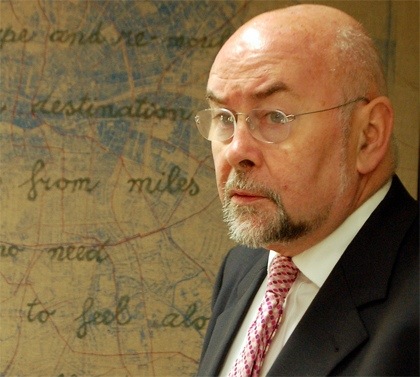

Jack Leahy

News Editor

There is a looming danger that Ireland’s economic non-sovereignty will render Ruairí Quinn’s tenure as Minister for Education a historical parenthesis: a passing interlude of regressive decisions and strategies that can be justified by their relation to an extraordinary set of fiscal circumstances.

This dynamic was broadcast on national television in September as Quinn took part in RTE’s Meeting the Minister, a brief insight into life in the department of education and skills.

The point of grabbing the media opportunity seems to have been to get across the idea that our economic mess means he has no choice but to make cuts, and every change in education is tortuously difficult to engineer.

Quinn is not the type to ask for sympathy, but he is keen to look his opponents in the eye and remind them of the various inhibitions that dominate his brief. For one thing, he has no choice but to make cuts; another, what flexibility he does have is compromised by the Croke Park Agreement and its protection of public sector employees and pay scales.

With that general theme of Irish political culture in mind, many have been reluctantly willing to forget about Quinn’s now infamous, always ostentatious election pledge to oppose rises in the student contribution charge.

The disunity that weakened last year’s Union of Students in Ireland (USI) pre-budget campaign derived its force from disagreements as to whether or not the pledge was worth students’ collective trust; in as much as Quinn was lambasted as deceptive, student leaders were decried as näive in investing so much in an electioneer’s word.

It was therefore surprising, to some, to see that the same rhetoric damning Quinn’s dishonesty will constitute a major part of the USI’s pre-budget campaign for 2013.

Much has been made of an innovative approach to lobbying adopted by this year’s officer board, and at first glance it may appear jaded and typical of the criticisms levelled at the organisation to deploy rhetoric belonging to a conversation that has long since finished.

But this is not just about the fulfilment of specific promises – this campaign has to challenge Quinn’s shoulder-shrugging neglect of third-level education, of which the pledge stunt outside of Trinity College is an obvious epitome with public infamy.

A common praise of the veteran Dublin South-East TD is that he has moved to address deep-set issues in primary and secondary education in Ireland, even if he will be forgotten by the time these reforms begin to demonstrate ample fruit. He is regularly martyred in the media and by his own words for being the fall-guy in laying a foundation, in doing so incurring mass short-term unpopularity.

The natural counter to this is that the scarce resource of ministerial time has been excessively allocated away from the problematic third-level sector. Ask the minister about his plans for students up to the age of 18 and he will talk until you insistently stop him; ask him what happens beyond planned increases in the student contribution and he mumbles a tenuous line about deconstructing regional clusters.

He has no plan for contribution and none for maintaining access, a state of affairs which is deeply concerning when you consider that he is among the most senior members of cabinet with an extremely important brief. That at least €3,000 will be asked of students registering for a third-level institution in 2015 is all he can tell you with any informed certainty about it. This is a Minister without vision; with no apparent policy preventing him reversing his previous announcements and deciding €1,000 in 2013, €6,000 in 2014.

That Ireland is experiencing financial circumstances unparalleled in its history is no excuse to ignore the most financially burdensome and complex item in his ministerial portfolio. He has demonstrated a willingness and capacity to effect long-term policy but has shunned the responsibility to do so for third-level students.

In that sense, the strong likelihood that the education and skills brief will be reallocated by 2016 at the latest is not a reasonable explanation for short-sightedness. He does not offer that excuse himself because it would be self-contradictory.

As tired as you may be of hearing about it, that pledge must be used as a tool to force Quinn to refocus on the massive problems of funding that exist in third-level education in Ireland. If he will not remain true to the word of the declaration to which he added his signature then he must take impetus from the principle and make progressive decisions for the third-level that are reflective of its needs and its potential achievements.

If students don’t ask him to do that then no one else will, and someone has to hold him to account. No matter how improbable its fulfilment may have been, it is entirely undesirable that a politician be allowed to make promises and those who believe it discouraged from publicly shaming the ensuing dishonesty. Any political leverage incurred from the spectacle of apparent support for students should be reversed in the same forum.

An apparently simple public demonstration of Quinn’s failure to fulfil an election pledge exposes his lack of long-term solution for third-level education. Knowingly baseless promises can continue to be made wantonly if no long-term policy exists in contradiction.

Whatever your views on third-level funding, it must be agreed that this cannot continue to be the case. That pledge is as relevant now as it ever was.