While many were hoping for change in this election, it seems to have the usual hallmarks of a typical Irish election, but certainly some notable developments. So let’s get right to it, cut through the spin, and just tell you what happened.

On November 29th Ireland had a general election. For those unfamiliar, these elect Dáil Eireann, Ireland’s lower (and effectively only important) house of parliament. As a parliamentary system, this election is pretty much all that matters for determining how Ireland is governed nationally; the Seanad (Senate) is weak and dominated by the government of the day, and the President is a head of state only with few limited executive powers.

The incumbent government was an unprecedented coalition of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, Ireland’s two historically dominant parties that had never been in coalition together before, as well as the Green Party. Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael have had fewer significant differences as time has passed, they both lie in the centre right of Irish politics, but the historic divisions of the Irish civil war created this split (a longer story for another time).

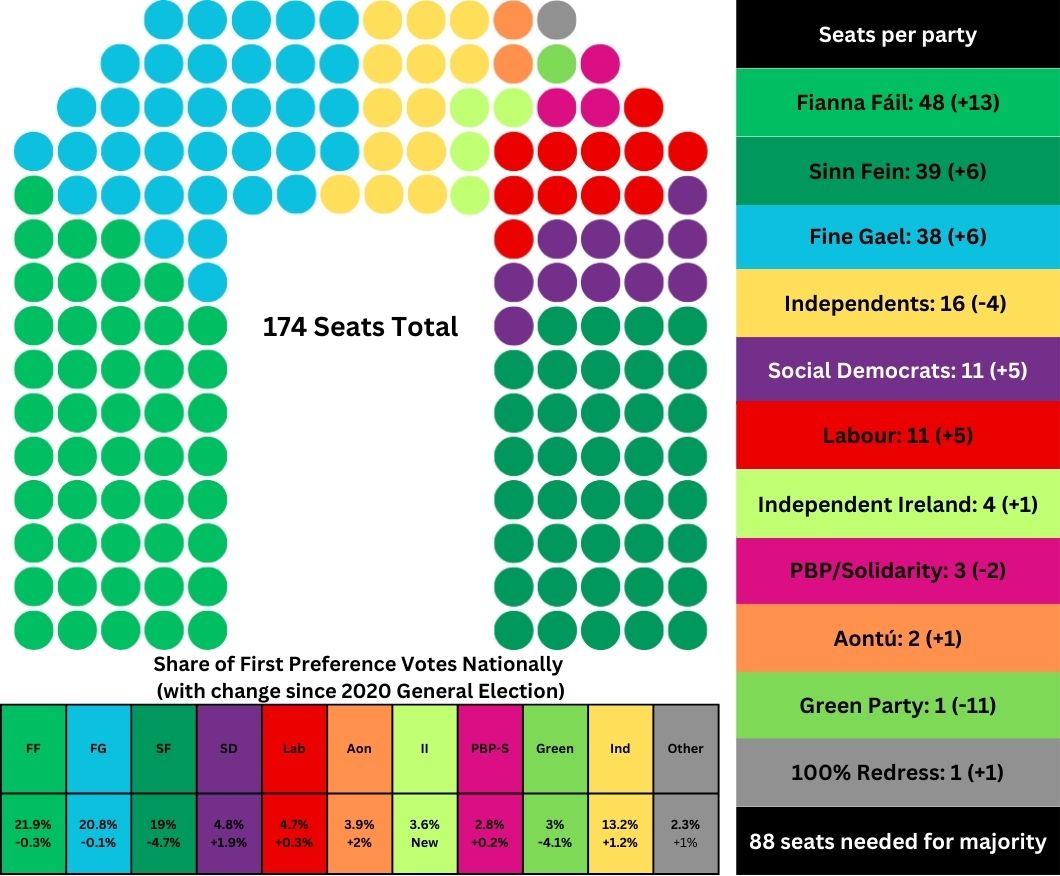

An interesting development for this election came in the aftermath of Ireland’s most recent census, which led to an expansion of the Dáil from 160 to 174 members, and redrawing of Ireland’s constituencies.

The Irish election system takes a while to fully explain but it’s pretty unique to Ireland, and essentially allows voters to rank candidates in multi-member constituencies; so elections are very local affairs but national results are close to proportional.

Going into the election the government was, unsurprisingly, hoping to be re-elected. Fine Gael in particular were setting their sights on growing their numbers, with the hope that new leader Taoiseach Simon Harris (who replaced Leo Varadkar this April) would bring “a new energy”. The junior partner of the coalition, the Green Party, were fighting for survival, facing the possibility of being completely wiped out. Junior partners in coalitions don’t usually fare well; they have to make more compromises and are accountable only to their own disappointed supporters.

On the opposition, Sinn Fein hoped to continue their momentum of growth from the 2020 election, in which they made significant gains, topping the poll nationally and being the first party to gain basically equal seats with Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael. Smaller left parties such as Labour (historically the third most important party in Irish politics, but in decline since their vote collapsed in 2016, also due to their compromises in a coalition with Fine Gael), the Social Democrats, and People Before Profit-Solidarity hoped to gain some ground and forge enough of their own path to avoid losing seats to a growing Sinn Fein, as many left parties wouldn’t have had as many seats in 2020 had Sinn Fein ran more candidates in their constituencies.

Growing alternative elements in Irish politics also hoped to make progress; Peadar Toibín’s Aontú and the newly formed Independent Ireland intended to find footing through more conservative platforms, particularly with the recent introduction of migration into the Irish political battleground.

As well as all this, Ireland notably has more independent members of parliament than all other EU countries combined. These are a variety of local figures varying wildly in personality and ideology, but it was expected that their number could grow considerably.

So, what happened? Fianna Fáil have emerged as the largest party at 48 seats; with several recent Fine Gael controversies and gaffes likely lending them an advantage over their coalition partner. With Fine Gael at 38, a likely coalition between the two parties is only two seats short of a majority, that goes down to 1 seat if they elect a TD from outside their parties as Ceann Comhairle (Speaker of the House, similar to the equivalent role in the UK). There were some upsets on the government benches, two in particular for Fianna Fáil. Minister of State for Disabilities Anne Rabbitte lost her seat in Galway East and Minister for Health Stephen Donnelly lost his in Wicklow. Donnelly was previously an independent TD, co-founded the Social Democrats with Catherine Murphy and Róisín Shorthall in 2015, but left in 2016 and joined Fianna Fáil in 2017. He became Minister for Health in June 2020, serving for the remainder of the Covid-19 pandemic

Sinn Fein emerged with 39, not necessarily a bad result but certainly not enough to hold a strong hand for a potential government formation; there aren’t enough TDs in other left parties to form one without one of the other two largest parties. The gains they would have hoped for a few months ago have not manifested.

Labour and the Social Democrats made respectable gains placing them both at eleven TDs. PBP-Solidarity has fallen to three TDs, which also means they will need to form a technical group with other TDs to retain their previous speaking rights in Dáil Debates.

The Green Party has been decimated, with only the party’s leader, Roderic O’Gorman (who replaced Eamon Ryan in June) retaining his seat.

Aontú and Independent Ireland gained 1 seat each, so some growth, but not as much as they were hoping for. Sixteen independent TDs were elected, not the wave that some pundits were predicting in previous months, though they are likely to be where the balance of power will lie. In Donegal, the 100% Redress party, founded to campaign for redress to those affected by the Mica building scandal, won a seat, and that completes our Dáil.

So, what’s next? The new Dáil will meet on Wednesday December 18th, and will first elect the new Ceann Comhairle. There is some speculation on whether the government will elect one of their own TDs, or someone else, as this will reduce their distance from a majority from 2 to 1. Once that is done, the Taoiseach will be elected, and the government effectively is formed from that point. Coalition negotiations are likely already underway.

There are a few possible outcomes, but in any likely outcome the government is led by Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael. They may work with some independent TDs to secure the necessary support to form the government and pass legislation, they have a good few to choose from, but they can be hard to predict. There is significant speculation on what Labour and the Social Democrats might do. Labour was previously a partner in every Fine Gael government until 2016, but with the party trying to rebuild many are likely wary of re-entering so quickly now that they are beginning to make progress. Party figures have indicated that they wouldn’t even consider entering government without the Social Democrats, so that they would be a stronger force overall. The Social Democrats were formed in opposition to Labour’s compromises from 2011 – 2016, so the attitude towards entering coalition isn’t likely warm, and the party have set red lines for even considering it such as having a dedicated senior minister for disability. While Sinn Féin aspire to lead a left wing coalition, the numbers simply aren’t there, and while some speculate if they will try tempt Fianna Fáil into a deal, the numbers don’t lie; the continuation of the coalition with a new third partner seems pretty much inevitable.

This was a very Irish election. We’ve got all the hits; effective continuation of the status quo, destruction of junior coalition partners, a fractured left, fun for all the family. This isn’t to say nothing happened, the realignments on the left will be important to watch, and how Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael settle into this long term partnership, and how they navigate the seat imbalance between the two, may well provide some interesting viewing.

See you all in five years, assuming this next government lasts.