Every year songs are released that capture the public imagination and reflect the mood of their moment. This effect seems doubled in summer, as every year there are a couple of songs that are the natural companions to 99s, a few sunny days, and a few months complaining about the lack of good weather. It can be very pleasant to hear one of the event songs of a bygone summer and reminisce about dancing gauchely at Gaeltacht dioscós. However, for me at least, this summer’s big song—Robin Thicke’s international smash ‘Blurred Lines’, with inputs by urban stars Pharrell Williams and T.I.—contains no such simple pleasure because of the level of crude sexual objectification that it contains.

In case you are unfamiliar with the song and have missed the not inconsiderable controversy it has caused, the song consists of a series of coarse come-ons from a caveman-like character, to a woman whom he is convinced is sending mixed signals – these are the ‘blurred lines’ of the title. Though she may be a ‘good girl’, he knows that ‘you’re an animal, baby it’s in your nature’. Her last lover was a wuss; he didn’t ‘smash that ass and pull your hair’, while Thicke claims he will give her ‘something big enough to tear that ass in two’. He knows, as the chorus insistently blares out, that ‘she wants it’, as if suggesting that no woman could resist his leery passes.

“Misogyny in popular music is nothing new; it is all too present”

Though ‘Blurred Lines’ can be accused of many things, subtlety is not one of them. In the uncensored version of the music video, Thicke and co. drool, fully clothed, over a trio of topless women. The fact that the song has been so massive a hit—at the time of writing, 152 million YouTube hits and counting—is at best an indication of how much three men can get away with in the name of a catchy tune, and at worst a mark of just how much misogyny still lurks in the minds of some men.

Thicke’s attempts to defend himself from critics have been risible. He claimed on The Today Show that the song is ‘a feminist movement in itself’ because of the line ‘that man is not your maker’. It seems to have escaped his attention that this line is a reference to the woman’s ex and is part of the singer’s strategy to belittle and dislodge him. Even without this slimy ulterior motive, a defence based on one inoffensive lyric in a song full of offensive ones is utterly unconvincing. Thicke’s second line of defence has been to plead his past good behaviour in the matter of misogyny. In an interview with GQ, he said of the video: ‘what a pleasure it is to degrade a woman. I’ve never gotten to do that before. I’ve always respected women.’ Citing his status and that of his collaborators as married men with children, Thicke insists that he and his mates are ‘just three really nice guys having a good time together’. This is linked to his final attempt at rationalisation, which has been to suggest the song is a joke and that it should be taken as such. In support of this, he has named Benny Hill as the influence behind the song’s video, to which I can only say that if you’re reduced to name-checking Benny Hill to defend yourself from charges of sexism, it must be time to put up your hands and plead guilty.

“A contemporary musician would never allow himself, or be allowed, to pen racist lyrics and then to shoot a blackface pastiche for a music video”

That said, misogyny in popular music is nothing new; it is all too present in heavy metal to hip-hop in particular. Flicking through the book Fear of Music: The 261 Greatest Albums Since Punk & Disco, I was struck by comments author Garry Mulholland made about The Beastie Boys’ 1986 debut Licensed to Ill and how they ring true in relation to the popularity of ‘Blurred Lines’. The album’s lyrical content caused widespread controversy against the backdrop of a new musical landscape ruled by ‘the youth dollar and an increasing reliance on glibness disguised as irony.’ Referring to the brattish lyrics, Mulholland asks ‘surely if you make blatant the fact that you are skinny young wimps who could never cause the girls ‘n’ guns mayhem within the lyrics, everyone will get it, right?’ He goes on to refer the incident at the 1998 Reading Festival where The Beastie Boys criticised The Prodigy for performing ‘Smack My Bitch Up’, how they ‘didn’t appear to see any irony whatsoever’ in this and helped make the subsequent popularity of that song ‘inevitable by convincing us that misogyny in pop music was big and clever.’

If this is indeed the case, it goes some way to explaining the enormous popularity of ‘Blurred Lines’. As a fan of both heavy metal and hip-hop, I’m familiar with many lyrics equally objectionable, if not more, than those of Robin Thicke. However, I think I took exception to the way the song takes serious issues and, after wrapping them up in irony and laddish ‘humour’, supposedly turns them into a bit of harmless fun that it’s perfectly acceptable to like. Clearly enough people have been willing to look past that to make the song’s composers a great deal of money. In late July, the song broke an eight-year-old record for radio audience, with 242.65 million listeners beating the figure for Mariah Carey’s ‘We Belong Together’.

In his Today Show interview Thicke says that ‘great art’ should ‘make us talk about what’s important and what the relationship between men and women is’. Great art should indeed do this, but Thicke’s is nothing of the kind. It offers instead a dangerous and debased depiction of love and sex. While the hype around the song may have died down somewhat since its release in late March, its ubiquitous nature has been made all the more discomfiting by recent high-profile sexist incidents.

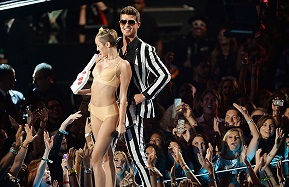

Since ‘Blurred Lines‘ charted in Ireland, it has been the soundtrack to, among other episodes both domestic and international, Fine Gael TD Tom Barry’s ‘horseplay’ in the Oireachtas, the spew of rape and death threats sent to feminist activist Caroline Criado-Perez via Twitter, and the highly publicised ‘Slanegirl’ photos and subsequent internet furore. Songs like ‘Blurred Lines’ underline the belittling attitude and double standards held against women in many sectors of the media that has become worryingly normalised in contemporary society; it comes as no surprise that, after their controversial duet at the recent VMA Awards, Miley Cyrus, not Robin Thicke, has been the target of internet ire.

A contemporary musician would never allow himself, or be allowed, to pen racist lyrics and then to shoot a blackface pastiche for a music video. This analogy throws the outrage generated by ‘Blurred Lines’ into sharper relief, and shows how far we have to go before relations between men and women are consistently treated in a mature way in popular music.