In the midst of the pandemic, TikTok grew to be a phenomenon in an online field populated with various other social media platforms. Amongst its many subcultures, comedic skits and dancing videos to name a few, ‘BookTok’ emerged as one of TikTok’s most curious forms of content. ‘BookTok’, to those unfamiliar with the term, refers to a subsection of the platform in which users discuss and recommend books to audiences watching their videos. With 1.1 billion monthly active users globally, TikTok provides a unique opportunity for writers and publishing companies to access an enormous pool of potential readers who might otherwise be unreachable using traditional marketing techniques. Recent statistics illustrate this extensive reach with 240 billion views being recorded on ‘BookTok’ related videos, and individual videos attaining up to ten million views.

Despite many of the statistical findings being skewed towards studies in the United States, the influence BookTok has on reading activity in a larger global context is still staggering. Studies have shown that almost 50% of TikTok users have claimed to read more books than before their interactions with BookTok. BookTok has also led to tangible sales increases across many Western literary markets. However, is the natural conclusion from this that these changes are positive? The answer falls into a grey area between ‘yes’ and ‘no’.

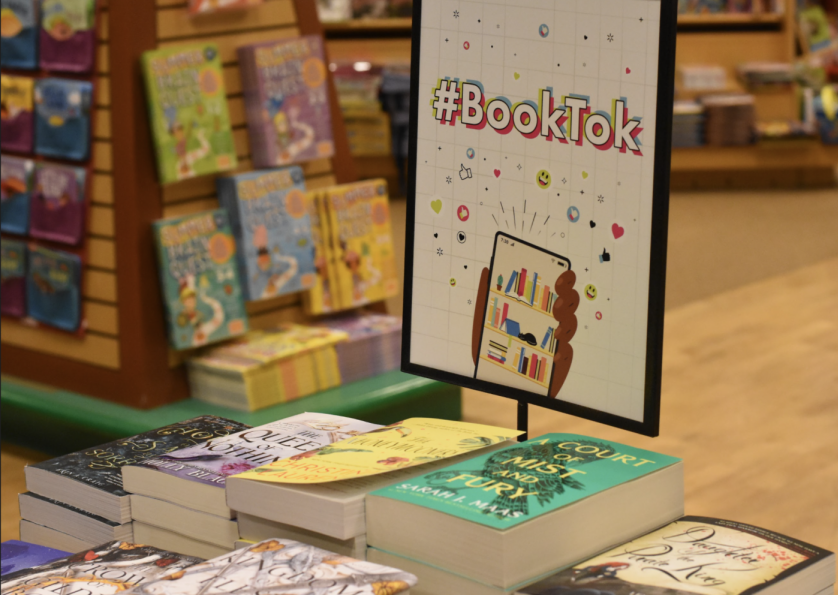

In the wake of the explosion of e-books following the release of the Kindle in the late noughties, combined with the lingering economic effects of the pandemic, an increase in sales to keep the printed book industry afloat is a promising sign. However, this increase has been shown to disproportionately favour chain bookshops owned by large corporations as opposed to their independent counterparts. The stock of many independent booksellers is secondhand and therefore large quantities of single titles are, in most cases, not available unlike chains that accommodate quantities in bulk. Beyond this, independent bookshops tend to have eclectic collections, whether secondhand or not, that are largely composed of works which may be considered more ‘literary’ than the popular literature of chains. Finally, chain bookshops such as Waterstones, who own the Hodges Figgis branch on Dawson Street, tend to tailor their merchandising precisely towards this emerging market with recommendation tables displaying the trending works of BookTok. Combined, these differences within the market extend the divide between independent bookshops and those owned by large corporations into a much larger gulf.

These changes do not begin and end with the market. They also affect which writers and genres we read. With BookTok and the larger corporate publishing industry being heavily skewed towards works of popular literature, titles that fit more neatly into binary generic categories and demonstrate the potential to be consumed by the widest possible mass audience are being prioritised. For works that bend the rules of genre and defy popular conceptions of narratives, their chance of finding a place within this online community is considerably reduced. The studies conducted have also pointed to the prioritising of certain demographics that most frequently engage with this subculture of TikTok — that of young women and girls interested primarily in romance novels. Writers such as Colleen Hoover, Taylor Jenkins Reid and Madeline Miller have witnessed this burgeoning firsthand. However, tailoring campaigns towards this demographic and driving sales based upon a narrow genre of recycled plotlines runs the risk of both excluding those writers and readers who do not fall within this category and cementing readers within the firmly familiar. Literary agents and publishers alike have admitted that this drive for romance has a strong effect on the writers they choose to represent and put into print.

In a world dominated by the screen, BookTok has emerged as a positive sign of a young generation’s interest in literature. Yet with this growing influence, it’s important that we continue to interrogate what is being featured, and more importantly, what is not. Moreover, there is a world of readers who do not engage with TikTok, or any social media platform. It is vital that new releases and back titles which remain in print also reflect the widest literary community possible, not one measurable solely through views.