In 2003, then-President of Ireland Mary McAleese formally opened Trinity’s Ussher library. Twelve years later, in 2015, €16 million was allocated to the recruitment of 40 professors as part of Trinity’s Ussher Assistant Professor Development Programme.

Despite Trinity’s copious use of Ussher’s name, however, it seems there is a striking number of us students who know next to nothing of the man behind the name.

Dr Andrew Pierce, an assistant professor of ecumenics and former head of the Irish School of Ecumenics, confirms this: “There was probably something a little forgotten about Ussher.”

So who was he?

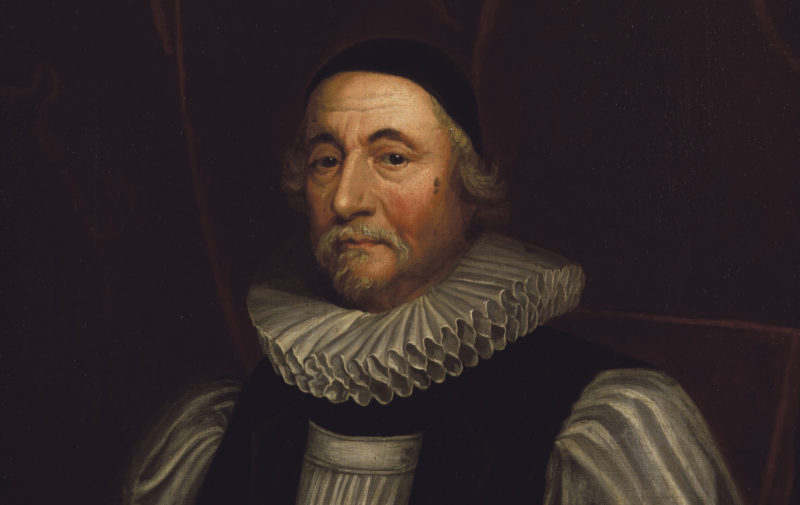

Born on January 4th, 1580 in Dublin, and enrolled in Trinity in 1593 at the age of 13, James Ussher would go on to be appointed professor of divinity in 1607. He was ordained a clergyman of the Anglican Church of Ireland in 1601 and, 24 years later, succeeded his uncle as archbishop of Armagh and primate of all-Ireland.

In the meantime, he dedicated himself to a life of scholarship.

He was a biblical scholar, a theologian, a linguist, and an historian. He was the pioneer of early Irish church history, with a gift for finding and editing previously unknown sources

Alan Ford, a Trinity graduate and retired professor of theology at the University of Nottingham, has studied Ussher for 40 years and is considered the principle authority on his life and work. In an email to The University Times, Ford says that Ussher was a scholar of great significance in his day: “He was a biblical scholar, a theologian, a linguist, and an historian. He was the pioneer of early Irish church history, with a gift for finding and editing previously unknown sources, the author of the first full history of the early Irish church.”

This is a sentiment that is echoed by Pierce. “He was a fabulous linguist and a very fine textual scholar”, he says. Ussher lived at a time when there was an “endless array of textual materials being ploughed through. And being able to do that, and being able to sort of try and be au fait not only with the past but also where the present intellectual agenda is going, that’s an impressive role model”.

Legend has it that Ussher was inspired to embark upon such a life of the letter when, at the age of 12, he came upon a saying attributed to Cicero, which says: “To be ignorant of what has happened before your birth, is to be always a child.” These are fine words indeed, yet they’re ones that, as we will see, Ussher – perhaps unfortunately – failed to live up to, despite what must have been his best efforts.

While Ford might claim that Ussher “was a gentle, scholarly soul, who made hardly any enemies”, there was one group for whom he had little time: Catholics. His disdain for those Christians who professed allegiance to Rome was such that, in 1626, he wrote in his Judgement of the Archbishops and Bishops of Ireland that: “The religion of the Papists is superstitious and idolatrous; their faith and doctrine erroneous and heretical … to give them therefore a toleration, or to consent that they may freely exercise their religion … is a grievous sin.”

In 2003, then-President of Ireland Mary McAleese formally opened Trinity’s Ussher library

Ford, however, dismisses this apparent sectarianism as part and parcel of the world which Ussher inhabited. For many Protestants at the time, “the Pope was the Antichrist and Catholics therefore antichristian”. Ussher, according to Ford, was unexceptional in this regard: “He was not, in short, an ecumenist.”

How does this sit with Pierce, a professor of ecumenics? “Some of his views, obviously you sort of put them in brackets and think: ‘That’s rather scary.’”

Ussher was obviously limited by the times in which he lived. His most famous work is his chronology, which first appeared in 1650 as part of his Annales Veteris Testamenti. It was a mammoth work with the aim of providing the precise dates of significant biblical events, in which Ford says Ussher “painstakingly worked out when the world was created, and came up with a date”.

Thus it was that Archbishop Ussher, nearing the end of a long life of extensive reading and research, was able to claim an exact date for the beginning not only of human history, but of the earth itself: Saturday evening, October 22nd, 4004 BC.

Now, of course, we would scoff at such a suggestion, but both Pierce and Ford insist that Ussher did the best he could with the information available to him at the time.

“In terms of the kind of theology that he did, he was as up to date as he could be”, Pierce says. Ford points out that Ussher “used all the relevant scientific, historical, biblical, astronomical, geographical and chronological knowledge of his day to compute the date of the foundation of the world. If he was alive today, he would do exactly the same, and of course, come to a very different conclusion”.

The religion of the Papists is superstitious and idolatrous; their faith and doctrine erroneous and heretical … to give them therefore a toleration… is a grievous sin

This may be true, and it may even be unfair to ridicule Primate Ussher for the magnificent falsehood of his life’s work. The eminent paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, Stephen Jay Gould, famed for his magnanimity when it came to the conflict between science and religion, wrote in 1991 that Ussher’s chronology was “an honourable effort for its time”. We may grant him this, but it’s also true that we no longer live in a world such as Ussher’s.

Ours is a world informed by the works of Einstein, Darwin and Hubble, and entertaining the idea that the earth is a mere 6,015 years old is no longer possible. This may seem painfully obvious, but recent polls in the US have shown that some 19 per cent of respondents still state the belief that the earth was created on the day named by Ussher. He may have been a brilliant scholar, but for many people beyond the walls of Trinity, his chronology is his legacy.

This begs the question: should Trinity, an ostensibly liberal and progressive institution of education and research, be celebrating someone so closely associated with the kind of stultifying ideas to which we should be fundamentally opposed?

Both Pierce and Ford support the College’s lionisation of Ussher and counter my reservations by citing examples of other problematic figures whose names have been used in similar ways. Pierce references Georgetown University’s renaming of buildings in an attempt to atone for their legacy of slavery: “That was a very interesting debate. They had a facility named after someone complicit in the bad days, and therefore what do you do with it? Do you try and keep it there? It’s a bit like the Rhodes statues.”

This, however, is missing the point when it comes to the Ussher case: Trinity was not stuck with a library named after Ussher – it waited until the 21st century and then named one after him. It then waited another 12 years to name the assistant professorships after him, while in the interval his work was being published by creationist presses and his ideas lauded by the likes of answersingenesis.org and the Institute for Creation Research.

Recent polls in the US have shown that some 19 per cent of respondents still state the belief that the earth was created on the day named by Ussher

It is easy to say that Ussher’s work has been wrongfully appropriated by creationists wishing to twist it to their own ends, but really this argument doesn’t stand up.

As Pierce himself points out, Ussher’s chronology has been “a persuasive tool in the Bible Belt” since it was used in the 1917 edition of the Scofield Bible. Prior to this, according to Pierce, it had been “taken up and given widespread acceptance amongst many protestants by another TCD graduate – less well known, but of dangerously wide influence – John Nelson Darby”.

Darby is credited as the father of modern dispensationalism – the idea that the end of the world is approaching, and things will get worse and worse until it’s here. It’s important to remember, of course, that Ussher didn’t try to predict the end of the world, but his work has nevertheless proved instrumental for those who have, and for those who continue to do so. Creationism has its roots, Pierce tells me, in the changing attitudes towards the interpretation of the bible that came about in the wake of the Renaissance and Reformation. “Ussher was there at the beginning of all that”. he says.

Therefore, Creationists haven’t found Ussher and retroactively adopted him to their cause – it was the other way around. The proliferation of his work arguably gave rise to the movement. “That creationism has since become more marginal and less intellectually respectable”, Ford argues, “is not something we can blame Ussher for”.

Perhaps not, but it’s hard to see it as merely an unfortunate offshoot of Ussher’s otherwise noble work.

Pierce likens Trinity’s celebratory use of Ussher’s name to the scientific community “getting excited about Newton, and yet he’s part of that alchemic-mystical whatever it is. We wouldn’t dismiss him, but we would want to try to remember him in something of his complexity”.

Indeed we would, and we do.That Isaac Newton was a devoted student of alchemy is common knowledge, as is, to a slightly lesser extent perhaps, the fact that he too shared Ussher’s interest in biblical chronology. What differentiates him from Ussher are his other contributions, which have had a significant and lasting impact on science. Newton is celebrated in spite of his more infantile ideas, which, for the most part, he had the good sense to keep secret during his own lifetime. Can we really say anything of the sort for Ussher?

The College’s Manuscripts and Archives Department may have access to documents that might have shed light on the decision-making process that led to Ussher’s name being chosen. Unfortunately, such papers are not given to public access until 30 years after their issue. The department does, however, maintain that “it goes without saying that Ussher is an obvious choice for the name of a library building here in TCD”, citing the contribution of his manuscript and book collection to the formation of Trinity’s library stock.

Again, this leaves us with the same question: why did they wait so long? Ussher died in 1654. Trinity waited some 350 years to give his name the kind of platform it now has – 350 years during which many of his most influential ideas were conclusively debunked.

One is therefore forced to pose the question: was there really no-one more deserving of the honour that has been bestowed upon James Ussher? Of all the thousands upon thousands of students and scholars who have gone before us, is it really the case that none were more worthy of having their name immortalised in the manner that his has been?

It can, you would hope, be assumed that the naming of the library and assistant professorships was not a decision that was taken lightly. Several candidates must have been considered before a final decision was reached. Those who settled on Ussher must have thought that his work constituted a worthier contribution to academic and cultural discourse than that of any other possible candidate. They must have believed that to venerate him and his work was a suitable representation of the views and values of our university and those who people it.

And seemingly, some still do. In the recent past, Pierce tells me, celebrations of Ussher of a very different kind took place in Trinity.

“Whenever the world was having a significant birthday according to Ussher’s chronology”, he tells me, “they had a special breakfast party in the Common Room for him. So there were various people having a lovely breakfast, and singing happy birthday to the world”.

Whatever its intention may have been, Trinity’s use of Ussher’s name – a straightforward commemoration – seems to neglect the nuance of his contributions. Special breakfast parties in the Common Room might be a more suitable commemoration for someone with a contested legacy such as Ussher’s, and allows the minority community who wish to celebrate him to do so in an environment that allows for the irony suggested by Pierce.