Despite years of media attention on high-profile brain injuries, relatively little, still, is known about the long-term impact of concussions. “During a concussion, we don’t know what happens in the brain”, says Prof Matthew Campbell – one of many Trinity-based researchers focused on tackling the threat of brain trauma facing athletes. Some are calling for severe restrictions to be imposed on contact sports. But behind all of the thinkpieces and punditry, Trinity’s scientists are seeking some clarity about these injuries.

“It’s coal-face-type research in that there are so many more questions than there are answers”, says Campbell, who has been instrumental to furthering the study of head trauma in Ireland, establishing the Concussion Research Group with Dr Colin Doherty in 2015 and working closely with MMA fighters and amateur rugby players in search of an accurate diagnosis and successful rehabilitation of those injured. His team carries out a number of tests, including blood tests to look for biomarkers suggesting damage to the blood-brain barrier, before and after a player has played a full season, in order to correlate the results and subsequently form a diagnosis. This is crucial because there is “no standalone technique that can really diagnose a concussion”.

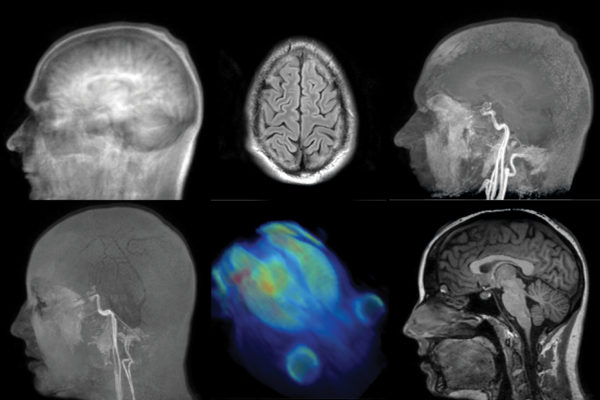

The search for an accurate diagnosis is a focus of the majority of studies into concussions, as scientists look to improve on the current symptoms-based method. “It’s a very difficult diagnosis at the moment, you’re just going off the symptoms and there’s very few hard markers”, says Dr Fiona Wilson, a leading figure in Irish neurology. She adds that “obviously a CT scan is no good”, as there are no specific markers to show definitively whether or not a concussion has been sustained.

Behind all of the thinkpieces and punditry, Trinity’s scientists are seeking some clarity about these injuries

Although Irish research and education regarding concussions have advanced in recent years, the conversation surrounding chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) has largely fallen behind. CTE is a neurodegenerative disease that arises from multiple head injuries. Its symptoms can often include depression and mood swings. “When I go to America, everyone knows what CTE is. You don’t get that here, nobody knows what CTE is”, Campbell tells me. The disease may be rare, but it has become a prominent topic surrounding American football and other contact sports following the suicide of Tyler Hilinski, a star college quarterback, in January. He was diagnosed with stage one CTE post-mortem and may have been battling depression as a result of the large number of sub-concussive hits that he dealt with playing football for Washington State University. A particular concern with CTE, according to Campbell, is that the issue may not be with singular cases of concussive events, but rather with “the nature of the game”. While once-off concussion undoubtedly has a negative impact on the athlete’s health, repetitive head trauma may pose a similar risk, and may be much more difficult to prevent.

Above all, the research teams in Trinity stress the fact that they are not looking to prevent athletes from competing in contact sports. “I think the risk of not participating in sport is likely to cause you an awful lot more health problems than participating in sport”, explains Dr Eoin Kelly, a researcher working with Campbell. The goal is not to prove that certain sports are simply too dangerous to be played, but rather to ensure that a safe amount of time passes following a concussion, or numerous sub-concussive events, so that long-term damage is minimised. Wilson believes that there has been an excessive focus on the negative effects of sport on the brain in recent years, stating that her team is also looking into the “positive effects” of exercise on the brain.

Gregory Tierney, a PhD candidate working with Dr Ciaran Simms of the engineering department, recently released a report containing suggestions for tackling techniques to reduce the risk of brain injuries. Through video analysis and computer modelling of tackles from Leinster senior team players, Tierney and his team found that approximately 60 per cent of concussions in rugby were sustained from tackles and that “it was actually the tackler that was receiving the concussion”. From this data, they found that the safest tackles, from the perspective of reducing the risk of inertial head loading, are those made to the “lower trunk” – the area around the player’s centre of gravity.

When I go to America, everyone knows what CTE is. You don’t get that here, nobody knows what CTE is

Perhaps most notably, all of the researchers praised the professional bodies and the athletes participating in the studies for their enthusiastic engagement with the study. After years of teams and athletes looking to get back on the field faster than the recommended rest time, it seems that the attitude of the sporting world is starting to change. “From a performance and financial viewpoint, that just makes no sense for the clubs”, says Tierney, referencing the fact that the performance of athletes directly following a concussion drops by around 30 per cent. Wilson’s research has also been supported by representative organisations, most recently Rugby Players Ireland, the representative body for current and retired players. The women’s rugby teams have been particularly involved in her research, a crucial element as so many of the current studies are focused on men’s teams. “Part of that is because women haven’t been professionals for as long as men”, she explains. “But it doesn’t really matter, they’re still playing at a similar level.”

Involvement from these clubs, such as Leinster Rugby club and Dublin University Football Club, is crucial due to the amount of data that needs to be collected to reach significant results from these studies. With the number of variables that weren’t accounted for in many cases before, Wilson cautions against putting too much emphasis on past results, adding that “only when we have a big group of people that we follow for a long period of time can we filter out” cases where drug abuse, or a family history of dementia, may have led to long-term consequences otherwise associated with brain injury.

Despite this, many researchers argue that professional leagues are not the ones that should be targeted in studies related to concussions and CTE. Campbell believes that while injuries to professionals are just as serious, players like Sexton “have their own team physicians – they’re getting the support they need”. Amateur and semi-professional players, on the other hand, are at a much greater risk of the long-term consequences of concussions – “it’s a different story when you’re talking about a Saturday afternoon on a random pitch in Dublin where a kid gets knocked out and everyone is scrambling, going ‘what should I do?’”.

I think the risk of not participating in sport is likely to cause you an awful lot more health problems than participating in sport

There is still a long way to go before even a clear method of diagnosis is found, let alone methods of reducing the time players spend on the sidelines following a concussion. But researchers remain confident that the risk of such injuries can be reduced by work such as that of Simms and Tierney, while studies continue to find out more about the long-term impact of head trauma. “We’re only kind of at the tip of the iceberg at the moment”, admits Wilson. Until more accurate diagnosis methods are found, Campbell says, there remain few options available to players potentially suffering from concussion, except to obey the old maxim: “If in doubt, sit them out.”