The relationship between people and place is a complicated thing. Every village and every poky town, with its own nuances of slang and subtleties of accent, seems to have a strange hold over the people who live in it, a unique identity particular to itself. But in other ways, many small towns have a dispiriting amount in common. Their economic health has a serious impact on the way locals view themselves, and the psychogeography of some is coloured by years of neglect. Many people in small towns feel held back, and left behind.

It’s probably fair to say that the town of Arklow, in Ireland’s south-east, falls into this category. Untended and often overlooked, Arklow is a place creaking with its own sense of nostalgia. Many of the locals here are steeped in the proud but evanescing history of its once-thriving maritime, pottery and shipbuilding industries. Many of the more knowledgeable residents of this area would think it wrongheaded to look beyond these core industries in any pursuit of the essence of Arklow’s identity.

Arklow’s coat of arms – a fish and a golden potter’s plate in either corner – highlights this aspect of its history. Both emblems soar high above a magnificent, sailing ship. But what becomes of these symbols when the place they represent no longer possesses the strength and power embodied in them? Do the inevitabilities of urbanisation and decay experienced by a town like Arklow ultimately render them meaningless?

It is this uneasy realisation that Arklow still seems reluctant to come to terms with. Local fishermen working at the town’s docks complain, with what seems like some justification, that globalisation has sabotaged their time-worn traditions. And it’s hard to disagree: in the last five decades, the number of fishing boats in Arklow has fallen from between 80 and 100 to a meagre 14. The fishermen don’t want to give me their names, but one tells me that “Arklow Bay, once famous for its mussels and herrings, as well as white fish and prawns, is now reduced to whelking only. This is due to the overfishing of Arklow’s waters. 80 ft trawlers, hailing from Spain, France, and England, swept in and took all the fish. Now there is no net fishing here at all. The trawlers are long gone. Everything we catch is export only: our haul is transported to Kylemore in Wexford where it is processed and then shipped to China, Japan and South Korea”.

It’s a paralysing set of circumstances to work under, and barbs like “the EU is a load of balls”, and “Irish politicians don’t give a damn about working people” make it quite clear who the fishermen blame.

Pockets of investment, in the form of the town’s Goldman Sachs-owned Bridgewater shopping centre and a proposed Datapac centre, offer glimpses of promise, and in relatively recent times the town has seen injections to the local economy in the form of KFC, McDonald’s and Tesco. But if these businesses bring jobs to the area, their presence also exacerbates the troubles plaguing a cluster of home-grown Arklow businesses already fighting for survival.

So long as the kinds of enterprise that Arklow attracts are of multinational stock, it’s unclear, on a cost-benefit analysis, that the obvious good of new sources of income for many employed by the corporations is not outweighed by the negative impacts visited upon local businesses by the new big-shots in town.

What the town desperately needs is somebody who will at least try and shake things up and get things done on behalf of Arklow

It’s clear that chronic political abandonment is at least partially responsible for Arklow’s current predicament, but some local politicians are fighting in political channels to reverse these grim trends. One of these is local independent councillor Peir Leonard, an artist who tells me that “things are starting to improve, but, you see, it requires people to take things into their own hands sometimes and push their ideas forward”.

Leonard, elected for the first time in Arklow’s 2019 local elections, says she was motivated to run for office by a DIY attitude and a dedication to improving Arklow’s fortunes by refusing to kowtow to party politics. “I want to help people and the town to flourish”, she says. Leonard runs a local pottery studio, Solace, which she says “is about bringing them to the forefront and encouraging people to believe in themselves”.

Solace is rapidly becoming a vital outlet for Arklow’s creatives, in a town once fuelled by the pottery industry. It offers a space for local artists to express themselves, and for young people and people with mental health issues to actively participate in the continuation of Arklow’s ceramic heritage.

Peir Leonard, an artist and local politician, runs a local pottery studio in Arklow.

Leonard believes that fostering an entrepreneurial spirit in the Arklow people, especially its youth, can go a long way to rejuvenating the town, but insists this spirit must have a communitarian ethos at heart: “People having a bit of get up and go is essential to making a town the best it can be”, she says. “But, for me, it needs to be a form of entrepreneurship with an equally strong social dimension. I guess that’s really what I’m trying to achieve here by putting an idea into action that will, hopefully, benefit the community at large. I’d love to turn this studio, one day, into a place where local artists could showcase their work as part of an exhibition, and maybe even have some of the art for sale.”

The studio, though, offers only a rare glimmer of optimism in a town Leonard believes has been gravely undermined by political representatives who she says favour their own interests at the broader expense of the town itself. She makes no bones about her frustration at the calibre of Arklow’s councillors: “The fact of the matter is that many of the local representatives are too happy just to look after themselves. What the town desperately needs is somebody who will at least try and shake things up and get things done on behalf of Arklow. The area is being let down, and that needs to change.”

In peak times, there would have been around 700 people employed in the pottery

If Solace is a success story for Arklow, then it also serves to highlight in a paradoxical way the rise and fall of one of the most famous aspects of the town’s history: Arklow Pottery. Once internationally renowned, the pottery offers a case study in the difficulties faced by declining industries all over the world.

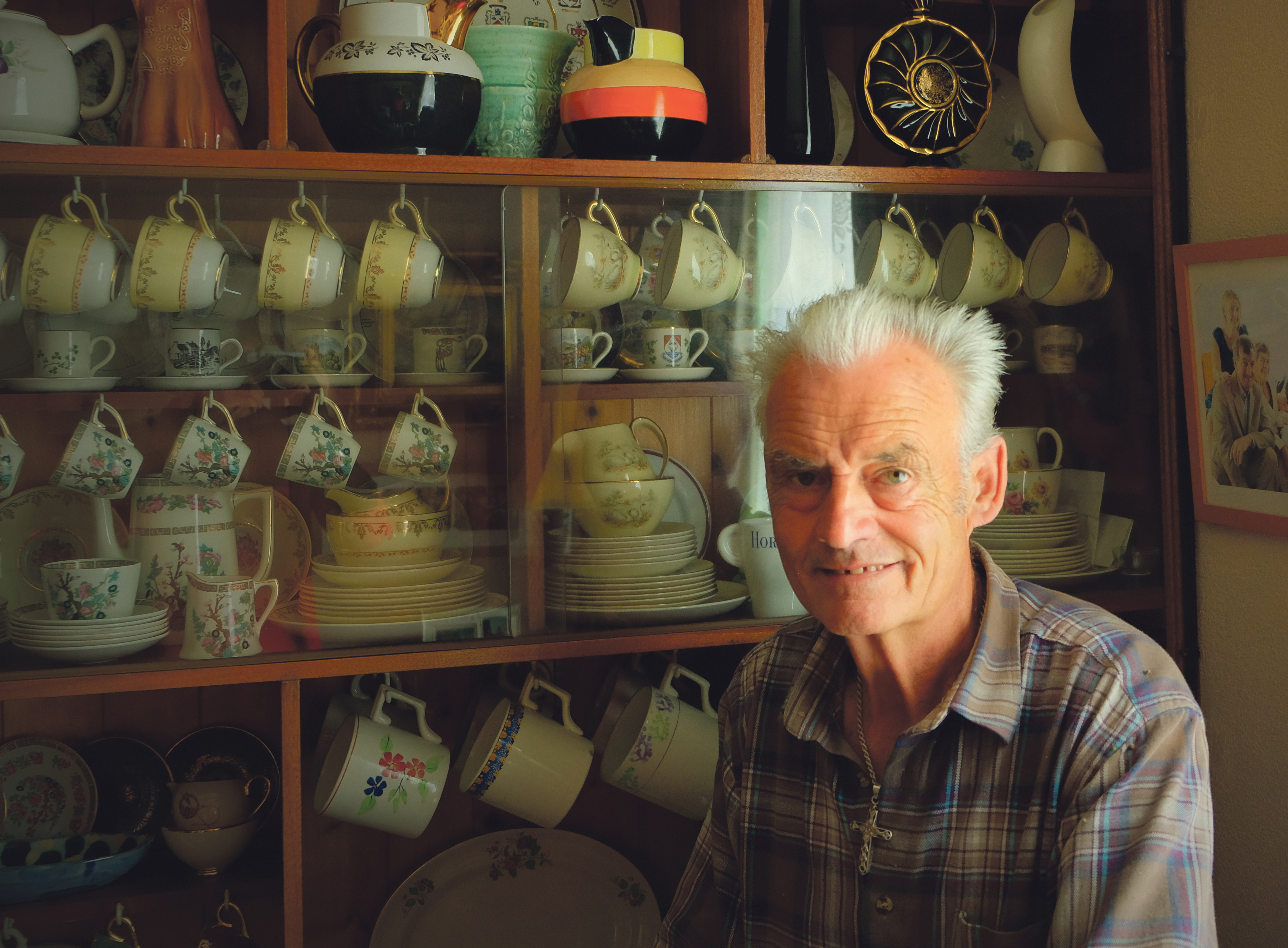

Arklow Pottery was founded in 1934 and formally opened by Seán Lemass in 1935. Its history includes chapters under the ownership of Japanese company Noritake and, in an earlier period, Irish ceramic artist John Ffrench. Local resident Tommy Dunne worked in a casting shop for the firm between the years 1969 and 1973. Dunne’s fond memories of the firm are more than professional: it was through Arklow Pottery that Dunne first met his late wife of 42 years. She worked there, in both the canteen and the packing department, between 1968 and 1978.

Dunne tells The University Times that “in peak times, there would have been around 700 people employed in the pottery. But, in many ways, it became a victim of changing consumer demands. Rather than buying ornate tea sets or saucers and teacups, people started to use big mugs and cheaper items. I suppose that was down to mass production in places like China. The firm here just couldn’t compete. And once you can’t compete – well, that’s when the shutters start to come down”.

Dunne speaks with the fastidiousness of a man who takes great pleasure in doing things with careful precision and attention to detail. Small wonder: he maintains a breathtaking, and eclectic, collection of the defunct firm’s pottery in his home, including a 22-carat gold teapot.

He says of the item that “for a piece like this gold teapot, an application of gold leafing would be used on the surface. Then, some time after the gold has been applied and dried in, all excess gold would be wiped off using a cloth. Following this, all cloths would be burned and any leftover traces of gold would be collected and reused”.

In the last five decades, the number of fishing boats in Arklow has fallen from between 80 and 100 to a meagre 14.

Listening to Dunne as he surgically outlines the production process of such a beautiful piece of artisanship, and reflects on a social setting in which lasting bonds between workers were forged – not least in the case of his own personal life – offers a graphic reminder that the loss of jobs brought about by the pottery’s closure also meant the death of a community stronghold. Families were made, friendships and life-long loyalties ran deep, and, above all, a powerful feeling of belonging was fostered, grown and subconsciously sprinkled over the rest of Arklow’s community: an almost subliminal osmosis born of a town with its head held high.

Besides this, the pottery firm did much more than just provide its directly employed workforce with a livelihood – it facilitated a broader distribution of wealth that local businesses could also share in. Workers from the pottery would spend their wages in the local economy, meaning other, smaller businesses could also feel the immediate benefits of the increased economic activity. If this sounds dewy-eyed, it is a fact evidenced by the custom-made pottery items that were used by certain local businesses within the town, such as Brendan’s Bakery. By linking itself in this way with other integral features of the town, Arklow Pottery embedded itself as a foundational part of life for so many local people in the area.

“It was a craft”, Dunne says, “it really was. This stuff was shipped all over the world: Canada, Australia. The level of skill that went into making many of these pieces is just truly incredible. Many of the pieces would have been used to send as gifts to family members living abroad, in the wider Irish diaspora. But what really killed the pottery here was open markets. It just got to a stage where it wasn’t cost-effective to produce here anymore. It is sad to think about, but great times all the same”.

It’s hard to be immune to Dunne’s sense of melancholy nostalgia or to reject his theory. All over the world, in working-class towns just like Arklow, downhill slumps have often been determined by the imposition of globalisation on local towns.

The logic is simple: as markets become more open to competition, certain firms are outperformed by others. It’s survival of the fittest, a race in which there is always another firm in your peripheral vision, or just over your shoulder, capable of producing faster and at a far lower cost. This is a harsh reality Arklow’s pottery industry came to know all too well. In the absence of any external helping hand or state guardian willing to swiftly intervene in order to protect the industry, extinction was all but inevitable, and it closed in 1998.

Arklow Pottery is a cautionary tale of a company at the nexus of a community being forced into the ground by blind economic factors. Another comes when Dunne tells me that “this was one of the very first local authority houses built in the whole town of Arklow in 1922. I bought this house for £200. In the boomtime, I saw a house sell here at around the €270,000 mark”. The type of inflation Dunne describes, it seems, is the same sort of rapid economic acceleration that has caused so many small businesses to fold.

Arklow, then, gives the impression of a place looking in two different directions at once. Now a satellite town, it acts as a hotspot for slews of workers seeking a relatively short commute to Ireland’s economic heartland of Dublin. This is an association that further reinforces Arklow’s position firmly in the shadow of the capital, showing the yawning chasm separating the commercial hub from the rest of Ireland, even those areas in close proximity to it.

But if the famous Arklow Pottery is now just a memory, then it’s quite a legacy, and its achievements still linger. So maybe the way forward for Arklow lies not in allowing itself to be another footnote of a footnote in the hoarded business portfolio of Goldman Sachs, or an item left on the shelf to expire by political representatives. Maybe Arklow should look back at its former staple industries, and take inspiration as it attempts to piece together the fragments of its identity. Although it is foolish to believe there is a viable future in an exact replica of Arklow’s past, a revival, brought about either by the resourcefulness of its people or by a miracle, is possible – and necessary.