The Irish border is at the forefront of the Irish collective, particularly for those closest to it. While the border is undeniably a setting for intense trauma, grief, and violence, it is also a place of immense creativity, particularly relating to the arts. This stimulation of creativity at a point of division was the central focus of Ireland’s Border Culture project, a collaboration between the Trinity Long Room Hub Arts and Humanities Research Centre of Trinity College Dublin and the Seamus Heaney Centre at Queen’s University Belfast. Their digital archive, accessible as an interactive map, was made through the curation of art that “show how cultural production, across all genres, is stimulated and provoked, often in unpredictable ways, by the difficult narratives of partition”, as stated in a press release for the project.

I sat down with the Trinity lead for the project Professor Eve Patten to understand more about the project and the idea of creativity in areas of partition. A professor of English and the current director of Trinity’s Long Room Hub, Prof Patten was deeply aware of “the gap between fossilized, top-down perceptions of a fatally divided society, and the grass-roots activities that characterized the vibrant communities of the area”.

The archival project received funding from the Shared Island Initiative, a government project aiming to increase cultural knowledge about Ireland. A team was built with vast knowledge on a variety of art forms, including photography, music, and visual arts. This team includes Prof Patten and Dr Orla Fitzpatrick of Trinity College Dublin as well as Dr Garrett Carr and Dr Aisling Reid of Queen’s University Belfast.

Having spent much of her life on the Fermanagh-Donegal border, Prof Patten has a specific interest in Ireland’s border as a setting for confused identities and the way that the past impacts the present. Prof Patten began the project by thinking primarily of the literature that referenced and captured border life in an everyday manner. The project, which exists on a website created with Dublin graphic design team NoHo, is divided into genres, decades, and connection. She explained to me that “one of the things I was really keen to understand was how unsettlement or disorientation or confusion of identity that you get when you have a partition actually stimulates creativity. People want to respond to it or refer to it.”

Prof Patten expressed to me that the team was particularly careful when thinking about representation.

“What I wouldn’t want ever to do is to fail to acknowledge that trauma and the grief and the violence and the suffering which has been caused around the border area,” she stated. Further, in reference to the fact that the border is marked by sites of memorials for people who have been killed, she said “we didn’t want to not acknowledge that. But this was a different way to think about the creativity that had been prompted by the existence of the border, even if it’s an imaginary line on a map, it still does something to people’s sense of where they are and their identities and how they express themselves”.

This awareness of representation was one of the challenges that came with the project along with a fear of skewing a sense of border culture in the event of misrepresentation. “One of the ways we got around that”, Prof Patten told me, “was that the project didn’t just launch with no one having seen it”. She explained the team held a pilot consultancy session with people from arts, academia and policy. “It was very important to reduce the risk of that challenge by making sure a lot of people had input into the project, not just the project team”. Prof Patten also expressed the headache of being “very careful about getting copyright permission for images and text”, learning website technology, and working between two universities. Despite these challenges, Prof Patten said that the collaboration between Trinity and Queen’s ended up being one of the pleasures of the project in the end, with the opportunity to connect with colleagues and gain a wider perspective.

One of the representations that Prof Patten was particularly proud of was that of the gender and range of age of the artists. “When we started, we were just looking at a wall of photographs of male authors”, she stated. “I’m very proud that what we’ve ended up with is a much more balanced representation that not only has a balance of male and female writing but also looks at other identities that you wouldn’t think of.”

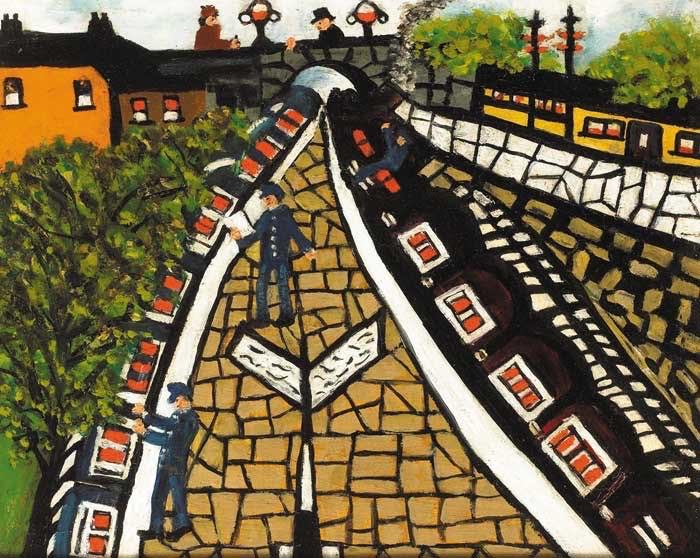

Range in the project is additionally shown in the actual mediums of the art. Though the project began by looking primarily at literature, Prof Patten told me it took her by surprise that she was so affected by some of the visual material, particularly the 20th century paintings. Of particular note is Gretta Bowen’s The Customs Examination. “It affects me because it looks like a child’s picture”, Prof Patten told me. “It renders the border as something that comes out of a child’s imagination which is so ironic because when I was looking at this, debates about the border and about customs were all flaring up in the news because of Brexit.” She explained that the childlike view of the border portrayed in the painting didn’t match what she was seeing in reality.

Along with the paintings, are the photographs. One of these is Megan Doherty’s ‘On Top of the Hill’, which shows a teenage girl in Derry, which according to Prof Patten, “prompts all kinds of questions about how much a contemporary generation that has been born since the Good Friday Agreement”.

The project, two years now in the making, is unfinished, this is attributed to a few reasons, one of which being the fact that the team wants the public to contribute by making suggestions of art to add to the archive. Additionally, Prof Patten mentioned an imbalance in the time period of the art saying, “a lot of the material is understandably from contemporary or recent culture and I really would be very passionate that we collect more material from the early decades and that needs a little bit more work.” relates to her interest surrounding how much cultural policy and funding has contributed to the sense of border culture. She explained that “it’s very difficult to do the economic archeology we need to answer the question.”

Originally pushed forward as a response to Brexit and the refocusing of the public’s “attention on the convoluted history of the border’s existence,” the fact the border itself is always changing also lends itself to the unfinished nature of the project. This is also true as it relates to the fact that the population in Ireland and near the border is continuously changing as well. Prof Patten shared that these populations are very often communities or people who have come to Ireland from countries that have their own experience with borders and partition. “We’d love to, in time, represent writing from underrepresented or quieter voices that we haven’t heard from yet,” she said.

The Irish Border Culture Project, which can be found at https://borderculture.net/, is a fascinating approach to understanding how much Ireland and its people have been impacted by border culture. Without ever forgetting or ignoring the trauma the border and violence surrounding it has caused, the project and the art that is a part of it are a deep testament to human nature and the beauty of creativity in moments of division. After all, what better to connect us than art?