When Flow won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature Film, beating the likes of Inside Out 2 and The Wild Robot with its budget of three and a half million dollars, it was a win for independent film everywhere. Flow proved that Hollywood’s hegemony over animation is not unyielding and that it is possible to push creative boundaries with small-scale production, focusing on impression rather than detail to tell an impactful story.

The mastermind behind Flow is 30-year-old Latvian filmmaker Gints Zilbalodis, whose unconventional approach to filmmaking has finally paid off on the world stage. His first feature-length animation Away (2019) he wrote, animated, and produced himself, a feat rarely accomplished. To make Flow, he sought to expand his horizons and took on a small team of Latvian animators while remaining deeply involved in all aspects of the filmmaking process, from writing the script to composing the soundtrack.

Zilbalodis has recognised how the film reflects this experience: Flow is not only a physical journey through an unknown landscape but also a personal journey to self-discovery. It follows a cat as it traverses vast expanses of nature and is forced to band together with other outcasts to survive ever-rising water levels. Its cast of characters is composed entirely of animals and skillfully uses body language and behaviour to express ideas in lieu of dialogue. The lack of dialogue does not make the film silent. If anything, it makes every sound more audible and every movement more intentional.

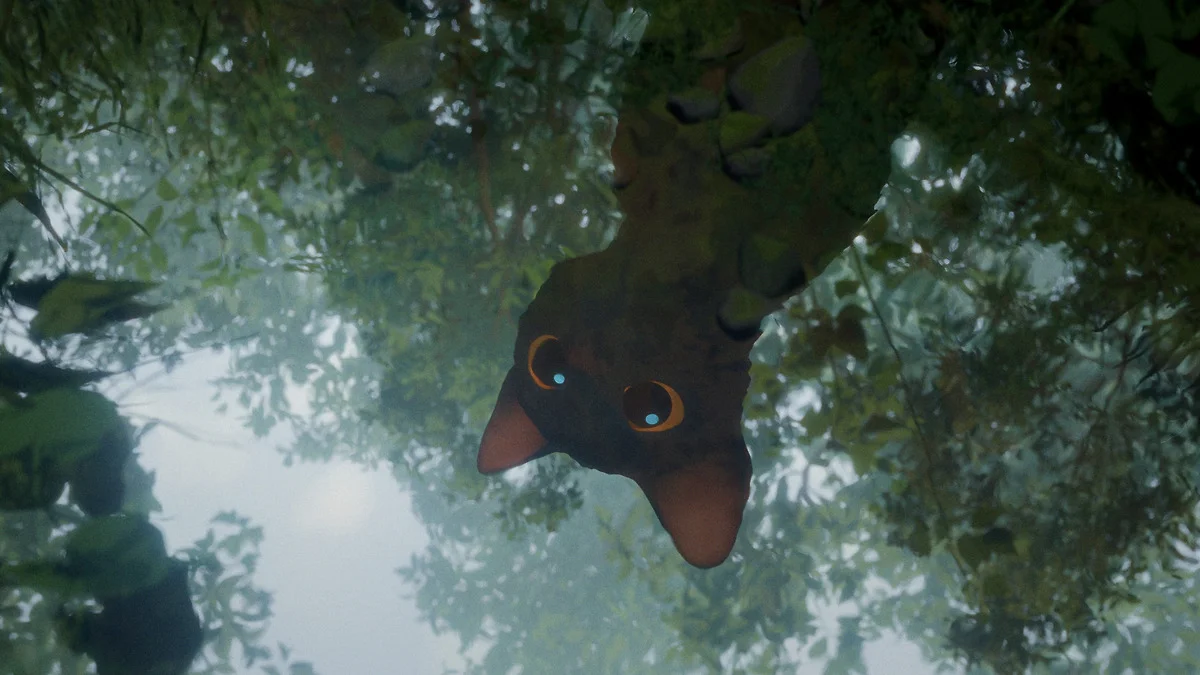

With Flow, Zilbalodis abandoned the industry-standard animation software used in Away and opted for Blender, which is both free and open-source, encouraging other animators to follow his lead. Flow does not aim for perfection and a polished look but leaves in those imperfections that betray the computer-generated imagery to reveal how it was crafted by human hands. It does not look unfinished, but it invites the viewer to participate in the creative process of animation as the scenes unfold. Remaining committed to a low budget and creative experimentation, the film used no storyboards. Normally, storyboards visualise the script and serve as a guide for the animators to make the scenes come to life. As he has explained in interviews, Zilbalodis would instead create rough models of the environment and explore them until he found the right camera angles, thus bypassing the step-by-step model of telling the story and, in a sense, letting everything happen all at once. The camera explores the environment alongside the cat, and Zilbalodis, leaving the viewer with the sense that they are uncovering the story in real time. The story unfurls intuitively – after all, this is the first time both you the viewer and the cat are experiencing it. The use of animal characters also allows the film more creative freedom to infuse the camera with a dynamism that would otherwise feel unnatural. This gives Flow an almost video-game-like quality, where the story pulls you in from the perspective of a playable character.

Connoisseurs of cat-related media will recall the 2022 video game Stray developed by BlueTwelve Studio and marketed as an adventure game set in a post-apocalyptic, cyberpunk-like world. Stray, like Flow, follows a cat that is forced to embark on a journey for its own survival, meeting characters and making friends along the way. Central to both is a journey, a path to self-discovery, and the adventurous qualities of Flow is what makes it feel like a video game. Stray has a clear end goal: to escape a walled-off city and return to the outside world. Flow is more open-ended, but it is still framed as an adventure with a set goal, even if that goal is not explicitly revealed to the viewer.

In Flow, mirror images follow the cat and serve as introspective breaks in the story, allowing time for self-reflection. Comparing the opening and closing scenes of the film where the cat sees itself (and its friends) staring back from a puddle of water reveals the growth we have all experienced watching the film. The recurring reflective surfaces make the film feel deeply personal but also invite us to collectively examine ourselves and our role on this planet. What stalks in the background of both Flow and Stray are memories of disaster and societal collapse. In Stray, the player seeks to piece together the city’s backstory to understand what happened before the game began. The only remnants of humans are the memories downloaded into a small robot called B-12 which helps the player in this task, but they are detached from their corporeal form and fragmented.

Flow takes a much more go-with-the-flow approach and chooses to leave the backstory and our role in it unexplained, but it is not difficult to draw conclusions from the combination of the lack of a human presence and the threat of natural disasters. In Stray, nature exists as something just out of reach but which occasionally intrudes on the built environment. In Flow, conversely, the built environment appears only sporadically and traces of human civilization are dotted across the landscape, but they do not fit together to form a coherent past. In the beginning, we see the cat enter the window of what appears to be a human cottage overgrown and abandoned. Later, a boat journey sees the group of animals pass by the magnificent remnants of an ancient empire. The imagined past of Flow lends it a mysterious and inexplicable element. In this way, Flow succeeds in breaking out of the constraints of its environment and transcending it, utilising only the most integral parts of it to move the story forward. Water is infused into every aspect of the story and gains a life of its own as it continually transforms itself to express various shades of beauty and terror. Flow is experimental, not in the sense of being difficult to follow, but in emphasising impression. Zilbalodis has claimed in interviews that the lack of detail in the world-building was intentional to shift the focus to the animals. The genius of Flow lies in using a non-human animal and a natural element to express universal ideas about both personal and collective fears and desires.

The animals are given human qualities but retain the quirks that make them endearing to us. They are sometimes vain, searching for instant gratification. At other times they express the pure kind of affection that only animals are capable of. In both Stray and Flow, the player/viewer is invited to feel a sense of responsibility for the cat and to protect it from the larger forces at play. The low vantage point of the small cat is juxtaposed with the immense natural world to reveal our insignificance. But the cat’s successful adaption to a situation that has spiralled beyond its own control also leaves viewers with a sense of hope, and what feels like dejection turns into acceptance in the end.