Last February I moved to a new place. I had just begun my Erasmus and I was excited to get out of the city. See something new, meet some new people, hear about somewhere other than Dublin! These plans were somewhat quashed when I met my roommate: a Phibsborough native attending UCD. Within the first few weeks, he introduced me to one of his favourite podcasters, Blindboy Boatclub, by way of the Rubberbandits. I was hooked.

For those not familiar with Blindboy, this string of compound words must seem meaningless. Starting from the beginning, the Rubberbandits are an art/comedy/hip-hop group from Limerick – you may know them from their 2010 hit ‘Horse Outside’ or the more recent ‘Bertie Ahern’. The Rubberbandits have been known for covering a wide variety of subjects in their satirical, incisive voice; they are a duo, consisting of Mr Chrome and Blindboy Boatclub. Mr Chrome can now be found on YouTube under the name ‘Bobby Fingers’, where he creates fantastically innovative dioramas. Blindboy still goes by Blindboy Boatclub, and his primary focus has slightly shifted as well. Since 2017 he has published three books, all collections of short stories, with his most recent Topographia Hibernica published only a couple of weeks ago. He has also starred in a BBC documentary series, revealing the truth of societal issues through satire and on-the-ground investigation. If this wasn’t enough, the Limerick native is also the host of The Blindboy Podcast, an extremely popular show with over one million monthly listeners which Wikipedia describes as featuring “interviews and coverage of social issues”. This description is woefully inadequate. The podcast was started to promote his first short story collection, 2017’s The Gospel According to Blindboy, but it quickly outgrew this initial aim. Blindboy began performing long-form, scripted monologues about issues that he found relevant and relatable. This week, in the wake of the release of Topographia Hibernica, I was lucky enough to speak with Blindboy about his new book, his podcast and his process.

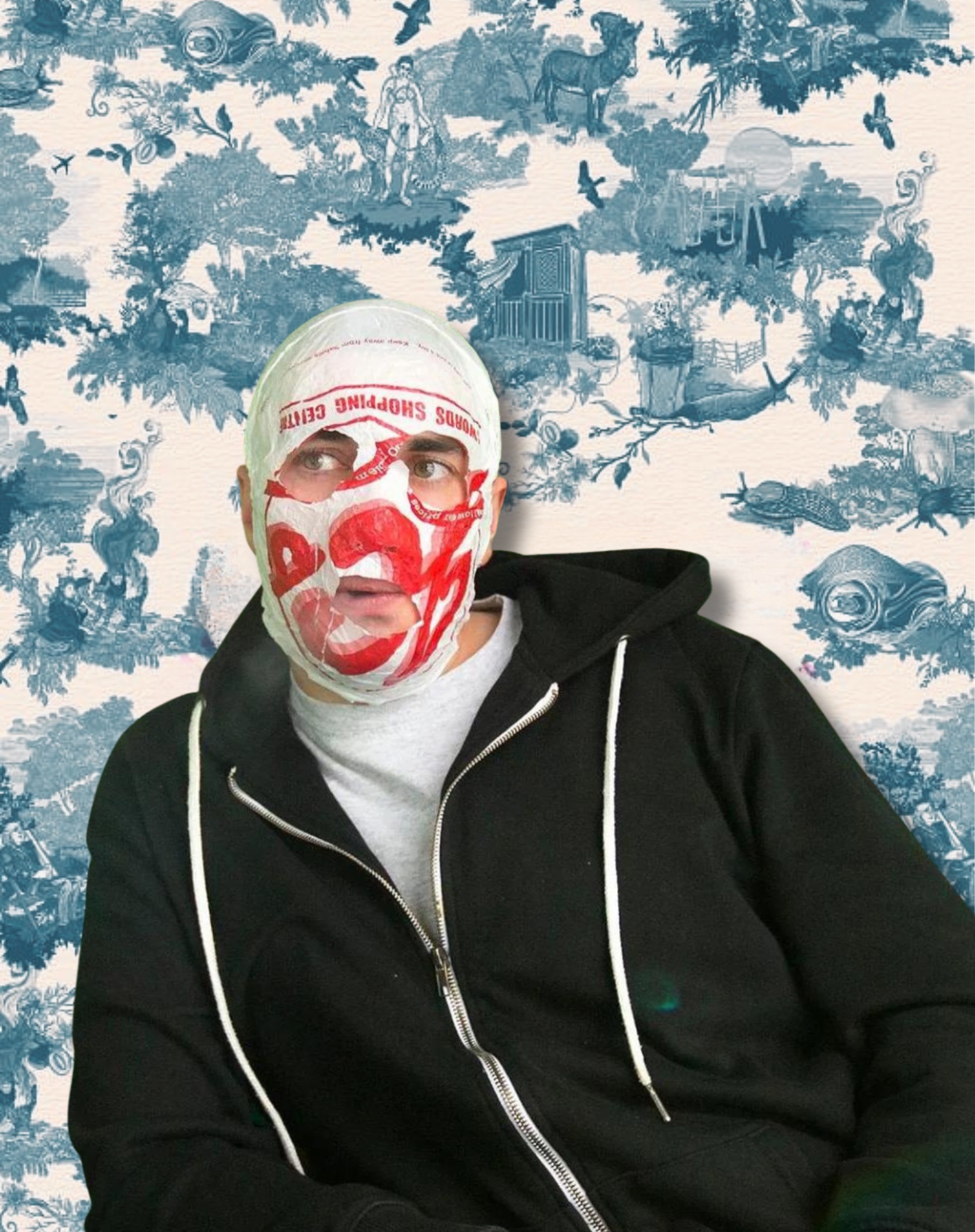

It is worth noting that if Blindboy is best known for one thing, it is his appearance. Blindboy only appears in public while wearing a bag on his head. It appears to be plastic, with two eye holes and a mouth hole. These holes have slightly widened over the years to show a bit more emotion. My interview with him was conducted as audio-only on his side. After weeks of putting on shows while touring and interviewing in his free time, all with bag-on-head, his reasoning was obvious. Blindboy’s bag-wearing has decreased since his Rubberbandits days; now primarily a podcaster and writer, there is less need for him to make visual public appearances. After he admits to me, “Blindboy’s a little cringy. I’m a full-grown man with a bag on my head, it’s like ‘grow up’ you know?” I pose the question: why wear a bag at all anymore? “Exactly, that’s what feckin’ pisses me off! At this point, I don’t even need the fuckin’ bag! Jesus Christ! I don’t even… It’s frustrating, that. But I have to go on fecking television to promote the book and I’m asking people ‘can you read my serious literature please? I’ve got a bag on my head, can you deal with that also?’”. Blindboy’s answer, self-effacing as it was, was buttressed with another explanation: “This is just so I can have a quiet life. […] It’s about saying ‘can I have some space here.’ I don’t want to engage with the fame hierarchy. I literally don’t care about fame”.

The bag certainly provides Blindboy with anonymity, and his interaction with fame itself is negligible. It is hard to name another celebrity whose public persona is so disconnected from their private life. “It’s not like the feckin’ Kardashians where you get to have bodyguards, I have to go to Aldi!” Blindboy provides one last, and extremely relevant, reason for his bagged head, “I’ve started to view the bag […] as an autistic protest”. Blindboy, who is in his late thirties, was diagnosed with autism only last year, and this diagnosis has profoundly influenced his art and his outlook on life. This is perhaps best evidenced in Topographia Hibernica’s ‘The Cat Piss Astronaut’, which follows a child who is extremely fixated on the planet Jupiter. His interest is repeatedly – though not always – made a mockery of, be it by his teachers, other parents, or peers. Blindboy says he wouldn’t have been considered autistic in his schooldays, “I would’ve been seen as just a misbehaving little prick, you know”. Being seen as a misbehaving little prick, the character is subject to scorn and vitriol, as Blindboy was himself. He mentions that he only wished that he could’ve had a note to show the teachers, one saying “could you stop being mean to this kid, please”. Admitting that he announced his diagnosis for similar reasons, he explains, “One of the main reasons I came out and said I was autistic is just for some people to stop being mean to me online”, an extremely understandable rationale considering the amount of hate Blindboy receives.

Blindboy describes his podcast as “an encyclopaedic novel about a lad called Blindboy and his curiosity about the world. […] It’s never-ending and it’s process-based”. Perhaps this is why Blindboy grates on some people – he is unabashedly different, and he is unashamed to show genuine passion and interest in the things he talks about. It is irrefutably encyclopaedic. In conversation with Blindboy, there is no social posturing, no false kindness, just passion. This passion extends everywhere, to the housing crisis, mental health and neurodivergence awareness. He explains, “You can’t remove the housing crisis from the mental health situation. You cannot. If someone can’t pay their fuckin’ rent or doesn’t know where it’s gonna come from, how can that person be mentally healthy?”. He is as passionate in his dislike for the Dublin Spire: “No… I don’t like the spire”. This was said emphatically, if the quotation doesn’t communicate this. This intent focus also extends to the home of the original KFC recipe, a place called the ‘Chicken Hut’ in Limerick. He’s interested in the giant lobsters that once roamed the shores of New England, the ones that indentured Irish servants were made to eat, whose overabundance resulted in the creation of surf and turf as a menu staple.

He’s a big fan of location-based Wikipedia viewing, going down rabbit holes of information, finding connections and making meaning. These rabbit hole explorations are apparent in his podcasting, as are they in his book, and they are extremely enjoyable to go down with Blindboy serving as guide and interpreter. For example, he only briefly mentioned monarchy: “If I’m bored, I pick a member of the English royal family, and just keep clicking on the blue tick of their parents […] until I eventually arrive at some Viking called Olaf the Brain-Eater. […] That’s what pisses me off about monarchy [..] I had a great-great-great-great-great-great grandfather who was profoundly violent, profoundly violent, and then he murdered everyone he saw, and then everyone put silly hats on and did a dance”.

Blindboy’s comments are at once hilarious and true – unless you’re a monarchist. Sorry. Our conversation covered extensive ground for having only been an hour long, throughout which Blindboy mentions Hemingway, folklore, sustainability, Liam O’Flaherty, Jungian Mythology, The Life and Times of Tristram Shandy, and why radio hosts tend to have an awkward flow when asking questions. Alongside Blindboy’s claim that his podcast is ‘encyclopaedic’, it must be said that he is encyclopaedic himself. Our conversation was dynamic and tangential, but there was never a non sequitur, and everything was somehow, amazingly, relevant. This is one of the greatest strengths of Blindboy’s work: he asserts that the mundane is meaningful, and he proves it. It makes his claim that his podcast is a novel seem less far-fetched, especially after reading Topographia Hibernica and realising just how intentional all of his writing is. This includes his podcast, which is meticulously scripted. His writing may at times be far-reaching and overflowing with information, but it is never careless.

The glummest refrain was our brief conversation about Dublin. When asked about the city, Blindboy states, “Dublin’s a strange, strange place because the thing is […] it’s a city that’s very much being designed towards tourism over and over again. […] It doesn’t feel like home. You go down to Cork it’s different”. But there must be something good about this city, right? “To be honest I know that this is the Dublin focus; it is difficult to say good things about Dublin, I’ll be honest”. While this opinion is not uncommon, some light did nevertheless emerge, as he reveals, “The best thing about Dublin is the history […] I can go down to St. Michan’s church and see a Templar […] go to Wood Quay and see a Viking museum”. This brought us to talking about an important point about Dublin, a question that the city asks itself over and over: “Why am I?”. Dublin says something like that. Its history may be fascinating – it is – but something is strange indeed. This conversation was had only a few hours before the anti-immigrant riots started in response to the stabbings on Thursday, and his comments regarding Dublin couldn’t seem more relevant in this light.

Last year Blindboy was the subject of a Trinity master’s thesis in literary studies. Ola Al-Hajhasan’s thesis, ‘The Voice in Authorship: Speech and Writing in the Blindboy Podcast’, contends that his podcast is not simply a podcast, but a work of autofiction, of meticulously constructed “literary monologues”, all of which are researched, written, and performed by Blindboy. Blindboy commented on this, “She did her whole master’s on why my podcast is Irish literature […]. To have someone dedicate a master’s thesis to back up that, it gives me great confidence”. Though he has courted controversy and criticism, Blindboy has unmistakably made a mark on the literary world. This is shown through Al-Hajhasan’s thesis of course, but it is most easily seen in Topographia Hibernica. The book is very much a personal project, but it also deals with larger themes: biodiversity collapse, the past and mental health are extremely prominent, to mention a few.

Speaking on these themes, Blindboy mentions a story by Liam O’Flaherty, set in the west of Ireland in 1920, featuring a river which appears silver as it is filled with fish. “Isn’t it so sad that I’m reading a story from 100 years ago, and I think the writer is lying because I’ve never seen a river that’s so full of fish that it’s silver”. Blindboy’s book grapples with this contention of collapse, of a lost past that seems unbelievable. This is especially apparent in ‘The Poitín Maker’, ‘Pistils of the Dandelion’ and ‘The Donkey’. The book is technically and formally beautiful, and every word seems to have been placed after deep thought and with great intention. It speaks to a world that once existed, as well as the world we live in now. The scars that colonisation and occupation have left on Ireland are evident, and the suffering of the land is articulated in a way which rings profoundly true: look outside, see Lough Neagh and its impending death, see the majority of native species that have declined in the past hundred years.

The book also calls for empathy, as does Blindboy himself, a “radical empathy” that can only be realised by attempting to truly understand someone else’s experience. This is perhaps the most essential, important theme of the book and of Blindboy’s other works too. The book and the podcast evoke the feeling of being in someone else’s shoes, this sense of occasional unfamiliarity. The stories can occasionally be uncomfortable and hard to read, but only for their intensity and emotive quality. Topographia Hibernica succeeds in advancing Blindboy’s unique style of empathy, his passion for life, and his curiosity about the world. Anyone with the slightest interest in literature, nature or interpersonal relationships, should pick this book up – it is a shorter read, at times mystifying and horrifying, joyful and mournful. Blindboy has put his experience of the world to the page, and he has done a spectacular job. He left me with a farewell which I will include here, in the spirit of his work and as an affirmation of its understated hilarity: “Dog Bless”.