House Six has always been at the centre of student life in Trinity. Despite plans for a new student centre in the near future, House Six always will be the place of memories, from the dear to the dramatic, for those who have climbed its stairs and passed through its door. Talking to several previous Trinity College Dublin Students’ Union (TCDSU) officers and Trinity alumni, one gets the sense of the countless great things that have happened within its crumbling, often claustrophobic, walls.

As former TCDSU Education Officer from 2013/14 Jack Leahy puts it, speaking to The University Times: “You like it for what it is because it’s your thing, not because it is the best thing.”

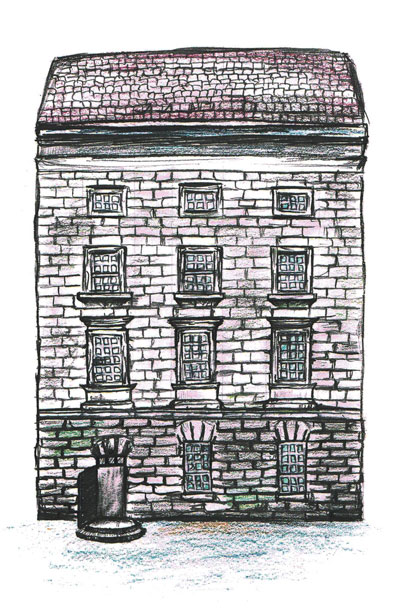

Joseph O’Gorman, the Strategic Director of the Central Societies Committee (CSC), Assistant Junior Dean and Trinity alumnus, boasts that his cosy office was the original office of the CSC in House Six in 1969. He talks passionately about the importance of House Six as the “heartbeat” of the student community in Trinity, adding that it has always housed students in some way or another. Currently TCDSU, several societies, a shop and the CSC all call the palladian-style building home. Originally, it was a home of sorts, acting as a “self-contained unit” for tutors and their students to live and study in, back in the mid to late 1700s.

Since the gifting of House Six to the students’ union, its dilapidated glory has been the centre of campus life. Joe Duffy, TCDSU President for 1979/80 and RTÉ radio presenter, when speaking to The University Times, described the gift as “very generous of them [the College]”.

The building has played a central role in shaping Trinity, but will also go down in history as the backdrop to one of the greatest controversies of modern Ireland. In 1989, then-TCDSU President and current University of Dublin Senator, Ivana Bacik, struck a blow for abortion rights when she published and promoted information on abortion, which was illegal at the time. Inside its “shabby warren of rooms”, the first condom machine in Ireland was installed, while campaigning against the criminalisation of homosexuality also occurred within these walls.

Trinity, in all their stupidity, decided that the only thing they could do to get us out of the JCR was not to negotiate with us but to actually go to the High Court and get an injunction.

The building itself could tell endless stories of rebellious students causing havoc, whether it be to “annoy College” as Duffy says or to evoke change in Irish law. The building is “based on a design by a Danish architect, Theodore Jacobson”, O’Gorman explains, adding the fact that Jacobson was not paid for his endeavour.

Now though, after years of use, the building isn’t “fit for purpose”, says Leahy. O’Gorman, however, argues that this is what fosters a sense of community within the building, that we are all making do with what we have got. The University Times’s office is certainly not big enough for its mission, but like every other society or group that calls this building home, we make do.

Leahy makes testament to this: “This building will always be for me…the building that didn’t give people the opportunity to do as well as they did. Like, there is no way societies and publications, to the standard that they are, should have been produced from these facilities.”

O’Gorman agrees. “It’s shabby, it’s not perfect…it’s not precisely fit for purpose, but it is fitted to the purpose, because people make do with what they have, it’s better that way, if everything is just squeaky clean then what’s the point?”

Speaking to The University Times about his time in the students’ union in House Six, Duffy describes a more rebellious time for TCDSU when every little inconvenience and injustice was reason enough to occupy the JCR – now known as Regent House – or some other building on campus.

One instance in particular involved High Court injunctions and notes slipped through the fire escape in the fireplace – “extraordinary for a fire exit”, O’Gorman comments – between students in the JCR and House Six. Students would “pontificate” within the room and “write out a letter and send it back with demands to the College Board”, O’Gorman explains.

“Trinity, in all their stupidity, decided that the only thing they could do to get us out of the JCR was not to negotiate with us but to actually go to the High Court and get an injunction”, Duffy says. “Front Gate opened fully and two paddy wagons came in from Pearse St Garda Station and arrested us and brought us to the High Court.” The College then had to get a second injunction to lift the charges. The moment the students were let go, they “promptly went back into the JCR”.

One would be forgiven for thinking that something extremely serious caused such a strong reaction from both the students and College. Yet Duffy explains that the occupation was due to increased prices in the Buttery, and issues around the “subsidisation of Commons”.

“Those were the campaigns at the time, condoms, fees, library space and prices in college”, Duffy recalls.

It was in Duffy’s year when the condom machine was first installed: “That is a great location, you have everyone coming through Front Gate and they pop into the shop, and that was a serious source of income for the students’ union.”

A more serious arrest within the bricks of the building was of Bacik and her fellow union officers back in 1989: “We had papers served on us that said we were likely to go to jail if we continued to distribute the student handbook because it contained information on abortion, so we were chased through those offices by police.”

The papers said that they had “conspired to corrupt the public moral”. The story is a familiar one – Mary Robinson represented them in court and charges were eventually dropped. But it captures the sheer range of events the residents of House Six have witnessed.

Number six must be the best-located students’ union office in these islands, because it is so strategic, so central.

Bacik also recalls a more “Trinity issue”, involving a “long-running issue about the fact the union shop sold tuna and issues around animal welfare and how the tuna is caught”. It became so big for the union it ended up forming policy for the union, and Bacik was caught in between the students fighting for animal rights and the shop manager at the time.

A stand-out memory for Leahy is of the consistent plotting and politics that rumbled on in the house, which nearly led to the impeachment of Tom Lenihan as President of TCDSU in Leahy’s year as Education Officer.

It would be strange to write a piece about House Six and not acknowledge its location in Dublin, as Duffy describes it: “Number six must be the best-located students’ union office in these islands, because it is so strategic, so central.”

He’s not wrong. Just looking out onto College Green and up Dame St, you watch the world go by, and you can imagine the incredible moments House Six has been central to. Front Square and House Six are the meeting places for every major march in the capital, as was demonstrated by the March for Choice on September 30th and the March for Education just last Wednesday.

Yet we should also acknowledge the view House Six has over Front Square. Vice-Provost Chris Morash reflects on his summer as President of the Graduate Students’ Union (GSU). Morash fondly remembers looking out on Front Square from the window of his office and counting the tourists taking photos of the campanile: “The thing that really struck me most was the first time you have that comprehensive view of Front Square…as a student, you really get a sense of the life of the place.”

House Six doesn’t just owe its 270-year history to union officers, but also to those who have quietly worked away for the union and its offices over the years. One such woman, who sadly passed away just three weeks ago at the age of 90, was Clare Kelly, who began working for the Public Office of TCDSU as an office manager in the mid-1960s until her retirement in 1992. Bacik explains that she was a “mother figure to everyone, and smoked like a trooper”, but she “loved being surrounded by students” and truly was “the face of House Six”, quietly helping students and supporting the union’s campaigns.

Long before the 1960s, House Six was an important and central hub for women in College. The Eliz Room on the first floor was home to the Elizabethan Society, a debating society established for women until their amalgamation into the Philosophical Society (the Phil) in the 1970s, as women were not allowed to be members of the Phil or the College Historical Society (the Hist). So important was the building, and particularly the Eliz Room, to women, that the Marquess of Ormonde donated money to College to provide accommodation to women in House Six and to renovate the Eliz Room in 1965.

For anyone who has ever stumbled across its steps and dared to look inside its grand exterior, including those I spoke to and certainly myself, House Six has, and always will, hold extremely fond memories.

When the student centre is built, superseding House Six, O’Gorman will not be following the union’s’ sabbatical officers out of the building: “The only way you will get me to leave this building involves a wooden box.”