From Rembrandt’s emotionally wrought self-critiques evoking the anxiety of his declining career, to Frida Kahlo’s post-divorce work, representations of the self within art are complex. Self-portraits have long proved to be a consistent fixation for both spectator and artist, likely because they are human and relatable rather than buried deep in the artistic language of intellectual abstraction.

Taking a picture of ourselves is not a new concept. It is perhaps prudent to speculate that our definition of what designates a self-portrait is constantly evolving. With the meteoric rise of selfies as our leading form of visual communication, we are inundated with self-imagery. Last year the Saatchi Art Gallery held an exhibition which included self-portraits of Egon Schiele, Francis Bacon, Tracey Emin and Kim Kardashian. The exhibition was titled From Selfie to Self-Expression. Subversive showcases such as this retract the seemingly intimidating nature of visual art. It brings contemporary art to a wider audience. There is certainly a brazen intensity inherent to selfies and we are living in a confessional age where the scrutiny of artists and the masses towards themselves is apparent more than ever. Yet it is very empowering to take control in image.

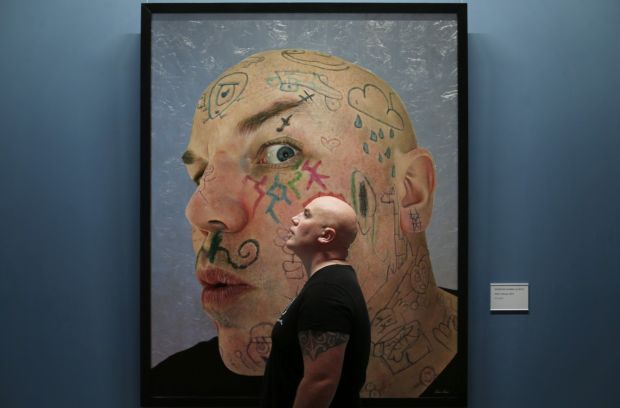

It is this that makes the upcoming Zurich Portrait Prize (formerly known as the Hennessy Portrait Prize) all the more enticing. Beginning in 2014, it is a competition for amateur artists whereby the winner’s work will be included in the National Portrait Collection amongst many other illustrious Irish names and figures. The shortlisted pieces will be on display in the National Gallery from October 6th to January 13th. There is great variation between the works chosen, and the 2016 collection notably included a portrait by James Kearney of a man in a bath, created using the sole medium of Microsoft Paint.

Speaking to The University Times, Choy-Ping Clarke-Ng, a Trinity student and artist, talked about why they were attracted to self-portraiture having never seen themselves in media or art. “If I don’t see myself then I should make an image of myself.” As both subject and artist, they are conscious of the image they want to portray. “There’s always very personal reasons as to why people make self-images as to what they are representing and why”.

The popularity of the Google Arts and Culture app scans through a database of over 6,000 exhibitions to find your classical art doppelganger. As stated by the developers, it is a way to “connect people to art by way of fundamental artistic pursuit, the search for the self . . . or in this case, the selfie”. Due to the evolution of technology, the platforms which we use to engage with art are changing more than ever. In 2016, Dr Ahmed Selim from Trinity’s CONNECT centre created a software that turned selfies to portraits in the style of famous artists. “The machine is being taught to do the job of the painter”, stated Selim. Whether or not that is a desirable outcome for artists, it is discerningly true that we are constantly searching for representation of ourselves within art.

Artist Tom O’Dea, who is also a researcher at Connect, was shortlisted for the Hennessy Portrait Prize last year for a work that comprised of his own decoded single nucleotide polymorphisms copied on endless scrolls of thermal print paper. Speaking to The University Times, the artist discussed how his piece commented on the relationship between a supposedly very accurate techno-scientific portrait and the actual person themselves: “DNA can represent certain aspects of a person’s physicality but not the complete picture, there’s always a subjective element to it.” The subjectivity of self-portraiture even in a set scientific framework continues to create discourse. We strive to exist as ourselves in other models, numerical data and representational systems.

There is autonomy in the self-portrait. It is a living art form and a cultural institution of the 21st century, concealing, revealing, affirming and capturing an essence of whatever the artist wishes to depict of themselves. Choy-Ping Clarke Ng sums it all up in an allusion to Kearney’s 2016 work: “I’m a Microsoft Paint man in a masterpiece world.” The desire to foster a representation of oneself is conducive to our own personal mythology, whether that may be through means of artistic endeavour, scientific analysis or even the cultivation of social media presence.