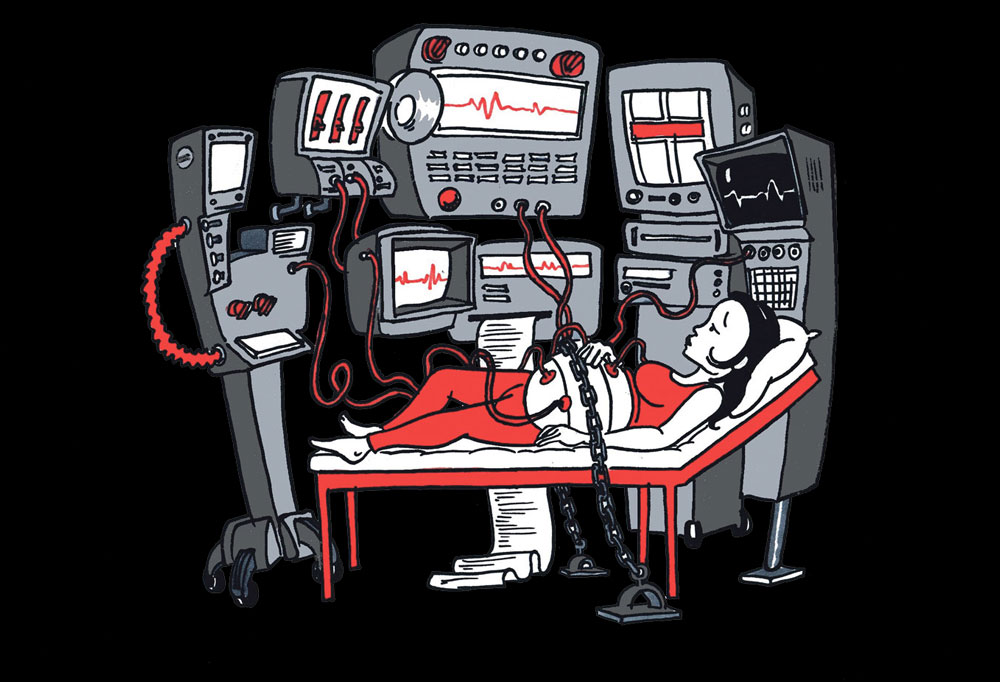

In Martha C Nussbaum’s book Sex and Social Justice, she outlines the seven ways one can treat another human being as a thing. It can range, among other methods, from using them for one’s own gain (instrumentality), dismissing their lived experiences (denial of subjectivity), treating them as something to be broken into (violability) or simply denying them a voice. The latter, “inertness”, is arguably the most insidious, so gradual and subtle a process that not only can one quickly lose a voice – one can feel they’ve no right to a voice in the first place. So far, the movement to repeal the eighth amendment has centered on these violations: the denial of choice, of autonomy, of safety, the dismissal of experience and the threat of violence towards the female body.

While already hugely successful, the campaign runs the risk of appearing as a young woman’s movement, and while considerable attention is paid to the veteran activists who have been fighting this fight for 30 years, little is paid to those in the middle: the mothers who want to continue their pregnancies out of the shadow of the eighth. It will not have occurred to a large part of the electorate that there are considerable implications of the amendment on “happily pregnant women”, in terms of medical procedures either forced or withheld, but they are just as dehumanised as the rest of the female population. With 69,000 recorded pregnancies in Ireland – not counting those of women who go through England for abortions – mothers, women who want children and even those who haven’t made up their minds are negatively affected by the eighth amendment just as those in crisis pregnancies are. Worse still, they are largely forgotten.

Much of this has to do with societal expectations. Consider the first time you came into contact with the subject of abortion: who has them, why, when and where? For me, as with many of my formative – often deeply flawed – introductions to the complexities of young womanhood, my first understanding of these questions came from the most problematic of faves: Carrie Bradshaw. In an iconic early-2000s episode entitled “Coulda Woulda Shoulda”, the women of Sex and the City grapple with the question of abortion with about as nuance as a 30-minute episode will permit. Hard-boiled lawyer type, Miranda Hobbes, finds herself unexpectedly pregnant, while WASP extraordinaire, Charlotte York, struggles with envy and a buried fertility issue and Samantha Jones, a hangover from the 1980s business woman trope, yearns for a baby of her own: an Hermès Birkin.

Bradshaw, on the other hand, recalls her own crisis pregnancy, a plot point that 15 years later still promotes a stereotypical idea of what kind of women seek abortions. At 22, Bradshaw was an ambitious ingenue, barely able to support herself in the cutthroat New York society, let alone a child, by all appearances devoted to a way of life that favoured her and her alone and suddenly pregnant. She glosses over the process of termination, but her anguish and brief fling with regret highlights the social expectation of what viewers think a woman who has had an abortion feels, looks and grieves. Though by the end of the episode, our Chanel-draped champion has reaffirmed her own belief in abortion being the right choice for her, there’s still those 20 minutes of soul-searching that feel too much like peddling to the masses.

With 69,000 recorded pregnancies in Ireland – not counting those of women who go through England for abortions – mothers, women who want children and even those who haven’t made up their minds are negatively affected by the eighth amendment just as those in crisis pregnancies are.

Therein lies the trouble with representing abortions and the women who get them in the media: there is no catch-all version of it and in the attempt to distinguish one for the sake of a campaign either for or against repealing the eighth, very easily a pattern can emerge. The reality is that there is no pattern. Of all women getting abortions, 70 per cent are mothers already and, as numerous studies have shown, draconian abortion laws have the opposite effect on women seeking abortions as hoped for, particularly in the case of women with children as funds are even more constrained. The implications of the eighth amendment on women happy to continue pregnancies are complex and manifold, but there are legitimate concerns that their demographic are not being accurately represented.

On an early September afternoon, scintillant after one of the first rainfalls of the season, I meet Rebecca Flynn and Aoife Dermody of activism group Parents for Choice in a charming but almost empty cafe off of O’Connell St. I go in with few expectations, knowing that there’s nothing to signal to me that the two women, both in their mid-thirties, are here to discuss reproductive rights and freedom of choice, so when I spot Flynn in her Repeal t-shirt I breathe a sigh of relief. It’s getting late and my three coffees are wearing off, robbing me of the energy to search a room for my interviewees. Our initial chatter is easy and informal: we discuss how perfect the cafe would be as a wedding venue, possessed as it is of nooks and crannies and blank enough to allow for inventive design. Dermody buys me coffee, and after that alone I am at ease. These aren’t hashtagging 20-something year olds, relatively new inheritors of a long standing social and political burden, but mammies. They’re stressed and wise and really funny. Make no mistake, they are furious, and sick and tired of the state of affairs, but more on that later.

Parents for Choice began informally as a Facebook group for mothers to discuss the political and social upheaval following the death of Savita Halappanar due to complications during pregnancy in 2012 and the Ms Y case of 2014, where a migrant woman, raped in her home country, unsuccessfully sought an abortion in Ireland. Both women, however, have long associations with feminist activism: Dermody has been an activist for many years, having gotten involved in pro-choice activism in the last eight years, while Flynn mentions that her mother worked for the Well Woman Centre when she was young, and that she attended her first march as an 11 year-old in light of the X case, chanting “spuck off” alongside other bastions of female anger and resilience. The Ms Y case coincided with the birth of Flynn’s son, and she recalls marching with women from the group, her young son still in a baby carrier. It was after that, she says, that discussion among the group turned to mobilising members and “becoming an actual organisation”.

Even more central to this, however, is their assertion that choosing to continue a pregnancy in Ireland is just as treacherous an experience as choosing to terminate one.

Dermody is keen to stress the purpose behind setting up yet another campaign group among the many that already exist: “Previously where we could go to a meeting at half eight, now we’re desperately trying to get small people to sleep or wash the avocado off their clothes or whatever. So for us finding a space where we could primarily organise online [was the focus], because not a lot of groups favour that – they prefer the dynamism of groups and planning in person, which is totally legitimate. But for us we needed to create a space for ourselves where we could organise online, where we could be free to dip in and out as we needed to.” Their activism, therefore, is largely in the vein of sending letters, press releases, social media and blogging – modes of communication that perfectly suit their target audience. Even more central to this, however, is their assertion that choosing to continue a pregnancy in Ireland is just as treacherous an experience as choosing to terminate one. As Dermody says: “We have experienced having to choose whether to remain pregnant or not, we’ve had to experience going through pregnancy and childbirth and having a number of choices denied to us, denial of consent, lack of information.” For this reason, Parents for Choice are vehemently pro-choice: “There’s a huge culture of paternalism in the whole system where women are, in law and then in practice, treated like children or an adult without the mental capacity to make a decision for themselves.”

What Dermody is referring to are the deeply flawed maternity services in Ireland, a system far below the international standard for care and, due to its devaluing of women and their opinions and experiences, the source of many traumatic experiences. It’s a topic that Liz Kelly, the Woman’s Support rep for Association for Improvements in Maternity Services (AIMS) Ireland, speaks of with reticent conviction, having led a career offering support and validation for hundreds of women still traumatised by their birth experiences. Established in 2007, and run on a voluntary basis, AIMS calls for evidence-based care and full autonomy for women, both of which are absent from standard practice of care. She recalls: “I started to see women coming to me after a first pregnancy, about seven months pregnant, when it would be sort of imminent, and they were really really scared and very very nervous, simply of the upcoming birth, simply because of experience they’d had. They felt out of control.” An assortment of invasive, unwarranted procedures, both forced and denied, contribute to this sense of powerlessness, with scarcely issued anomaly scans – used to show the anatomy of the baby, as well as abnormalities – prohibiting an opportunity for the woman to prepare while membrane sweeps – “exactly what it sounds like” – are one of many painful practices often carried out without a woman’s permission or knowledge. If this is the prospect awaiting expectant mothers in Ireland, how can you state, as your strongest argument against abortion, that it’s a country that values motherhood?

Other practices are less logical still. Kelly has particular issues with due dates, which she sees as the first mistreatment of pregnant women in the system. Explaining that international best practice – a phrase one becomes increasingly familiar with the longer this information is pored over – recognises that length of pregnancy can vary from 37 to 42 weeks, she states that Ireland refuses to budge from the completely arbitrary and outdated length of 40 weeks. The knock-on effect of this is a fixed due date that neglects to take a woman’s family history into account. Once the pregnancy deviates from the “norm”, artificial induction is introduced, either with a membrane sweep or with the chemical syntocinon. The grand irony with the latter is that it completely disrupts the natural chemical progression of a pregnancy, leading to both the mother and baby becoming distressed and a higher risk labour. I’m immediately reminded of the recent comments by Patrick Jameson, director of The Women’s Centre in Dublin, who claimed that the chemical disruption caused by abortion triggered the onset of breast cancer. But perhaps the most absurd expectation placed on the pregnant female body is that, under the Active Management of Labour introduced in 1968 by the National Maternity Hospital, Holles Street, a woman must dilate 1cm per hour, unless she be artificially induced. At one point in our interview Flynn refers to Ireland’s treatment of women, both happily and unhappily pregnant, as “dystopian” and certainly the latter detail wouldn’t go amiss in Brave New World.

These instances of dismissal, disrespect, control and violence against pregnant women are precisely why Flynn says she “realised, from being in particular spaces on Facebook with regards to maternity care, that right now, while I’m pregnant I am in danger”. Her own labour was far from the comfort and ease of Beyoncé’s post-birth glamour shots, as the vast majority of births are: physically confined to the hospital bed, she was fixed with a CTG monitor – a notoriously faulty method of monitoring a baby that, due to its inaccuracy, often leads to a gamut of interventions such as C-sections – against her wishes. Over her coffee, she recalls fighting the doctors on the matter, issuing the staff with a highly researched spiel on international best practice in between “cow moos”. She laughs, despite the systematic denial of agency or consent so commonplace in our maternity services, because, really, what more can you do after the fact?

“After the fact” is indeed the dark void new mothers are left to grapple with once discharged from maternity care. It’s also the period when doubt, guilt and overwhelming shame can set in – sound familiar?

By privileging the life of the foetus above that of the mother, the eighth amendment subtly tells a woman that she is little more than a vessel, with specific expectations placed upon her. In this sense, the women happy to continue a pregnancy are further aligned with those who are not. As Flynn notes, there is a dialogue of permission and restriction once you enter the system as pregnant – “Are you allowed to do this, or that?” – that subtly affirms a woman’s lack of agency. Should a woman deviate from these restrictions and expectations, she can be exposed to intense pressure. While Dermody acknowledges that many women find their care acceptable, she also asserts that “what we know is that people have, in extreme cases, been threatened with the eighth. Doctors will threaten to bring a woman to court if she doesn’t undergo a particular procedure. We know that’s documented”.

All these kind of threats, basically threats, that the woman would be to blame if anything happens to the baby. And I mean that’s enough to make any woman comply with whatever is being forced on her.

It is this area that Kelly has the most experience. She explains that in the months and even years after the birth of their child, women grapple with the sense that their treatment during labour was deeply flawed. Even more interesting is, in comparison to this unease, that 92 per cent of women who had abortions said that they felt confident it was the right choice for them. Kelly is particularly attuned to the feelings of women who went into the maternity services with trust only to leave dissatisfied. “They’re living with it and feeling guilty about speaking about it and feeling like their baby is okay, and they were okay, so what they can change about it?” Aside from the potential physical wounds after birth, it is the psychological harm that lingers the longest. When asked what comments she’s heard from women during their care, her reply is yet again quiet but outraged: “Mostly, it would be ‘Do you want your baby to die?’ That is constantly used, you hear that constantly. There are other things like, ‘Oh, it would be your fault if something like this happens”. All these kind of threats, basically threats, that the woman would be to blame if anything happens to the baby. And I mean that’s enough to make any woman comply with whatever is being forced on her.” And while this is in no way across the board, Kelly is adamant that reform is needed for the sake of those who are affected, particularly when harmful interventions are arising from normal occurrences. As she says: “You don’t have the fire brigade anytime you put on a slice of toast.”

The perception of mothers being anti-repeal is a pervasive one, and yet again comes from societal preconception and denial of an individual’s right to choice. As Dermody says: “People are genuinely surprised that people who have been pregnant and have a child could be pro-choice, people who might not have thought about it too deeply. They think that the only reason people are pro-choice is because they hate children or something.” But both she and Flynn argue that their community of parents are more like students than is immediately apparent: “The unique thing about us is we’re broke, like students. We’re fucking broke because we’ve got little kids, man. It’s a big change in circumstances.”

Indeed, this is something that historian Mary Muldowney seconds. When I asked what prompted her consideration of her reproductive rights, in a calm, measured and melodic voice she replies: “When I had a crisis pregnancy when I was 17.” Happy to continue the pregnancy but forced to move to London to avoid a forced adoption, Muldowney – who studies the history of the eighth amendment – recalls how persistent the stereotype of young, unmarried Irish women being the ones to seek abortions was: “I went to the hospital for the first antenatal session and it was assumed that because I was Irish and young I must want a termination.” Indeed, as she states, “England was always a great escape hole for Irish social problems.” By the time of the 1983 referendum, Muldowney had two children but was adamant that future generations should not be forced to live under such draconian limitations. In an image sweetly similar to that of Flynn marching with her newborn, Muldowney took to the streets, a buggy in one hand, a stack of pro-choice leaflets in the other. Certainly there can be no set model for a pro-choice woman, and the parents in favour of repealing the eighth are anything but stereotypical.

The unique thing about us is we’re broke, like students. We’re fucking broke because we’ve got little kids, man. It’s a big change in circumstances.

When speaking with organisations involved in the campaign to repeal the eighth, one of the predominant feelings, after sheer rage, is trepidation. Those working to open access to free, safe, legal abortion are, due to their understanding of the law and its implementation in society, fully aware of the gaps that will remain once the amendment is stricken from the Constitution. One such gap is in maternity services, and this is what both Parents for Choice and AIMS are truly working towards. Kelly mentions that part of AIMS’s advocacy is going directly to the hospitals and give them feedback based on their experience because “consent is a human rights issue, bodily autonomy and consent is a human rights issue. So without the eighth amendment we would still have to fight that battle, there would still be battles for consent, for information, for informed choice and informed consent.” Parents for Choice second this, as Flynn says “the eighth, if and when it gets repealed” – Aoife cuts in to correct her, “when” – “we know that we’ll still have a lot of work to do”.

If the population of Ireland’s women who seek abortion are a community cast out to sea, then the mothers and expectant mothers are those with their roots buried in Ireland’s fertile earth. Balancing a campaign to repeal the eighth amendment with a young family is no easy task. Over the course of our brief interview, both Flynn and Dermody lose their trains of thought, pause with tiredness and eventually hurry off back to work and their families. “Pregnancy is not mad craic. It’s fucking hard work”, Dermody says, deadpan but somehow still brimming with affection. “So when people are like, you should take the decision to have an abortion very seriously, I’m like, ‘you should take the decision to remain pregnant very seriously because it’s fundamentally and utterly life changing on your body, on your relationships, on your mental health.’” Still, they find time to bond over that which could otherwise divide them, holding group meetings in crowded houses, over tea and cake, and with young children running around their ankles. I’m as big a fan of the jumpers and poems and videos as anyone else, but more of this narrative please. It’s one of the most joyous images this campaign has produced, amid an already successful output.