparent as to why many Irish people today hold overwhelmingly negative attitudes towards the language.

Where does this leave us now?

It is clear that the political parties which have been in power since the creation of the state care very little towards our national language. Year after year, decade after decade they have failed to adequately address the problems surrounding the use of Irish, and instead have opted to continue the colonial-style anglicisation of Ireland by ensuring that students fail to grasp our national language in mandatory classes, and thus develop a resentment towards it. Instead, these parties favour the ‘token’ use of Irish in order to appear as being republican parties, who are in favour of the promotion of Irish. However, despite these factors, and with the odds stacked against it, Irish has most certainly made a comeback – especially within the younger generations. While it would most certainly be ‘simpler’ and ‘better’ for the government if as a society we ‘let it go’, any incoming government in Dáil Éireann faces an uphill battle if they truly believe that their English-centric policies will succeed in their longstanding quest to finally kill off the Irish language.