Fionn Rogan | Deputy Opinion Editor

Whilst Ireland may have shirked off its saintly aspirations in recent years, it appears determined to preserve its scholarly ambitions, when perhaps, really, it should stop. Renowned for its well-educated workforce, Ireland has the second best qualified young people (25-34) in Europe with 41.6% of this demographic boasting a third-level degree. Whilst Cyprus is in first place, the European average is 29.1%. However, one has to consider what, exactly, the intrinsic value of a third-level degree is, especially now that unemployment rates amongst graduates are creeping ever skyward. Does a third-level degree have any value, or does it just serve as a reminder that you happened to spend three or four years travelling to and from a college you thought you might like back when you were 18? Did you actively and consciously decide back in your Leaving Cert year that ‘yes, I do want to go to third-level so as to continue my studies’? Or, like a great deal of Irish students, did you find yourself being herded into the third-level system because that was the natural progression from secondary school, and, as a college graduate, you would become a symbol of a well-adjusted and progressive society?

One must ask oneself the vital question; ‘Are there too many college students in Ireland, and has the exercise become entirely unfeasible for the state to finance any longer?’ As the beneficiary of a highly discounted third-level education, I can certainly see how unattractive the question might be on a personal level, but within the context of the nation as a whole, its merit soon becomes apparent.

This year, there are one hundred and sixty thousand full time students studying in one or more of the thirty-eight higher education institutes in Ireland. Approximately twelve thousand of them will drop out of college this year. Statistics suggest that one in three students in Dublin institutions will drop out. ITs will see less than 80% off their first year class progress to second year, whilst universities will ‘bid adieu’ to 9% of their Junior Freshmen. The Institute of Technology Tallaght (ITT) has even recorded dropout rates of more than 50% in courses such as tourism, hospitality and sports & leisure in recent years.

There are several reasons for the grossly high dropout rates amongst third level students in Ireland. Cost is often presented as the primary factor in the case of dropouts, and while this is, of course, a legitimate reason, I would suggest that a more influential reasoning in a number of cases might be that that student should never have been in college in the first place. Some might regard this claim as elitist, but that only holds true if you believe that a third-level education is the highest accolade one can achieve. I would argue that it is not, and that college is not for everyone; in fact I would go so far as to say it isn’t for most, at least, not in its purest form of true academia. The truth is that Irish third-level institutions have spread themselves too thinly upon the ground by continuing to offer and develop courses that are of no earthly gain to anyone nor the economy, or courses that realistically have no place in a college setting. Professions that traditionally employed on the job training are now clogging the colleges up with courses that are leading to ever increasing waste within the system. If one goes back to the 1980s, Nursing was such a course, where trainee nurses would be trained within the hospitals, and not in colleges. This setup appears to be a more logical one, as surely the longer a trainee nurse can spend in a practical hospital environment, the better their preparation for becoming a nurse would be? By training within the hospitals, trainee nurses were also spared the headache of student contribution fees, registration, and inept timetabling issues, while the colleges were saved from difficult administrative duties and the expense needed to actually train a nurse for whom a job could not be guaranteed.

I would argue that it is not, and that college is not for everyone; in fact I would go so far as to say it isn’t for most, at least, not in its purest form of true academia.

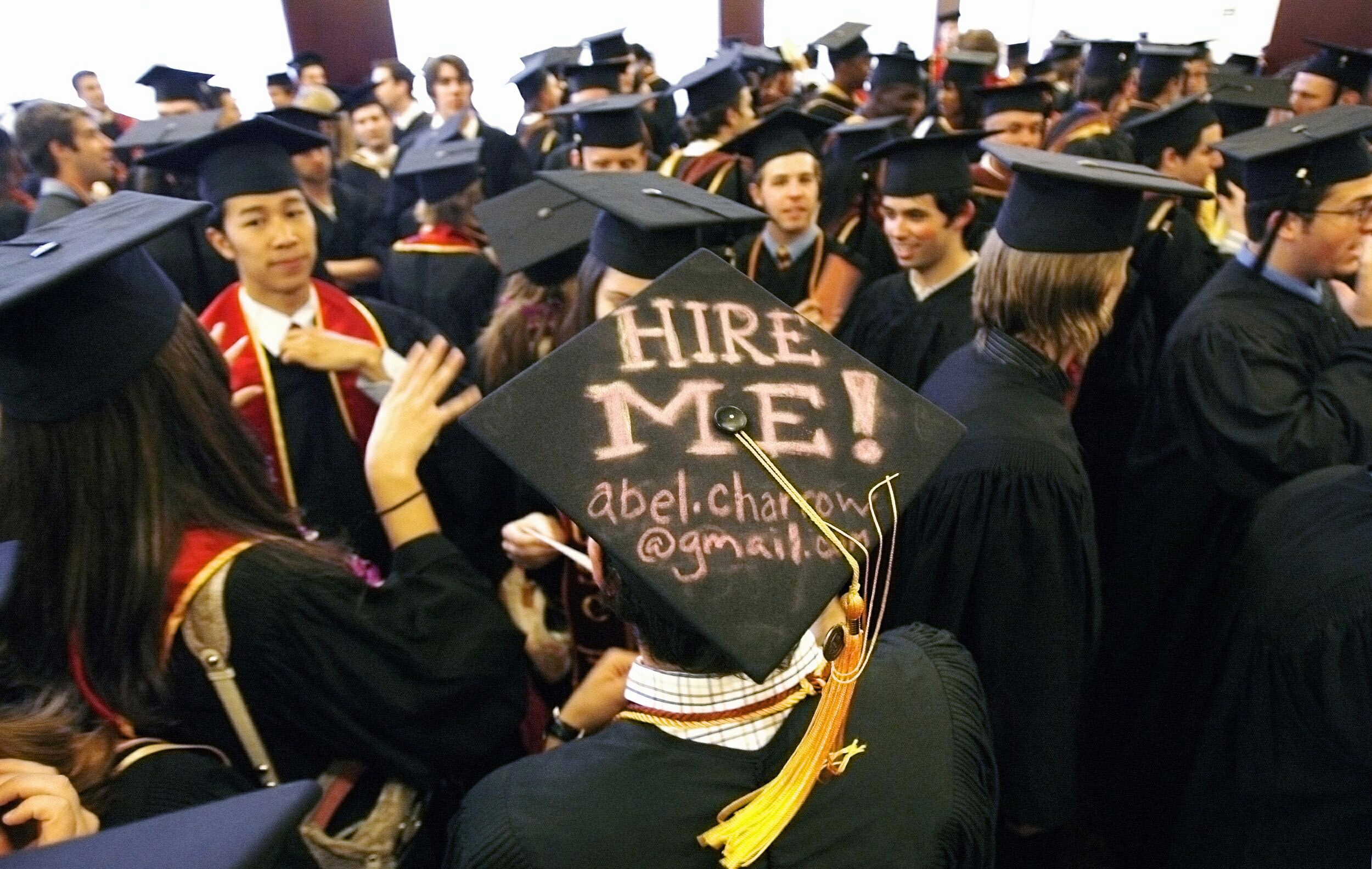

Third level education is starting to be perceived as a right rather than a choice, and while some may argue that free third level education for all is the moniker of a truly advanced and egalitarian society, I would suggest that we have wrongly prioritised it and in doing so we have diluted any practical gain it could have provided to the country. Third level has become the natural next step for Leaving Cert students, and some may view it as the only step, when, in fact, it is perhaps the most limited of all the possible next steps. Secondary school students fail to recognize the potential for travel, apprenticeships and even entrepreneurship, feeling that they cannot attempt such things without the supposed security of a degree. Our economy needs a revitalized manufacturing industry in order to kickstart it once again, and, ultimately speaking, that industry does not need several thousand graduates with a masters degree in twentieth century US literature – they need people with practical manufacturing skills.

The solution to our problem of hyper-education involves large investment in vocational education, a societal re-evaluation of our primitive notions of vocational training and a streamlining of our third-level institutions. There is no point in saying less people should go to college if we don’t provide an alternative path. By investing in vocational education we are actively declaring that we feel students should be provided with a means to acquire actual practical skills that we, as a society, will value and benefit from. Being able to write a feminist critique of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise is admirable, but only in the eyes of a select number of academics – it is ultimately useless to the Irish society and economy as a whole. However, investing in vocational training is moot if we do not tackle the regressive perception of vocational education as being inferior. We need to overhaul the societal paradigm that dictates this damaging opinion by creating high-class vocational institutions that mirror the prestige of third-level institutions.

Finally, we must streamline the colleges. Access to third-level education should be restricted to no one on the grounds of finance. Admission should be based entirely upon interest in a chosen topic and success in examinations. Irish colleges should become a hotbed for pure academia and intellectual pursuits without the distraction of employment opportunities after graduation. Ideally, students would pursue a career in academia. Those not interested in such a career can be catered for by the state’s new vocational schools. We achieve this by reintroducing fees and adopting the UK Tuition Fee Loan system, whereby students do not start paying back their loan till they have graduated and are earning over £21,000 a year – even at that stage the repayments are miniscule. The loan scheme mitigates the rich/poor divide by placing every student on a more equal setting. Fees also serve as a deterrence, meaning that only those who are fully and entirely committed to academia will consider progressing to third-level, which will ultimately reduce the level of dropouts and improve efficiency within Irish colleges.

The Irish have developed an unhealthy obsession with education in recent years, and it has come to the detriment of our economy and our values. We have overvalued unproductive education and have thus created a hyper-educated, but, ultimately useless, or, perhaps, skill-less population. So we must ask ourselves, ‘should I really be in college, or are there better things I could be doing with my time right now?’