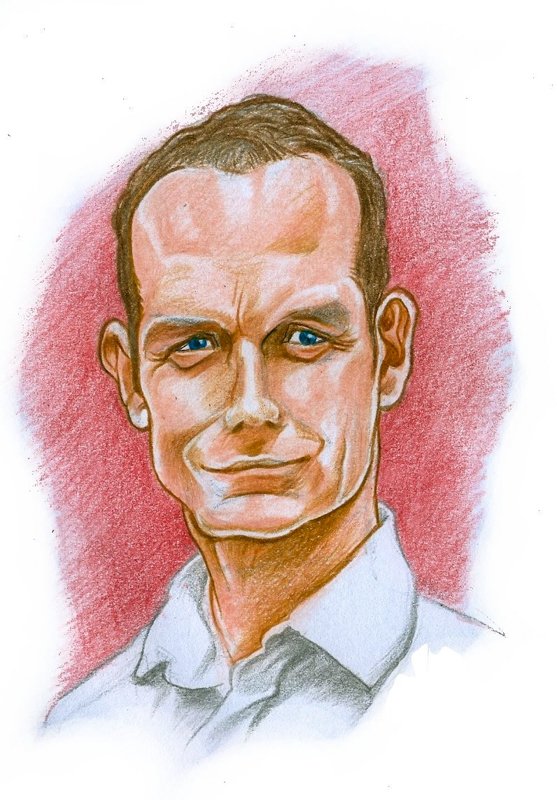

When Dr Neville Cox was approached in 2011 to take part in the Phil’s annual Liferaft debate, it was immediately clear that an ounce of acting would be required. Tasked with evoking the devil’s advocate, Cox took to the job with ease. Perched, world weary and irritated at the Phil podium, he tore through the promises of scientists to cure cancer, the admiration of Shakespeare by English lecturers, and the very existence of a drama school. Finally, he announced that Trinity lecturers were “all complete charlatans, because we’ve convinced you that without us the world wouldn’t happen”. Indeed, his performance was that of a stereotypical law professional – cynical, argumentative and fiercely unafraid – such that, should you want to, it would be enormously easy to characterise the new Dean of Graduate Studies as a Liar Liar extra.

In reality, he’s more like Atticus Finch, with a touch of Hamilton’s wit, and certainly the video of the debate shows this side of him. Enormously funny, with a subtle flair for theatrics that can’t help but leak out, and a willingness to completely devote himself to the challenge at hand, this is the Neville Cox that often greets students outside of the classroom, while the other, more detached and analytical incarnation reigns supreme inside it. When discussing the debate five years later, he shows a keen awareness of the importance of perception of his character, particularly in terms of the students it reaches, saying “God, I hope everyone knows that I’m told that I have to be the devil’s advocate”.

From this alone it is clear that Cox has many of the necessary skills required to be Dean of Graduate Studies, his new position in College. Having taken on the position earlier this month, he will be responsible for the admission, progression and examination of Trinity’s postgraduate students, as well as representing them across various College bodies. Postgraduate care is an area in which Cox has enormous prior experience, having served as the first Director of Postgraduate Teaching and Learning.

“He’s absolutely not afraid to probe any area of law or values philosophy. He’s not a guy that necessarily goes along with conventional views”

Born in Dublin and schooled at St Andrew’s College, Cox’s route to teaching was governed largely by chance. He admits that, until very shortly before coming to college, he didn’t know he was going to study law, saying “I originally wanted to do English or music, and my elder brother changed my mind”. Putting his decision down to “fun”, he summises that it was a serendipitous development, as was his entry into academia: “I don’t really know how I ended up in teaching, but sometimes the right things happen.”

Cox’s experience of college is similar to that of most freshers: enthralled by the “freedom of coming to university” and encountering a community of people with which you suddenly share the amazing privilege of studying in Trinity. Far from a society hack, Cox dabbled with debating and sport, but found an outlet for the well of fresher’s energy and enthusiasm in amateur dramatic groups around Dublin, which he now looks back on “as being an extraordinary waste of time”.

Questionable uses of time aside, it is in hearing Cox recall his first year that his capacity for compassion emerges. He says that for potentially every student, “the first term for a first year student is the most difficult they’ll have in university”, due to the change of environment, the onset of winter so soon afterwards and the sense of finality in having chosen a field with a clear career route, such as law. It has certainly informed how he treats his first-year students: “I always say to first years, just sit tight, it’ll be okay and just bear in mind that you probably will have these feelings but the person next to you is having them too.”

Despite this, Cox doesn’t go easy on his students in class, and is committed to pressing at the boundaries of their critical thinking. Teaching a range of topics, from Islamic law to Irish legal systems to medical law and ethics, enables him to grapple with both contentious issues and the fresh and ever-evolving young minds in his lecture theatre, which he calls an “incredible pleasure”. Speaking to The University Times, Fellow Emeritus and former Regius Professor of Laws in Trinity, William Binchy, attests to this: “He’s absolutely not afraid to probe any area of law or values philosophy. He’s not a guy that necessarily goes along with conventional views.”

Cox is clear on the distinct differences faced by master’s and PhD students, and is particularly sympathetic to the aspect of isolation that comes with the latter

Certainly, there is no shortage of students willing to agree with this. Recent graduate, Kevin Flood, recalls an early class with Cox: “There was a real life case of a march in a town in America that had a lot of Holocaust survivors in it, and neo-Nazis wanted to march down the main street, I think in honour of Hitler’s birthday. He said, should they be allowed march down? We obviously all said, well, no because that’s just horrible. And he said, well it’s horrible to you, but who are you to decide what’s horrible? You left the module kind of going, maybe we were wrong.” Fourth-year law student and Chair of TCD Law Soc, Hilary Hogan, agrees, adding that “he’s always quick to push [students] on the weakest part of their argument”.

When asked how he separates his own beliefs from the highly complex political and moral subjects he teaches, Cox’s response is deadpan: “I don’t really have very many beliefs on stuff.” It seems impossible, given the politically charged topics that could arise in a module like medical law, such as euthanasia and surrogacy, but he asserts that he is “so conscious” of not allowing it to come into his teaching.

What acts as the foil to this fearless and rigorous classroom ethic is a ceaseless focus on kindness. In his own words: “Knowledge and research and so on are all wonderful things, they’re my life really, but kindness is absolutely indispensable.” Binchy attests to this, saying that “while he’s got the highest of standards, he’s totally sensitive to all people in different working areas, and is tremendously caring for people who are in difficulties and challenges”. Flood notes that often times Cox can seem “quite cold to a certain extent in lectures, because he wants to be devil’s advocate and he wants to get a discussion going”, but that in person he’s extremely warm. His work as a tutor over the years, which he calls “the biggest privilege connected with being a member of academic staff in Trinity”, has tuned him to the needs of students, such that he’s become something of an unofficial welfare officer for the School of Law.

It is a sad reality that more often than not university lecturers maintain a polite disengagement from students, and particularly in matters of great personal sensitivity. It is for this reason that Cox is something of an anomaly, often going out of his way to help a struggling student. He says that his greatest influence in his career was the late Len Fromm, former Dean of Students at Indiana University, who “changed the culture of a city” with his kindness and compassion towards students. By all accounts a phenomenal academic, his legacy spanned universities, cities and colleges, as well as the various law firms he secured positions in for graduates.

Recalling a summer program that Fromm would be attending, Cox recalls: “It was slightly odd, because it was like [the students] were announcing the coming of the Messiah or something like that. These are guys that had gone through university, are now in law school, they’re tired, they’re cynical, they’re hugely in debt and they’re fundamentalist Christians, lesbian atheists and all were saying exactly the same thing about this guy.”

His wit is central to one of Trinity’s most niche events, the Law School Cabaret, at which Cox composes lyrics based on current collegiate affairs

As the Dean of Graduate Studies, Cox will have a far more focused area of attention than Fromm in addressing the interests of postgraduates. Cox is clear on the distinct differences faced by master’s and PhD students, and is particularly sympathetic to the aspect of isolation that comes with the latter: “It really is you, you’re ploughing potentially a very lonely furrow”. He praises Trinity’s introduction of structured PhDs in combating this pervasive issue, for no other reason than it brings people together.

It would be reasonable to assume that a career spent debating rights and ethics, while supporting legions of students, would leave Cox with little time for play, but nothing could be further from the truth. Speaking to The University Times, Trinity Senator and Reid Professor of Criminal Law, Ivana Bacik, notes that it’s Cox’s sense of humour that she sees as his stand out quality, adding: “He’s someone who’s quick to send a funny email, to lighten the mood in a meeting.” Indeed, his wit is central to one of Trinity’s most niche events, the Law School Cabaret, at which Cox composes lyrics based on current collegiate affairs. Far from being a passing hobby, Binchy stresses that “he could make his living out of this”, comparing him to the famed satire pianist, Tom Lehrer.

In the course of researching this profile, there were more than enough anecdotes to prove that Neville Cox is an extraordinary academic, possessed of extraordinary kindness and heart. But such stories, like all acts of genuine kindness, are confidential. Suffice it to say that a great many things wouldn’t happen without him – many students would not have continued their study, and you can guarantee that many lectures, and something like the Law School Cabaret, wouldn’t be half as interesting.