The beginning of the print revolution can be traced to Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press around 1436, but it took centuries before a cultural shift emerged – a foundation of trust between the printed text and readers first needed to be built.

As ideas were exchanged through the medium of print, an industry developed to accommodate the rapid transmission of information. Although the way we engage with printed texts has evolved, the foundational authority ascribed to print persists. Whether students’ relations with academic texts today is undergirded by this same authoritative understanding of the printed text, however, is another matter.

Alan Galey, the director of book history and print culture at the University of Toronto, explains that “you can have a printed book in front of you, but in order to trust it, in order to have the relationship to it, that’s not just a matter of technology – it’s political economy, it’s the development of an industry”.

The question of whether students apply the same critical approach to printed texts as they are taught to approach digital sources with “goes right to the core question of trust, which is such an important theme in the study of print culture, and the study of digital media today”.

As learning-preference trends are incorporated in education, new demands for online access emerge. Technology has shaped the way we educate, research and learn. But to equip students – and teachers – with the skills to examine and operate within the digital structures of online research production requires digital literacy. Digital publication is not just a new approach to research, but is potentially transformative for access to digital learning platforms and academic discourse.

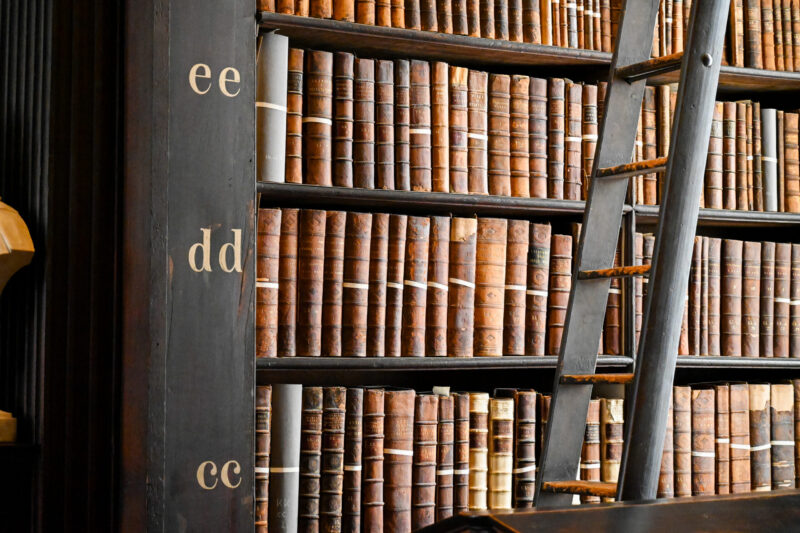

“Developments in technology have led to a deluge of information”, explains Siobhán Dunne, the head of teaching, research and user experience in Trinity’s libraries. Critical assessment of the authority and objectivity of sources, she says, is crucial. “The way information and data is sometimes presented – bite-sized chunks for easy consumption on mobile devices – makes deep-level learning challenging. I think the ability to cut out the noise and read a print book in a physical library can offer a refuge for students and importantly, set up a student for a deeper learning experience.”

The way information and data is sometimes presented – bite-sized chunks for easy consumption on mobile devices – makes deep-level learning challenging

Although the pandemic disrupted the ways that students and researchers engage with texts, it levelled the playing field in terms of access. Dunne explains: “We were very mindful of students who weren’t able to access online content during the pandemic and our postal and ‘scan-on-demand’ services went some way to acknowledge this. I believe one of the legacies of the pandemic will be a consideration by the university community of a broad diversity of learning approaches. One size does not fit all – and whilst some students prefer to learn with a print book, others are appreciating the value, not to mention the necessity, of the ebook.”

As the pandemic generated an unprecedented reliance on online sources, the possibilities and demands of new learning devices grew. However, Dr Christopher Anderson, a professor of media and communication at the University of Leeds, argues that this shift to exclusive online learning was underway before restrictions on library and bookshop access were implemented. Anderson says that “currently we’re in a situation where there’s almost no print material being used in classes at all.”

Although modes of learning and access to texts “changed dramatically” since before the pandemic, Anderson suggests that the lockdown period accelerated this change and “more or less turned the entire student experience and the entire educational experience into a digital phenomenon”.

Although physical access to books was inhibited during the lockdown period, the financial barrier existed beforehand. However, Anderson suggests that reducing the printed text to an exclusionary learning tool is incorrect. “We assign the value to a particular format of learning or education only in comparison with everything else … the object itself has not changed. In fact, some of these textbooks have been the same ones for 50 years, just with new additions. What’s changed is that the larger media ecosystem of which they’re a part has changed. And so students are now entering this media ecosystem with a radically different expectation of what else is out there and what else is available”.

Affiliation to totemic objects like books could be understood as a product of consumerism, but this understanding belies the sacred status they are afforded in the academic world. The constructive use of books, other than as objects of social posturing, as sources of community and objects of examination, are vital to literature in academia.

Dr Deidre Lynch, the Ernest Bernbaum professor of literature at Harvard, explains that in the 18th century, the development of literature intersected with a remapping of “the self” by which literature became “a site of our feelings of devotion and veneration”. Lynch says that “the danger of that is perhaps the assumption that to read critically is therefore sort of sacrilegious, as opposed to being more responsible to the text or more attentive to the text.”

Currently we’re in a situation where there’s almost no print material being used in classes at all

Lynch suggests that the digital sphere has eroded the notion of the author, or attention to the author as the central organising figure. She explains that “the digital erases the distinction between one author and another, because it’s so easy to click another link and go very far from where you started. Whereas one of the great impulses of the Canon formation period in the history of print was to gather up authors’ works and put them in uniform, bound editions, where there wasn’t the leakage that there seems to be in the digital universe, where you can very quickly start with with reading the work of one particular writer and then find yourself reading another and not even be very attentive to who’s writing it at all”. The potential implication of this development is that the authority, relevance or subjectivity of the author might not be subject to rigorous interrogation.

Although “the digital has changed the class dimensions of literacy and of the love of literature”, the potential for individual association has not been realised in the digital sphere, or at least digital resources have not been afforded an equivalent sacred status to the materiality of books. “That notion that the physical book can be a kind of mirror is, I think, really interesting, and I’m not sure that digital reading has found a way to mobilise the faculties of autobiographical memory in the way that the physical book does.”

The authoritative status of print, Galey suggests, is not just found in its physicality but also the barriers to publication, including costs, peer-review, editing, and maintenance of industry standards. He explains that this process “can be a barrier for unfair and unjust reasons, but it also can be a barrier in a good way too. An excess of information can be just as dangerous as a poverty of information.”

He concedes, however, that “there’s a fatigue that comes with the sense of information overload … fatigue can also come from a sense of helplessness if people don’t know how to interrogate something. And you see, it’s not as though we don’t have those skills, or it’s not as though those skills don’t exist and can’t be taught. It’s a matter, I think, of having faith that people, if you give them the equipment to be able to verify,” will ask the critical questions, which are “not unanswerable”.

Methods of research validation and the processes involved in traditional academic publishing may need to be reconsidered for the digital sphere. As the success markers for research are examined, the oblique algorithms structuring access to information and defining the relevance of online sources emerge as an issue of concern.

There is this idea that if it is in a printed book that you are reading for class, and that is a textbook, it is almost certainly the most authoritative thing you’re going to be encountering in your student journey

Galey stresses the importance of remembering that “when we’re talking about digital technology, or digital media is that we have a tendency to attribute to the medium or to the technology, things that are actually the results of human choices”. Defining the literacies at work and the inflection of human agency in information access – and gatekeeping – is crucial.

Dunne explains that “just because a journal paper has a high number of downloads, does not infer that that paper is an authoritative source. Likewise the ‘journal impact factor’ which measures the relative importance of a journal within its field (based on the number of citations its papers receive), is not a proxy for quality. The impact factor is built on a reputation economy where success is predicated on the ability to get published in a prestigious journal ahead of the ability to replicate the research or the ability to measure its impact on society”. Examination of citation, peer network discourse and the availability of data sets for further research or replication are necessary.

Dunne explains that “it’s important to divorce authority from format. Whilst it’s definitely easier, not to mention faster, to spread misinformation online, publishing content in a physical format be that a print book or newspaper, does not necessarily infer that the source is authoritative”.

Anderson suggests that “there is this idea that if it is in a printed book that you are reading for class, and that is a textbook, it is almost certainly the most authoritative thing you’re going to be encountering in your student journey”. In the online sphere, various genres of text are “all flattened to a degree wherein they all occupy the same territory. And you have to be educated and taught to absorb the fact that these things are all not produced in the same way and the people writing them don’t all have the same credentials and they’re not reviewed in the same way.”

As online self-learning and rhetoric in opposition to traditional higher education abound, this more equitable approach might be more consistent with university ideals. With dynamic interaction between the online and print mediums, these styles of learning are documented and restructure the ways that students and academics understand the sources by which education is constructed.

Galey explains that “reading has never just been one thing, it’s always been a moving target”, with intersecting textual boundaries. Although the death of the book has not arrived, it is possible that the commodified higher education system might become more conscious of the production, reception and democratisation of knowledge as our focus shifts to the digital sphere.