Stories are important. That might seem like an obvious thing to say, especially coming from someone who makes their living (literally) teaching the value of stories. But it’s true. As human beings, we’re wired to understand the world through stories. Everything, from science to history, advertising to finance, cooking to healthcare, just works better if we can recognise it as a story.

Think about it. Reading makes us more emphatic. Reading helps us realise that we’re not alone in the situations we’re attempting to survive, that we’re not the first person to think the way we think – and we won’t be the last. Stories, then, open up the world to us. And it’s our inherent duty as human beings to embrace that openness and to look. To look as far as we can into the world, and to stay looking, even when we want to turn away.

The job of students is to think. To find out new ways to see the world. The job of students is to look and keep looking – and to make sure what needs to be seen is seen. And in college, you learn on the job. Everything is new – and sometimes it feels overwhelming. You’re constantly challenged, inspired, devastated, transformed … and sometimes you just go to the Pav and wait for it to be the weekend. It’s all part of the job.

And I say that being a student is a job, not because it’s a chore (and certainly not because you get paid for it, because you don’t, not really) but because the work is worthwhile. Hard work usually results in change and change is usually needed. You’re learning how to be who you’re supposed to be, who you want to be, and that’s surely one of the most noble pursuits you can undertake?

But that noble pursuit comes with its own particular challenges, its own peculiar obstacles to overcome. The cost of living is simultaneously one of the most banal and existential phrases in the English language. How much does it cost to live? Well, a lot, as it happens. The daily, compounded stress of trying to figure out how much you have left to spend on food after you’ve paid your rent, the awful netherspace that marks the gap between the moment you run out of cash and the second your grant hits your account – and it’s always too late.

Sometimes you’re trying to study in a room that’s so cold and damp you feel like a Victorian orphan in a Charles Dickens novel. Sometimes, hours (and hours) of your day are lost on the commute, and you become so familiar with that particular stretch of motorway that it breaks your heart. You don’t get to go to that gig in town with your friends. You don’t get to go for pints after lectures. Everything just feels hard.

And yet, you still do the job. You do the thinking, you do the listening. You do the work.

I met my best friend in the queue for registration on my first day in Trinity. She was – and still is – from the United States, and she’s the reason I know it snowed in Wisconsin on Halloween. I think about that first moment of our friendship frequently, while also trying to gaslight myself into thinking it was only yesterday and not more years ago than I care to remember. I think about how fate can find you in a second, how other people can change your life just by existing. We became parts of each other’s stories that day in Front Square, and we’ve been writing fan fiction about each other ever since.

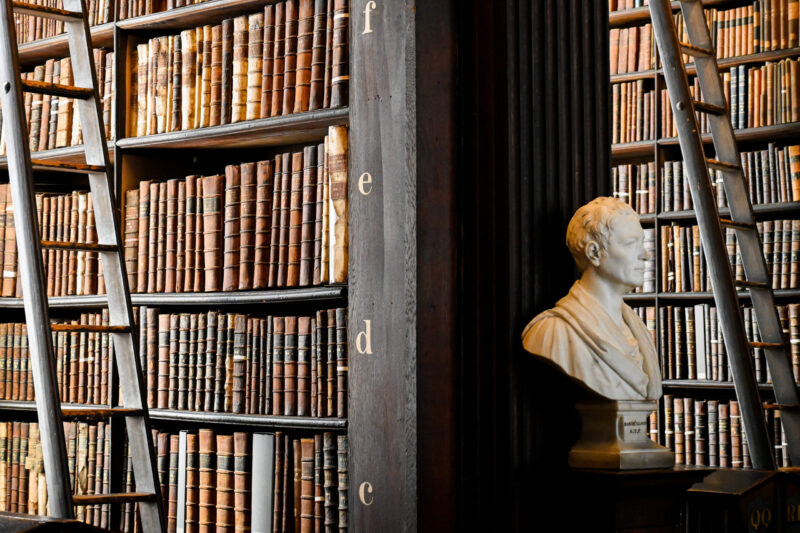

The books we studied during our degree still bind us together, in equal parts literary trauma and creative enlightenment. There are stories that are now embedded into my soul that I never would have found on my own, stories that now shape the way I see myself and my place in the world.

That’s the power of stories. With the concept of a connected beginning, middle, and end, we have the framework for an identity. Because what is selfhood except a sense of yourself in time? Who you were in the past, who you’re trying to be in the present, who you might somehow be in the future. That’s a story. And it’s your story.

I remember thinking, as most students do at some point in their degree, what was the point? Had I made the right decision? What other choice could I have made? (This may or may not have happened directly after a particularly challenging poetry tutorial where my brain ended up feeling emptier rather than fuller following some fairly unlively discussion). And the answer came surprisingly quickly. The learning was the point. The reading and the work and the writing was the point. That not one single second was wasted time. Because I was learning how to think for myself. By pulling apart some of the most famous and obscure stories ever written, I was figuring out what I wanted to think about the world. I was learning how to articulate myself. I was learning the value of my own thoughts. I was doing the hard work of building opinions. I was doing my job.

Because the job of a student is to create the world all over again. To embrace concepts as though you’re the first person to have ever heard them. To bring your consciousness, your particular context into communion with the wild expanse of knowledge that university offers you – and to make something new out of it. Because only you can do that. Because no one else is you.

When I think about it, I’ve had a lot of jobs in Trinity. I’ve been a student (many times). I’ve been a facilitator, I’ve been an outreach coordinator. I’ve been a lecturer. I’ve seen a lot of different sides to this old, old place, and I’ve seen it be remade by every person who walks in under Front Arch. If Trinity itself is a story, we’re all adding words and sentences as we go along – so not only are we part of the story, the story is part of us.

Trinity might seem like an intimidating place to be. Where you have to know the right people, and the right things to say. Where some people speak in a code that you can’t possibly understand, because you don’t even come from Dublin, never mind the leafy suburbs that seem to be the most common postcode in your year. But you belong here. You worked hard to get here – how hard, only you will ever really know – and you’ll work hard to stay here. You belong here. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.