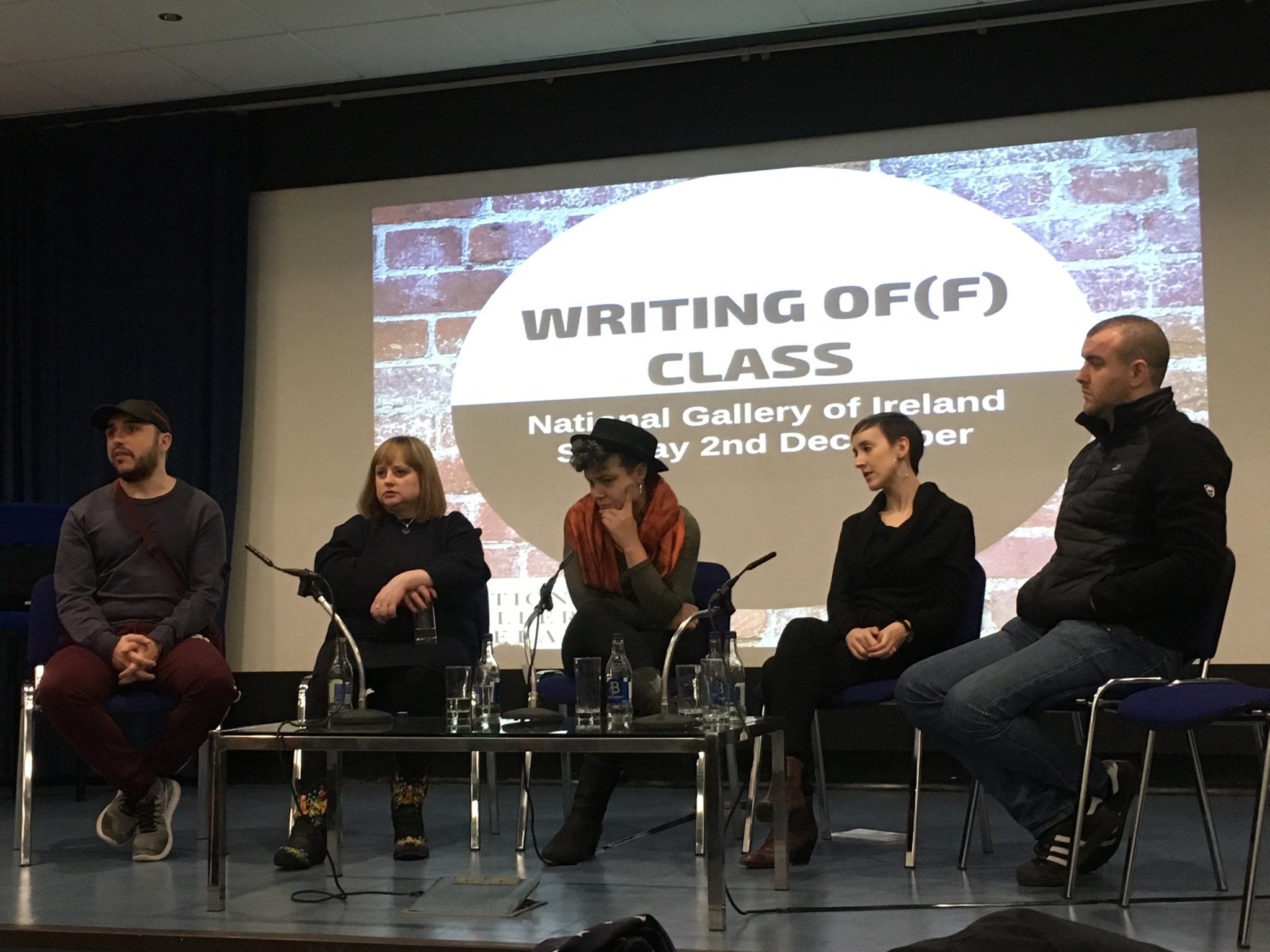

An eclectic panel of Irish artists came together at the weekend for an impassioned dispute on the issue of class in Irish society today, in what was the closing event of this year’s Jonathan Swift Festival. Over the course of an hour and a half, the panellists gave moving accounts of the impact class has had on their development as young people and as artists. The panel boasted poets Stephen James Smith and Jessica Trainor, writer Frankie Gaffney, musician Jess Kavanagh and author June Caldwell.

“If it’s for monetary gains, just don’t do it”, was Smith’s take on working in the arts. Smith has been instrumental in the rise of the spoken-word scene in Ireland today and is one of the nation’s best-known poets, appearing at high-profile events and venues like Electric Picnic and the National Concert Hall. Yet, after a three-week marathon tour of the UK performing his poetry, when expenses were considered, he barely made minimum wage. The glitz and glamour of being a poet is wonderful, but glamour will not subsist you. Smith also bemoaned the paltry conditions writers must accept when seeking publishing deals, emphasising that a good deal of money doesn’t filter down to the artist, and that he’d likely make more money self-publishing.

Also up for debate was the current literary culture in Ireland, from the actions taken by the government to support and fund the arts, to the impetus and deception of reviewing culture. Caldwell, who works as a full-time carer for her mother, explained how her dole payments were cut to almost €30 a week because of a perverse writer’s scheme implemented by the government, which assumes – incorrectly – that the odd week or month of decent income a writer receives, say, for a book being published, is consistent throughout the year. Caldwell also raised the point, often repeated in the cultural scene in Ireland, that if the government wants to revere the writers of the past, it should support the living artists too. The level of funding the government supplies the arts is a brambled and divisive topic, but the panellists were resolute: nothing near enough is being done.

Gaffney, who has risen to prominence recently following the release of his debut novel Dublin Seven, was the most outspoken of the panellists. A self-described communist, he claimed that “class is the final frontier”, now that gender and race have been given such a prominent place in our public consciousness. Gaffney also claimed that “the left had abandoned and betrayed the working class”. Gaffney’s polemical rhetoric even extended to the reviewing culture of Dublin today. When the moderator Sarah Cleary asked the panellists what changes they would make to Dublin art life, if given a magic wand, Gaffney responded that someone needs to blow up the reviewing culture, citing for example that very often it is necessary to pay for your own book to be reviewed.

However, such a hefty dole of pessimism was supplemented with an equal, if not stronger, devotion to art. Smith interceded and told the story of a fifteen-year-old boy who he mentors, and the exceptional poem that he wrote, in which a son comforts his widowed mother with the words of his dead father. The change this anecdote brought over the room was palpable. Disillusioned though we were, with our newfound awareness of the financial strain faced by so many Irish artists, some small weight had been lifted, and there was a feeling that at the very least, this, this was the purpose of art.