In 1988 one of the guests in Oprah Winfrey’s show was Donald Trump. There he outlined his discontent with US trade deficits and argued that America is being taken advantage of by its allies. “I’d make our allies pay their fair share” – he said, unbeknownst to all, revealing his plans for his second term as the US president. Funnily enough during the same interview he dismissed the possibility of running for office – “I probably wouldn’t do it Oprah, but I do get tired of what’s happening with this country.” Almost 40 years passed, and Donald Trump fulfilled his plan. But what do the liberation day revelation actually mean?

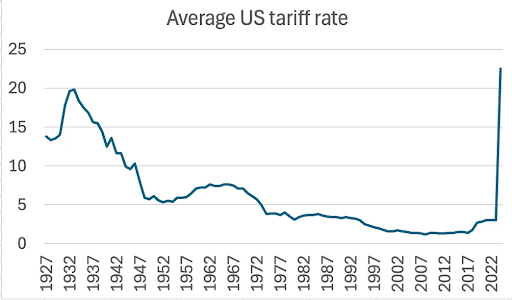

On Tuesday April 2nd, Trump unveiled his chart of reciprocal tariffs imposed on some of the US’s trading partners, on top of the 10% base tariff rate on everyone bar Russia and North Korea. This is Trump’s way to force the re-industrialisation of the US, a process which Trump hopes will bring about the golden era of the US, a boom of middle class manufacturing jobs, and lower the price of goods on the domestic market. All of this would come about from companies realising it was no longer profitable to manufacture goods overseas and import them to the US, instead they would reopen manufacturing sites in America. The second purpose for these tariffs is to balance out trade deficits between the US and its trading partners. A trade deficit between two countries describes a situation in which country A imports more from country B than it exports to country B. According to Donald Trump that’s how the US is being ripped off.

According to the formula published by the US Trade Representative, the level of reciprocal tariffs on any given country is equal to “its trade surplus with America divided by its exports to America”. A base rate of 10% was also set on all other US trade partners (that’s why Russia and North Korea are exempt from these tariffs, according to the Treasury Secretary Bessent, the US does not trade with these countries enough to warrant tariffs). There seem to be some issues with these calculations though. Some economists, like Noah Smith, suggest that the barrier levels are calculated based on a misunderstanding of the GDP equation, in which imports are subtracted by the end. Smith argues, however, that this is because they get added to consumption and investment so they need to be removed at the end to balance the equation. Another issue, raised by Nobel prize winner Paul Krugman, is that the trade deficit calculations seem to omit trade in services and only focus on trade in goods. If this is true, then the picture will not be true to reality and will be skewed against the US, in which services are responsible for over 75% of all employment. This category describes anything from financial institutions through health assistance to transportation. It has been understood that as economies develop, they shift away from manufacturing to a service focus. Not accounting for this massive sector will show exaggerated trade deficits, and not in favour of the US. Many economists also challenge the idea that trade deficits necessarily mean that a country is losing wealth, as Trump argues. Perhaps the most outlandish accusation towards the liberation day tariffs is that they were produced by AI models. Although, this claim will never be confirmed or denied so pundits should not cling to this idea.

But what exactly does Trump hope to achieve? There are three answers that most resemble a consensus. First – re-industrialisation, second – to lower the cost of US debt, and thirdly – it’s a negotiating tactic. There are also those who, like Jared Bernstein, say that all of this is Trump’s vanity play and has no deeper strategic justification. But even if Trump has a goal, all three possibilities aren’t without their issues.

First – re-industrialisation. Trump’s assessment of the US losing manufacturing jobs is correct and backed by studies. In the chase after maximising value by cutting costs, it was found that it’s cheaper to manufacture overseas, in developing economies, and import the products than it is to produce them domestically. This led to a constant increase in offshoring which changed the job prospects back in the US. Especially as service jobs were mostly focused around big cities, while factories were usually built out in the country. These people have also been some of the core republican voters. Trump hopes that by making it significantly more expensive to import than to produce locally, he will incentivise companies to manufacture domestically again. While sound in theory, there are issues here. Some of these problems can be located in how the White House went about imposing their tariffs.

Capital markets revolve around trying to invest in future profits. By having his tariff policy up in the air, Trump has greatly increased uncertainty about investing in the US. This uncertainty culminated in his Tuesday announcement which shocked many and severely harmed their trust in the stability of the US market and economy. This assessment is supported by over $5 trillion lost, wiped out from the US stock market just in the first four days of April, and by the slide of the USD exchange rate. According to economic theory, as the outflow of currency becomes limited, the supply shrinks. So if the demand stays the same, the price of that currency, in relation to other currencies, should increase. Yet the dollar fell. This suggests that the demand for the dollar fell too. Both of these factors entail that many investors would rather avoid the US market – and their capital would be, if not necessary, than very helpful in reestablishing manufacturing in the US. Aside from lack of investments there are other issues. The US has probably lost the know-how of running manufacturing operations. They lack supply chains necessary and many resources required. The US simply lacks enough qualified workers to sustain the highly technical manufacturing of our times.

If not to re-industrialise, then perhaps Trump is hoping to lower the cost of US debt – but how? The US government is over $30 trillion (sic!) in debt. And debt costs. The government has to pay interest fees to its lenders every year. Now, the cost of financing this debt is over $1 trillion a year.

One way to lower this cost, which now is the third biggest expense in the US budget, right behind social security and Medicare, is to lower interest rates. Jerome Powell, head of the Federal Reserve (Fed) said on Friday that he is not planning interest rate cuts. That is despite the president urging Powell to “cut interest rates […] and stop playing politics”. But the Fed could well be forced to cut interest rates, if they were faced with a crashing economy and a recession, a deep one. Recessions usually cause a spike in unemployment and a decrease in spending power, or inflation. One way of how recessions were dealt with historically, was lowering interest rates. In this scenario, Powell would be forced into rate cuts, which would lower the cost of financing US debt and allow Trump to claim victory over increasing government spending. The catch? If a recession big enough to force the Fed’s hand would occur, it would hurt all Americans, just like 2007 and 2020 did. Perhaps it’s a necessary sacrifice for the US to not default on their debt? Time will tell.

And lastly – tariffs being used as a negotiation tool. “Sit back, take a deep breath, and don’t immediately retaliate. Let’s see where this goes” – these are the words of Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent. “If you retaliate, that’s how we get escalation” – he added. This certainly is a bold negotiation tactic, one akin to slapping someone and inviting them to take a deep breath, think things over, while threatening a second, larger slap if they stand their ground. Some countries are yet to lay out their response, while others, like China, already imposed tariffs back on the US. And judging by president Trump’s affinity to having the last word, there will, indeed, be an escalation. But what choice do US trade partners have? First announced tariffs targeted Canada and Mexico. Trump agreed to postpone their implementation after getting satisfactory declarations from both countries. With liberation day tariffs some were hoping for the same. Israel removed all of its tariffs on US exports and still got hit with a 17% rate. Similarly the UK tried offering tax breaks for tech giants, which did nothing to remedy their 10% rate. This points to tariffs being inevitable. Why then should US trade partners accept them?

China was the first, rather than the only, country to respond. And if Bessent’s words and Trump’s disposition are anything to go by, escalation is imminent. This entails the US and its trading partners putting tariffs on each other’s exports back and forth, also known as a trade war. Trade wars, as you may assume, are the exact opposite of free trade – one of the core tenets of the last decades. All economies in the world started relying on imports. Supply chains and manufacturing chains became stretched and divided. A trade war means the end of free trade. Most countries won’t be able to be self-sufficient, but would rather not risk another trade war, which will probably lead to the formation of protectionist blocks on the global stage. From those blocks, the first ones to limit the flow of capital may actually benefit, so all players will race to limit trade flows and introduce capital controls, a race to the bottom. Economies have evolved to rely on free trade, they grew to be more specialised and fill out niches – something they could do because they relied on their trade partners to provide what they were missing. For many modern goods it is simply impossible to produce them domestically everywhere, because the necessary resources cannot be found everywhere. If these strategic resources will be tariffed, and as such an easy target they sure will be, this will either drastically increase price of goods or will even stop some countries from accessing them at all. There are no winners in a trade war, and the ordinary person can either lose a lot or lose it all.

The average joe is the fall guy: They either lose their retirement located in a pension fund invested into the US stock market, which was greatly pumped with foreign capital, which is now flowing out, or they lose by being faced with a deep recession, or they have to live through a trade war, which will probably bring about both other possibilities too. The full consequences of Trump’s liberation day speech will only be known decades from now, when all the processes set in motion last week have manifested themselves. But no matter how you view it, Trump has changed the face of the world. The iPhone era is coming to a close, and no one knows what will replace it.