Seán Healy | Senior Staff Writer

Romance is our selfish loophole. It can occasionally allow us to indulge at the cost of another in an unquestioned way. In the name of ‘love’ is an argument of heavy weight to most today – created and maintained by media that predominantly portrays love as an economy of two people each seeking their own best ends.

The half with the most obsession and infatuation, displaying the greater portion of ‘love’, is to be pitied, say the books, movies and poems. The sensitive obsessed read, watch, comprehend or misunderstand, and act accordingly, with selfishness unknowingly appeased and protected under layers of literature and culture. I have done things thinking I’ve done them for love, but I must stress and admit that it took me a long time to admit it to myself: I am an unloving person in the romantic sense.

Put down your romance novels if you’re just going to skim through them blindly, because obsession is not love, and effort does not entitle anyone to enter a one-sided relationship.

If I love someone, shouldn’t I be content if they use their freedom to diverge routes with me towards happiness and their desired life? I may have looked at Yeats’ line, as a teenager, and shuddered with familiarity on hearing it, “Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.”

Now, I reflect cringingly on my adolescence not seeing the ugly, selfishness of the poem – Yeats publicly professing to Maud Gonne that she should live her life somewhat catering for his feelings as a sensitive poet reflecting on his own dreams. Yet Yeats was so ‘in love’ with Maud, that he ignored her refusal to his proposal three times then shifted his attention to the next best thing – her daughter. This is not love, it’s obsession.

Yeats doesn’t love, so who does? “What is love?” It’s difficult for me to answer that in my own words. I can use examples, but I’ve stopped saying that I know what the real phenomenon is. Many people believe they know what it is, but hold no accurate idea beyond ignorant associations with traditional descriptions. Some great films and fiction covering this widespread obliviousness owe their success to a largely oblivious audience.

Vladimir Nabokov is seen by many readers as a writer of love and a controversial man for the unusually flattering image of paedophilia in his masterpiece, Lolita. His story, about a soft-spoken academic who becomes infatuated with a prepubescent girl, many would view as an argument towards the universality of romantic love. In opposite fashion to Yeats, the book’s protagonist/antagonist, Humbert Humbert, marries the Mother to remain close to the child, and throughout most of the novel, his desires are adamant, even trying his luck with an older Lolita when she reluctantly reaches out to her estranged step-father for financial aid.

If I love someone, shouldn’t I be content if they use their freedom to diverge routes with me towards happiness and their desired life?

The genius of Nabokov is not his unfalteringly romantic writing, but his ability to lead the audience to realisation through giving the most distorted view possible of what is manipulation and rape – even assigning Humbert as the narrator for the novel. His only fault was forgetting that people must allow realisation. Time has proven that readers of Lolita must be listening to learn, even while they read about a man soliciting sex from someone of whom he is a guardian, even while reading about a man making advances towards his recoiling step-daughter, even while reading the typical arguments, eloquently veiled, but indeed typical, of a rapist.

Nabokov didn’t extend his critical view of some ‘loves’ to the population of those who would read his novel. He never expected that so many could be so similar to Humbert in denial, favouring an attractive notion of infinite affection over seeing the underlying horror of the text. He didn’t write ‘love at all costs’, he wrote about a man’s obsession and how it ruined the life of an innocent girl.

(500) Days of Summer is a contemporary anti-romance rom-com. The film alleviates the fault of some anti-romance media by omitting the mystifying factor of ‘forbidden love’ from the story, and if that isn’t enough, the creators also state in the first sentence of the film, “This is not a love story.” The film centres around Tom, a writer at a greetings cards company. Tom has no stated disorders, but he portrays similar obsessive infatuation as that described by Nabokov.

Nabokov didn’t write ‘love at all costs’, he wrote about a man’s obsession and how it ruined the life of an innocent girl.

Summer, Tom’s love interest, hints to Tom that she loves Ringo Starr because nobody loves him. She scrutinises Tom after he states that if it were up to him, he would make people see the beauty of architecture. She satirises traditional relationship behaviour in IKEA kitchens. Summer later explicitly states that she just wants friendship. She says, “We’re having fun,” “Nothing is happening.” Summer tells Tom about her emotional issues preventing her from easily entering romantic relationships. Tom ignores all of this, and pursues his selfish escapades that eventually cause Summer great emotional discomfort. By the end of the film, Summer has changed work and moved away from all her friends there – the same scenario that opened the movie. We witness a split-screen scene where we get a glimpse of Tom’s vanity deluding him into overlooking sentiments unshared.

Most look on, and just like some readers of Lolita, only allow themselves to take from it what their grudges and beliefs allow of them. Some comments commonly heard on fanmade YouTube videos: “That girl’s behaviour was very selfish,” “What a bitch!” “She doesn’t deserve him.” Many see Tom as deserving Summer’s affections. By shining a light on this unspoken, yet still vastly accepted, theory of entitlement, (500) Days of Summer is much more than a cute story of “boy meets girl”.

I first would have enjoyed the film as a piece of satisfying comfort-cake. But I eventually stopped using terminology like “the friend zone” or “nice guy, bad guy”. There’s no such thing as the ‘the friend zone’. It may be a feeling often observed that you can’t escape your platonic place in someone’s social circle, but to blame it on an abstract thing like a ‘friend zone’ is juvenile.

This self-diagnosis of ‘friend zone’ is primarily observed as a male thing. Women are kind by nature, we say, but when a man does something nice, this is special, so we are ‘entitled’ to something. I’d argue it’s why men more often approach women to buy them alcohol at the bar, why Tom felt so entitled to a relationship for being nice to Summer and accepting her playfulness without argument, why so many men, who incorrectly view themselves as caring, curse the strengthening modern ability of sexually compatible people to just be friends.

If being a nice guy is a romantic dead end, then you, questioning your acquaintance’s judgement and authority to make her own choices, judging from outside the relationship, need not worry.

Friendship shouldn’t be viewed as a currency in need of repayment by means outside of itself. I accept that some male friends are mostly troubled by their female companion’s choice of ‘bad guys’ over ‘nice guys’. If being a nice guy is a romantic dead end, then you, questioning your acquaintance’s judgement and authority to make her own choices, judging from outside the relationship, need not worry.

What you’re feeling in ‘the friend zone’ as ‘a nice guy’ is not a stabbing of unspoken love, it’s the self-enforced karma of vanity and, hopefully, a harsh but heard lesson on the place of old ideas in a modern setting. Put down your romance novels if you’re just going to skim through them blindly, because obsession is not love, and effort does not entitle anyone to enter a one-sided relationship.

Perhaps decades ago if you were nice to a lady and dowered a few cows, you’d get your lifetime of sex. But seeking that something extra and feeling grief when you fail does not mean you ever came close to finding it. Feeling selflessly happy for someone… find that and perhaps you can sing to the birds in the trees about your newly acquired skill, as the character of Tom did at the end of (500) Days of Summer.

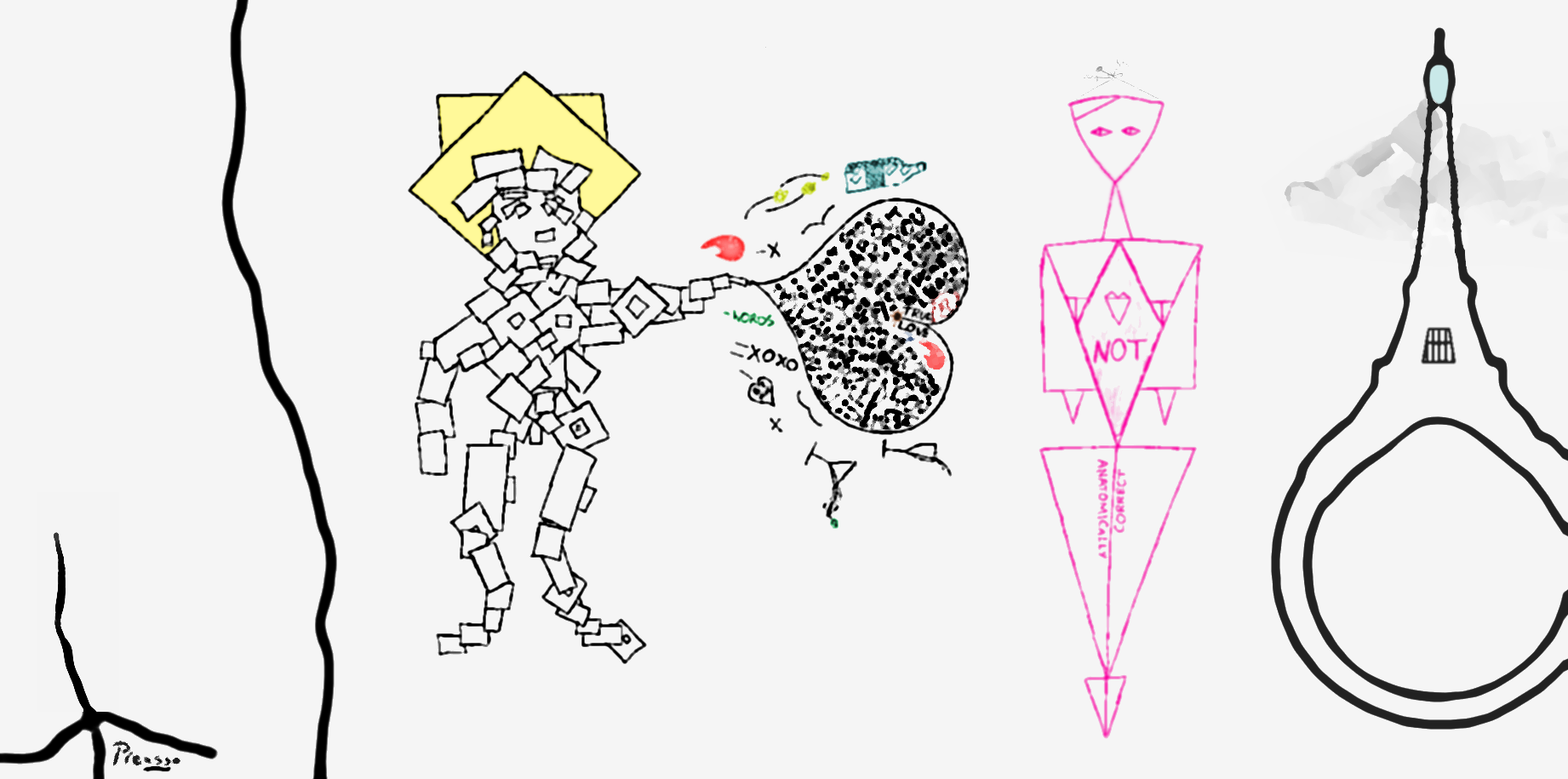

Illustration by Seán Healy for the University Times