Colour is Life is a retrospective of the prolific painter and printmaker Emil Nolde, which opened this week at the National Gallery of Ireland.

No colour, even alone, is wholly abstract. Instead, each is hued and capable of stirring a particular emotion. This phenomenal quality of colour was elaborated upon by Goethe in his Theory of Colour, most famously with the Rose of Temperaments diagram, constructed along with Schiller, which categorizes each colour on a spectrum of emotions. The colour of something is immediate and we recognise colour before anything else. Before even putting a name to something and being able to fully comprehend what it is, its colour, its emotional impact, will have touched us first. And thus is it with this exhibition, with even the most chaotic canvas, when immediately emotions strike us even before the subject is discernible.

There is no doubt that such philosophical theories brought revolutionary changes to the artworld that would never be reversed. Soon after Goethe’s conception, the power inherent in pure colour was recognised in particular by the Expressionists, first in Germany at the very cusp of World War I. These avant-gardists chose not to depict an objective vision of life, but rather a lived impression. Most famous among their circles were the likes of Egon Schiele and Edvard Munch. But a lesser-known artist stood apart, one who would also embrace colour totally and did so not only to reveal his own emotional states, but to depict the rich variety of moods the world over. This keen observer of how the different corners of the globe look to the soul was Emil Nolde. His work is an attempt to document en masse the complexity and intensity of the human experience, in all its different hues.

Among the most striking of the paintings is the scene of the “Candle Dancers”. Contained within a deep dark set frame these cropped figures seem huge, their erotic frenzy and maddening momentum pushing beyond the canvas. This painting is a striking example of Nolde’s intense use of colour to depict a palpable sense of passion and overwhelming emotion, as well as his engagement with life, for Nolde had a great love of dance and its power. But the surrealism of the scene derives from the artist’s boundless enthusiasm for life.

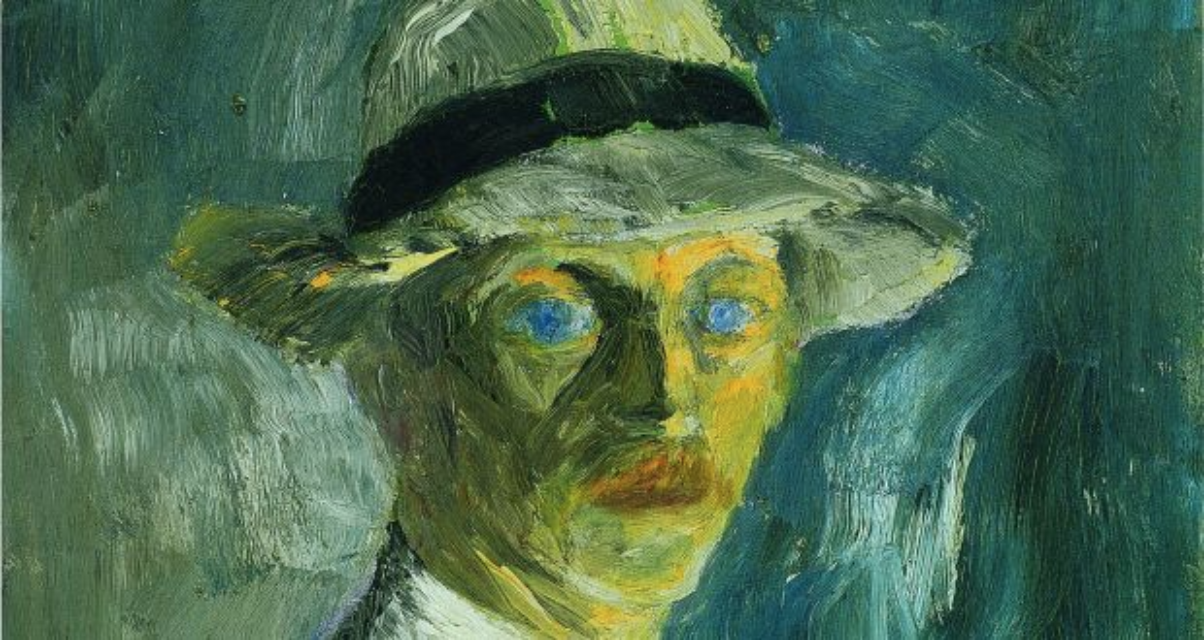

Born in 1867 in Denmark, Nolde came from a rural, Protestant background. And while he soon came to realise how unsuited he was to farm life, leaving to become an illustrator, a love for the idyllic countryside and spirituality would stick with him all his life. The farmer image is central to his early work that focuses on the energy and character of crowded markets and gatherings. A paired portrait of his parents bears no real resemblance but instead accentuates their social standing to the point of almost caricature. Accuracy of form and colour are sacrificed for a force of character. Yet it becomes clear that Nolde is aware of his actions. A still life of some masks is a haunting testament to the notion of identity in all its lurid appearances. Likewise, a self portrait shows that the most important thing to the artist is not the reality of how things look but the colour that overwhelms and pierces the blue eyes.

After 1904, Nolde spent a great deal of time in Germany, favouring Berlin in winter. He became loosely affiliated with, and inspired by, the Die Brücke group and socialised in theatres and salons.

He soon began to paint the decadent lifestyle of these metropolitans and, as was common practice for the Expressionists, his portrayal was often a sordid affair: modernity as a commotion of social entertainers, sexual tension and near violent vibrant city light. These figures look demented with their yellow faces enlarged in tightly packed rooms that burst with ceaseless energy and unnatural colours. Only the most isolated individuals or couples seem decent in smaller, more delicate watercolour sketches.

But even they seem tired, alone and desiring something more. Though counter-intuitively, Nolde seems to be an artist who avoids political commentary.

His paintings seem to reach for the honest emotions of a scene and do not aim to criticise. There are a few images that hint at the military build up and tensions in Germany, but again the visceral thrill of a crowd is always in focus, rather than the broader significance.

In 1909, after suffering a serious illness, Nolde experienced an even deeper sense of spirituality and began to paint a number of religious paintings. These, in fact, were not popular until after World War I, but then became hailed as amongst the best of Expressionism and he returned again to the subject.

Travel played a crucial role in his life and artistic practice. Amongst his most touching works are those from the Hamburg port where he stayed for five weeks, producing an incredible quantity of works. One painting on show depicts an almost unintelligible spray of colours through which a boat at sea is just about recognised. But the excitement and rapture of the artist is paramount, and Nolde described this time as one of the happiest in his life. Still inexhaustible, Nolde would continue to travel and document people in Africa, Europe, Siberia and even Asia. His sketches of tribes shows an affinity with Gauguin, whom he deeply admired.

The appeal is of course clear: these simpler ways seem so much more connected to the immediate and visceral emotions and life. On these grounds, Nolde held poor views of the colonial powers, whom he saw as robbing these tribes of their authenticity.

The work Nolde produced while traveling is among some of the most stirring. The lonesome watercolour portraits of African men are simple, yet hauntingly melancholy and are deeply moving, holding so much more humanity than their counterparts in Berlin. Appreciation of such simplicity is central to Nolde’s oeuvre, for he believed this allowed for the emotions of life to come to the fore. As he put it: “The artist need not know very much; best of all let him work instinctively and paint as naturally as he breathes or walks.”

By the end of his career, Nolde was deemed a degenerate by the Nazi regime and though a supporter of the Nationalist Socialist party he was banned from exhibiting and producing more paintings. While desperately trying to salvage what he could of his life’s work, Nolde also created a vast collection of what came to be called the Unpainted Paintings. These watercolour drawings are sketches for what might have been larger works and return to themes of identity, folklore and community in a manner that is first of all dreamlike and, of course, colourful.

Colour is Life runs until June 10th. Student admission is €5.