Aisling Curtis | Senior Staff Writer

Conversations about the Marriage Equality referendum and the potential turnout of the fabled “youth vote” have saturated news and social media outlets, and will likely continue to as we move into 2015 and the day draws ever closer. But for me, and the thousands of others who are currently not in the country, we might as well put our hands over our ears and pretend it isn’t happening. Choosing to study abroad this year means I won’t get a vote in May.

Theoretically, of course, I’m still on the voters’ register. I like to think someone, somewhere, will be eagerly expecting my ballot on the day. But the Irish government has refused to implement a system for expats to vote in Irish elections that doesn’t involve flying home, a clearly unfeasible course of action most. Unless I magically become an Irish official on duty abroad – or their spouse – there is no postal voters’ list for me, or for any other Irish person who does not currently reside in the country. Though I am only gone for nine months, I am apparently no longer afforded a say.

Unless I magically become an Irish official on duty abroad – or their spouse – there is no postal voters’ list for me, or for any other Irish person who does not currently reside in the country.

It’s a situation that’s become increasingly aberrant on the international stage, where more than 120 countries have given their expats a vote, and only 62 – including North Korea – have not. Last year, the European Commission released a stinging criticism of Ireland’s “disenfranchisement” of its emigrants, inspiring a comprehensive Oireachtas report that agreed with this assesment. In response to these empathic recommendations the government is doing its usual aimless shuffle: mumbling about a possible referendum “next year” (in which we will presumably not be able to vote), citing fragile concerns of the definition of citizenship, time limits, reserved seats, and a fear of disproportionate effect from expat voting when coupled with a minuscule turnout. Such ineffectual blithering will likely push any resolution back by years. In the meantime expat voting will continue to be seen as a complex and divisive issue in Irish politics.

And yet Ireland is an anomaly in a sea of agreement. The arguments put forward against allowing expats to vote – “no representation without taxation,” concerns that they will skew voting, fears that it could delay the process – are unfounded, and cause no trouble elsewhere. Those living abroad generally vote at the same rate as those at home, and a properly run process would not need to cause delays. As for the taxation argument, many of those abroad still have links to the country, and pay taxes as a result. And that aside, the argument is still shaky, considering that no other country seems to think that expats should be taxed in order to allow them to have a say.

For a country with such famously high emigration rates, it seems petty and cruel to force those, already losing friends, family, and the community where they grew up, to lose a say in the political process too. For many, emigration is a forced consequence of the shoddy decision-making current and past governments. Many of those same people long to return to a more stable Ireland years down the line. Depriving those who have suffered from governmental shortcomings a say in future leadership seems like a reaction borne of fear, as if they’re worried that the very expats that they have forced out of the country might seek revenge if given a vote.

Ireland is an anomaly in a sea of agreement. The arguments put forward against allowing expats to vote are unfounded, and cause no trouble elsewhere.

Although I don’t necessarily agree with giving a vote to somebody who has been away for 30 years and has no intention of returning, many countries have limits of 5 years that would not skew the voting in a major way. Students abroad for the year should clearly be allowed to vote, and would be able to with a 5 year limit. Young people who have emigrated to find work could still contribute to the very political process that sent them abroad. Older workers supporting families still in Ireland, would have a sense of purpose, a feeling that they still belong to the country where many of them grew up and retain strong ties.

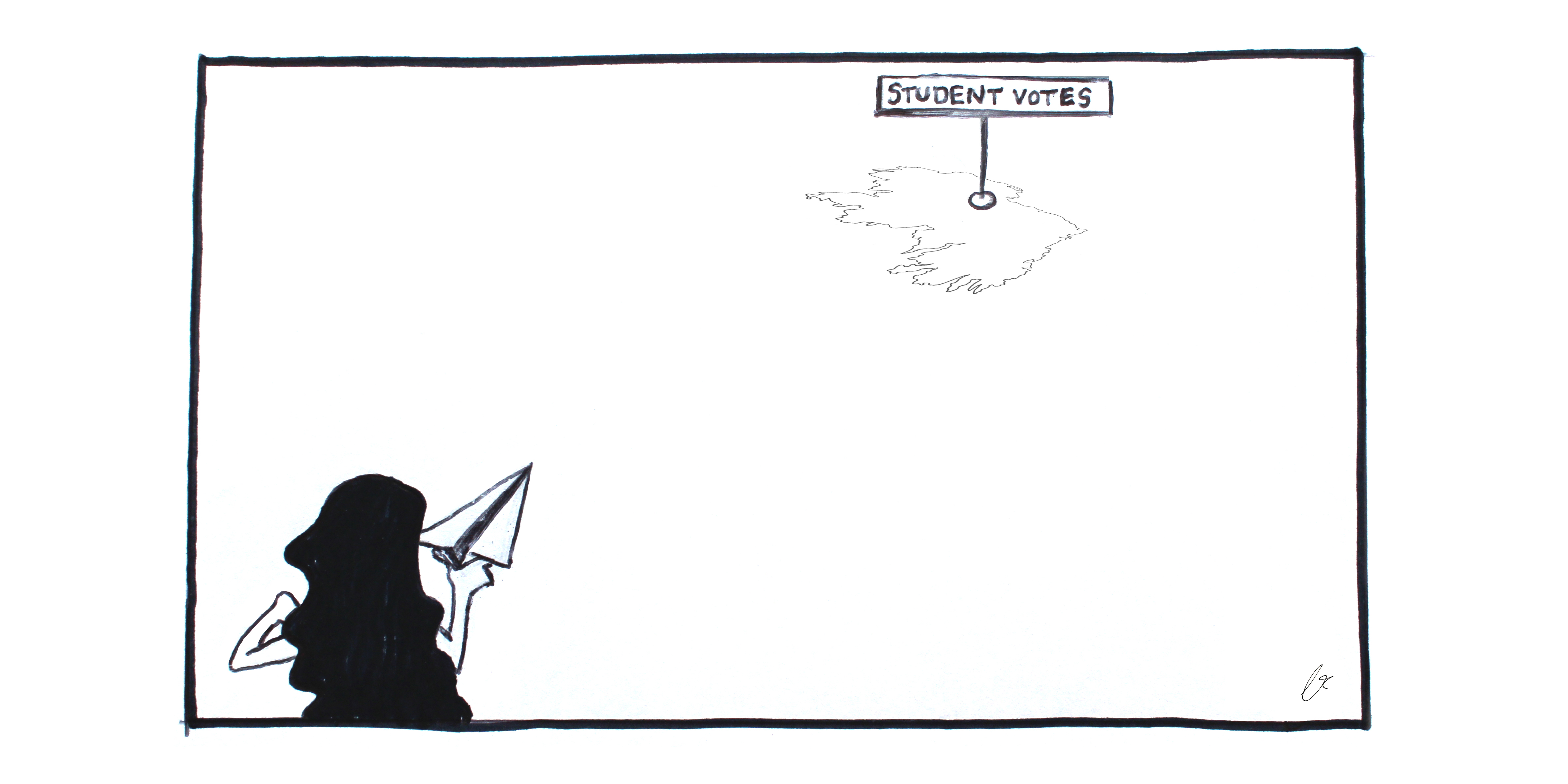

I cannot vote in French elections. I haven’t been permitted to swap an Irish vote for one here. So while abroad I am politically voiceless, with a foot in two different countries and no say in the politics of either. I want to vote, and many other young people want to vote, and many emigrants who intend to return want to shape the country for when they do. But apparently I’d be better off doing what everybody thinks young people already do, and just sticking my head in the sand.

Illustration by Ella Rowe for The University Times