Trinity houses an impressive collection of valuable items: a vast collection of paintings that includes a Picasso, a little-known but world-class taxidermy collection, some fascinating oddities in the Museum Building, popular sculptures including Arnaldo Pomodoro’s “Sfera con Sfera” outside the Berkeley Library, and the world-famous Long Room and the items housed within it. Especially in the case of the latter, many items could warrant entire museums of their own. However, considering Trinity is a functioning university that remains short on resources, including space, we often don’t see many of these items displayed at all, meaning that the staggering historical, artistic and national political value of these items is too-often not conveyed.

The tours that are given in the college focus mainly on what tourists want: facts about Trinity itself and its architecture. Aside from the odd exhibition in the middle of the room, trips to the Long Room focus almost exclusively on the artistic value of the Book of Kells and the beauty of the room itself, when there is so much more to it. Only two pages of the Book of Kells are visible at a time in a dimly lit room when over six hundred pages have been digitised, some with details only visible when magnified to poster size.

The staggering historical, artistic and national political value of these items is too-often not conveyed

Visitors to the book learn little about the importance of Ireland’s monastic scribing traditions. Furthermore, they learn nothing about the Viking invasion which shaped the country and moved the Book to Kells, nor indeed about the invasion by Cromwell that moved it to Trinity. The College also possesses the Book of Armagh, a testament to Old Irish written for St Patrick’s heir which is arguably of greater historical importance than the Book of Kells itself.

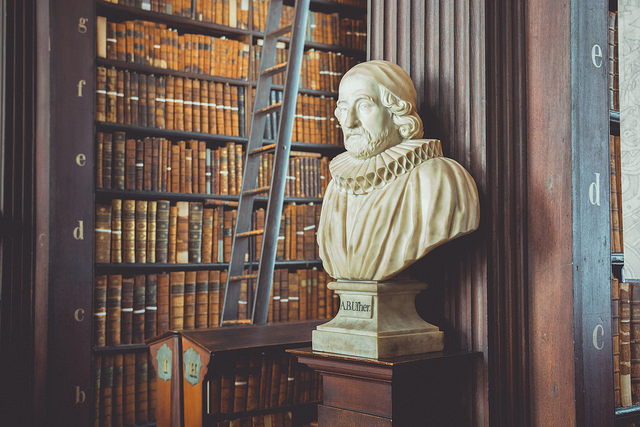

Going up the stairs from the Book of Kells, an original copy of the Proclamation is on display. It is one of only 30 or so originals left in existence but, in a year in which every child in the country learned about the Proclamation, nowhere near enough has been done to use it for the commemoration or to draw attention to it. The audio guide also draws attention to the fact that the library may have inspired a set in Star Wars while failing to mention that the visitor is walking past a unique collection of busts or how the library came to be from a few private collections.

The inaccessibility of much of the library’s content is also worth noting. There are a huge number of books that are either hidden away in Stacks or unreachable in the Long Room itself. For example, the Long Room houses over 200,000 of the library’s oldest books. However, a large proportion of these are inaccessible as they are on shelves which are out of reach for most.

Finally, sitting innocuously to one side, is a large harp. The plaque is small and gives little information. Only the few who have paid for the audio guide will be told that it was long associated with Brian Boru (despite never having actually belonged to him) and is one of only three medieval Gaelic harps remaining today. Only the exceptionally curious will later look it up and realise they were standing in front of the symbol of Ireland, found on Irish passports and seals.

The loss involved isn’t simply historical but political too. Nations rely on symbols and shared history: failing to use the harp as a jumping point to talk about Brian Boru and an example of a nation that dates back over a millennium is a shocking oversight. Worse, if tourists don’t understand why what they are looking at is important, they are unlikely to feel their money well spent. Nonetheless, according to the library’s website, “hundreds of thousands of visitors visit the Old Library every year”, so it is hard to tell how much, if anything, is being lost in monetary terms.

Trinity is leading the way in digitising its collections and modernising how a university can run, but too often the unique, physical objects it holds aren’t shared in the way they should.

Trinity is leading the way in digitising its collections and modernising how a university can run, but too often the unique, physical objects it holds aren’t shared in the way they should.

It is difficult to see what can be done about it, however. As noted previously, Trinity is a university and, as the library website puts it: “The academic work of the University, its teaching, learning and research take precedence over tourism”. If it can’t do justice to these valuable objects, it is because of a lack of resources and – most critically – a lack of space. The Long Room has made excellent temporary exhibitions which include one on Brian Boru and one on the Easter Rising, but they take up too much space to allow any to be large or permanent, and many tourists are unlikely to give them more than a glance.

When Trinity is unable to do justice to its collection, we have to ask what it has done to deserve it. Wouldn’t the state and Irish heritage get a greater benefit by placing it in the national history museum or even in Kells or Newgrange, as some people are campaigning for? I asked one of the tour guides their opinion on the idea of moving the collection but they were dubious and rightly so: “People come for the Book of Kells but they stay for the Long Library.” Taking the Book of Kells away from Trinity would likely prevent it from monetising its footfall or from even having a footfall at all. Worse, if it was handled badly, the collection could end up in an out of the way museum that nobody visits, aggravating the waste and costing a fortune.

Above all, we can’t simply continue to remain in a worst-of-both-worlds situation. We can choose to prioritise education over heritage and sell our collection to the state (which would hopefully put it to better use) or give up some of the space presently used for teaching towards a proper museum. Neither of those options would be popular, as Trinity neither wants to give up its treasures and the revenue they generate, nor sacrifice much-needed space elsewhere and give them, and the tourists, the space they need.