Charlotte Ryan|Deputy Features Editor

In the type of education the majority of us will have received, the activist always came first. Be it because, as children, we were too young to understand the complex strains of thought at play when we learn about history or because every kid loves a superhero figure to root for, the names of the men and women who fought the battles of society were always those that lingered longest. Their Batman symbols were the grainy black and white pictures we saw in history books, whether it be Rosa Parks resolute in her bus seat or Martin Luther King Jr.’s sad eyes gazing out over a devoted crowd.

These colossal figures made protesting seem like a calling, yet today it is immersive in our society. From Facebook posts and Twitter hashtags, to personal blogs and the walls of bathroom stalls, protesting has pervaded our interactions in ways most of us aren’t even aware of, making it easier for passionate thinkers to find a platform.

College students have often been on the ground for significant political and social movements and, with all our enthusiasm and caffeine problems, we’re the ideal protesters.

College students have often been on the ground for significant political and social movements and, with all our enthusiasm and caffeine problems, we’re the ideal protesters. For almost as long as universities have existed so have student protests. One of the earliest examples of the student protest occurred at the University of Paris in March 1229 when, following a rowdy night of drinking during the carnival of Paris, a dispute broke out between a group of students and the tavern owner. Despite the students being protected by the ecclesiastical courts, the university authorised the punishment of the students. This decision led to enormous protests. The unease lasted two years, the end result being a number of student deaths and the independence of the university from local authorities.

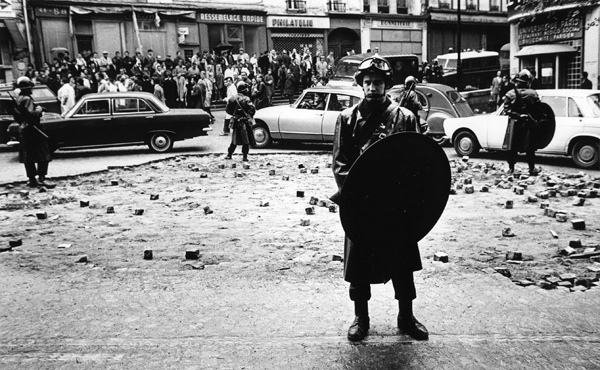

Paris was the setting of another historic series of protests. In May 1968 protests kicked off after the closure of Nanterre University in Paris which came after months of conflict between the administration and far-left student groups. In response to the closure, some 20,000 protesters marched to the University of Sorbonne, and were met by startling police brutality. This heavy-handed response by the government sparked country-wide protest, which at its height virtually brought the entire nation to a standstill.

While the May ’68 riots succeeded as a “social revolution, not a political one”, as stated by Alan Geismar, one of the leaders of the protests, it proved that powerful student-led political reform is possible and has merit. The protests currently ongoing in Hong Kong are a perfect demonstration of this. Organised by Occupy Central and the Hong Kong Federation of Students and Scholarism, what started as a sizeable group of students protesting the proposed restrictions on electoral candidates in the 2017 election has grown to include tens of thousands of pro-democracy supporters as well as the thousands of global supporters witnessing one of the most extraordinary and significant political movements in recent history. These student-led movements are testimony to the fact that, when young people are educated, opinionated and, most importantly, passionate about a cause they have the clout and strength in numbers to elicit real and lasting change.

These student-led movements are testimony to the fact that, when young people are educated, opinionated and passionate they have the clout and strength in numbers to elicit real and lasting change.

Contrasting the peaceful and systematic form of protest that has been so integral to the success of the Hong Kong student uprising are the more extreme and radical examples that have peppered history. Following the kidnapping of 43 teaching students by local police in Iguala, Mexico and the subsequent discovery of mass graves containing what are largely believed to be the charred remains of at least some of the victims, frustrated locals took to the streets to burn government buildings in retaliation. While the anger fuelling the move is justified, the violence of such acts merely exacerbates the mounting tension and fractures trust between the sides. Even more extreme is the practice of self-immolation as protest, as done by Kostas Georgakis, a Greek geology student studying in Genoa, in 1970. The act was a demonstration against the dictatorial regime of Georgios Papadopolous, head of the Greek junta that ruled the country from 1967-74 and, while tragic, served little purpose other than to rid a political oppositional movement of one of its fighters. It’s evident that for a student movement to carry any weight the protesters must act responsibly and avoid being cast as the overeager reckless rabble rousers.

It’s evident that for a student movement to carry any weight the protesters must act responsibly and avoid being cast as the overeager reckless rabble rousers.

Of course, this kind of more radical student activism isn’t exclusive to just a few countries. Trinity has had its fair share of radical protests and demonstrations that push at the boundaries just enough. On V-E Day, May 7th 1945, fifty students scaled to the top of Regent House and strung up a Union Jack in celebration of the Allied victory. Hearing of this, a group of students from UCD stormed down to College Green to remove it and clashed with the Trinity students. Also punctuating our history are what can only be called the urban legends of Trinity, such as the tale of a group of Phil members that murdered the Junior Dean over a dispute.

Myths and rumours of murder aside, Trinity’s track record for fostering student activism has been rocky in recent years. In a rally organised by the Union of Students of Ireland (USI) in 2011, which addressed government plans to cut the student maintenance grant, 1,000 Trinity students marched through the streets in protest. However, at another rally in 2013 there only marched 25 students, an embarrassingly low amount. Even in the most recent of marches on October 8th between 250 and 300 students participated – a definite improvement, but not enough of one for us to be satisfied. So how do we fix it? Do we point fingers at the USI for lagging in their organisation? At the student body for simply not caring enough? Do we shake our fists at a society that would sooner accept disillusionment rather than demand change just because it’s easier? If the mentioned successful protests are anything to go by, it’s pretty simple: get educated, get angry, and get heard. The rest will be history.

Sign Up to Our Weekly Newsletters

Editors' Picks

Behind the Scenes with Gaza’s Medical Staff

“Forever Chemicals” No Longer: How France Plans to Ban PFAs – and Why We Should Follow Suit

An April Fool’s Joke with Meaning

The Fall of American Hegemony: Trump’s Policies and the World in Crisis

An Open Letter to the Students’ Union