The world of student politics is a multifaceted one. At every Freshers’ Week across the country, there is a guarantee of a strong presence from the student societies of every major Irish political party, searching for new blood to join the ranks. Yet, with an undergraduate degree at Trinity often lasting less than a term in the Dáil, what is it that encourages students to engage with a political party or society during their short time at the university?

Naturally, there are many stereotypes one can throw at today’s student politician. They are a CV-builder, cannon-fodder for party lobby groups, deluded by impossible ideals and pursuing a future tenure as Taoiseach. For a university that has yielded several Presidents, a shower of TDs and the occasionally revolutionary (yes, Mr. Tone), it is perhaps surprising that Trinity’s political societies attract these jibes. Perhaps it is something reinforced by wider stereotypes of the modern politician in general. With so many contentious political issues in Ireland, such as water charges and the debate around repealing the eighth amendment, is it really attractive to be a politician, to stand at the forefront, defending claims in the face of a tirade of heckling and harassment?

However, within the Trinity branches of political parties and societies, a very different voice can be heard, and it’s trying to dispel these claims. Many within these societies aim to offer a more realistic picture, driven by open debate and discussion rather than reluctantly offer new members the first rung on a botched political ladder. Political involvement at university is not an exclusive rite of passage for those entering law or politics. Instead it appeals to practically every discipline within campus, not only a space for people to discuss their political ideal, if they have one, but to get involved in larger communities that stretch beyond Trinity’s Front Gate.

Many within these societies aim to offer a more realistic picture, driven by open debate and discussion rather than reluctantly offer new members the first rung on a botched political ladder.

This is the case for Tamsin Greene Barker, a second year student of Philosophy, Political Science, Economics and Sociology (PPES) and current treasurer the Trinity Labour Society. Speaking to The University Times, she explains: “I got involved to learn and meet people with similar attitudes. When I joined, it didn’t cost much and the people there made me feel welcome”. She stresses the distinct nature of a student party, which sets it apart from other student societies, adding that youth parties “are different to academic politics – there’s no pressure and you can learn at your own pace. We’re there to engage and learn.”

Barker rejects the idea that youth wings are just lobby numbers: “At our meetings we can interact with the head of the youth branch [of Labour], who has a direct line of communication to the party. If there’s something we want to put forward, they can help”. Naturally, as with any student society, people strive to stand for top committee roles, but Barker insists: “From my experience, [Labour Youth] is not overly hierarchical, the top positions are functional and responsibility is shared with anyone who wants to get involved”.

Of course political parties themselves are by no means the only option for students who wish to get involved in politics. Sam Johnston, a third year PPES student and committee member of Trinity Politics Society, believes that the society offers a fair alternative for those who don’t want to opt into the ideas of a party. Speaking to The University Times he asserts the society is “good for watching it all unfold. Joining a political party depends on whether you’ve found one you really like, and can feel comfortable in ideologically.” Instead, “PolSoc offers the space to be cynical about the state of politics from the sidelines”.

Indeed, one can actively participate in student politics without becoming involved in a party in many ways. Trinity Politics Society offers an opportunity for those who do not wish to align themselves to any particular group to quiz the student parties. The society recently hosted a multi-party debate among the youth wings which Barker’s Labour group attended, along with representatives from the other major Irish parties. “There’s no obligation to join a party, and the multi-party events offer a great platform for healthy debate” says Barker.

Both Barker and Johnston maintain that, regardless of political affiliation, involvement with some form of politics in university is undoubtedly a good thing. “It helps you engage critically with society, and makes you think about the type of society you want to live in. From an employment perspective it helps develop your communication skills too” says Johnston. Barker agrees: “It’s not necessarily a direct route into a political career, but it can be used as a stepping stone. Students have a great opportunity in front of them and I would definitely recommend getting involved.”

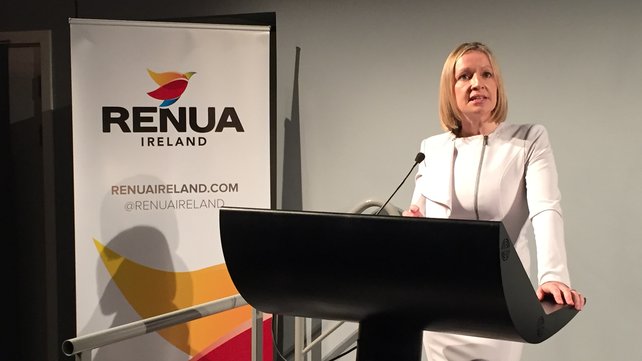

Being a smaller party on campus isn’t easy, as Renua discovered when they struggled to reach the 200 required signatures to form a society.

Essentially, being a part of the political life of Trinity offers many benefits to its participants in the face of its critics. Those involved would argue that there are many opportunities for anyone with, or even without, a sustained political opinion to get involved, satirise, campaign or critique within the societies available. However, being a smaller party on campus isn’t easy, as Renua discovered when they struggled to reach the 200 required signatures to form a society. With all the major political parties maintaining a strong presence at Freshers’ Week, and with other ways to get involved in social issues, breaking through as a new party and getting enough students excited can be difficult.

Yet, if anything, the sustained presence of these societies on campus indicates a consistent political interest from new and existing students, or at least a group of those students. And, ultimately, when it comes to politics, associating in a collective with people who share a common ideology can be a rewarding experience, creating friends and contacts, and perhaps as well as a critical perspective one may not have considered before. The question may not be who gets your vote, but who you’d like to get to know.