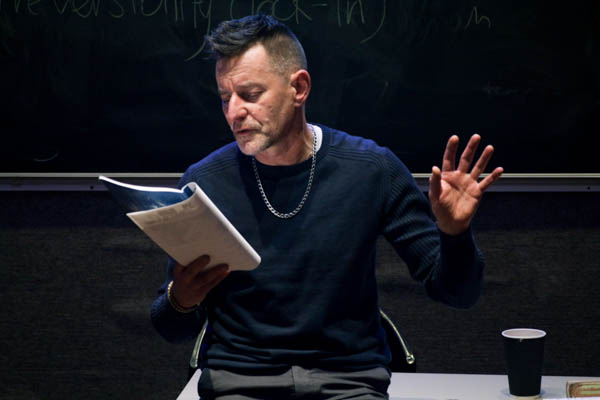

Tonie Walsh’s three-tone jacket and bright orange trainers made him blend right into the throng of students congesting the Arts Block. He bustled into Swift Theatre and strode down the steps of the intimate hall, brushing by with an infectious air of excitement. Having overheard murmurs of delight on the scattered audience over his earlier talk “Queer Treasure”, I couldn’t help but be intrigued to hear the life of the man who helped to salvage and preserve the history of the struggles of the LGBT community in Ireland. After an abrupt disappearance to the bathroom, he quickly leapt back in and launched into the script of his play, I am Tonie Walsh.

His play, Walsh explained, “is as much a script as it is a memoir”. Having kept journals all through his adolescence and into his adult life, Walsh inadvertently produced a collection of, in effect, invaluable history books. Recording life experiences of first loves, lost friends, family struggles, not to mention his pioneering work as an LGBT activist, Walsh’s play narrates a wide range of personal and social reminiscences. The play, as Walsh puts it himself “is a simple meditation of family, friends and community”, and is one in which everyone can find an experience to identify with.

Born in 1960, Walsh’s life has spanned through six decades of tumultuous, turbulent Irish social history. From the ignored murders of gay men in the 1970s, the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and all the way to the same-sex marriage referendum in 2015, Walsh has well and truly been witness to, and an advocate for, a fundamental shift in societal and cultural outlooks over the last 50 years. As he shifted from one decade to another, he moved nervously around the platform. He read his script awkwardly at first, unnerved, he later explained, at the realisation that an audience is finally hearing his story.

As he progressed through the 13 scenes, Walsh recounted his memories in exquisite detail as he settled into a deep reverie of days gone past. With the laughs that came with his sharp-witted, personality-exuberant “memoir”, came the accompanying tears that Walsh struggles to hold in. He apologetically coughed them off as he recounted the loss of yet another AIDS victim, before quickly jumping ahead to the next scene. Indeed, Walsh’s play is filled with these experiences of loss and despair, but effortlessly includes a comedic flare as his personality breaks through the narrative.

Walsh sifted through the many important milestones of his lifetime: as historic as the decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1993 and as striking as his AIDS diagnosis in 2004. These, among other stories, culminate to produce a breath-taking ending wherein Walsh’s joy at the result of the same-sex marriage referendum is undercut with feelings of deep grief as he is forced to come to terms with the recent loss of his mother.

Listening to excerpts from his 1993 journal, one could only feel lucky to be privy to such a personal account of those captured “lingering sniffs”, as Walsh labelled them, of life’s troubles and triumphs. Through Walsh’s archival collection of diaries he has managed to produce a script replete with laughs, tears and some graphic stories: a script that I look forward to seeing come to life on stage next spring.