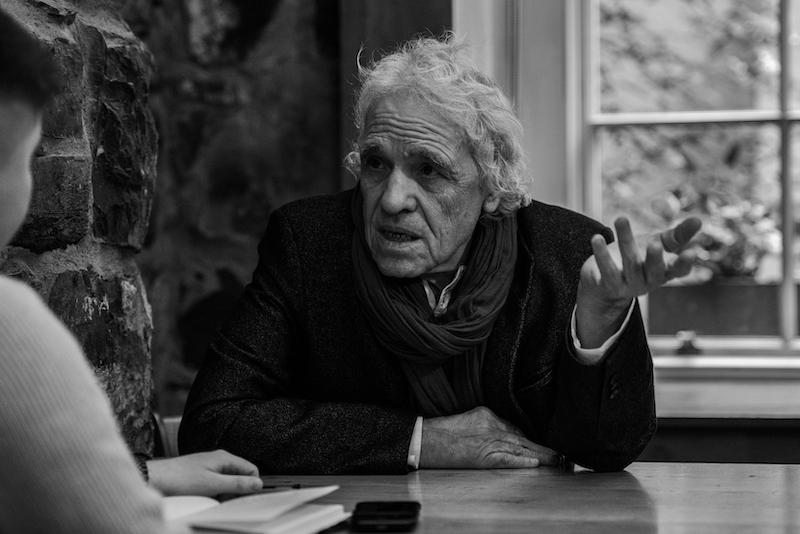

Abel Ferrara is as you’d expect: difficult and unpredictable. My photographer and I are still setting up for the interview when he enters. We are taken by surprise, and it shows. “Don’t look at me like I’m a freak”, he says. I get the sense that Ferrara’s a little prickly before we begin. My interview with him was his first of three. That evening he was to do a question and answers session in the Irish Film Institute (IFI) after a screening of his latest feature, Tommaso (2019), and the following day he was to do a masterclass in Trinity.

Naturally, my first question is about Tommaso. “The film seems autobiographical”, I begin. “Did you see it?” Ferrara asks. I hadn’t – that night was its Irish premiere. “Why do you want to talk about a film you haven’t seen? Are you going to see it?”, he asks. I respond: “Yeah, but I can’t tonight, I’m going to a wedding.” He asks if I’ve seen any of his films, and I tell him I’ve seen Bad Lieutenant (1992) and Pasolini (2014). “Oh, all right”, he replies, irritated.

Since we can’t talk about Tommaso, I ask him – and the wording here is crucial – if he finds himself “revisiting old themes or similar themes”. He responds: “Why would I revisit the same themes or similar themes?” Plenty of artists do this, Scorsese in The Irishman (2019) for example, but I let him talk. “I’m an artist, I’m a fucking creative person.” I try to say something, but he cuts me off. “Here’s my question to you – I hear you make the same bullshit movie every time?”

“I didn’t mean to be offensive”, I start. He groans. “You’re not being offensive. You didn’t see the fucking movie that we’re showing, OK. So that’s a drag, I want to talk about my new movie. You didn’t see it.” I interrupt him now: “It’s not my fault it hasn’t been shown here.”

“It’s their fault”, he tells me, presumably referring to the festival’s organisers. He’s clearly angry. “You can’t come tonight because you’re going to a wedding. That’s how much you care about seeing it. Let’s take it from another point. You saw Bad Lieutenant – that’s a film that I made 100 years ago. I don’t even remember making it. You want to talk about that?”, he asks me. “We can talk about Pasolini then”, I retort, beginning to lose patience.

I want to talk about my new movie. You didn’t see it

“We can talk about the future. You got me in front of you – ask me something you really want to know the answer to”, he demands.

Honestly? “Was it for money, for art or for the sheer cuckoldry of it that you cast your girlfriend in your porno 9 Lives of a Wet Pussy (1976)?” But I don’t say this. The more sensible part of me, or perhaps the less courageous part, asks something more vanilla: “Where do your ideas come from?”

“That’s the number one question I get asked”, he responds, finally cracking a smile of sorts. Ferrara finds it too difficult to answer. A waitress interrupts us, placing a litre bottle of sparkling water on the table. “You want some sparkling?”, he asks. I don’t. “You want a Guinness?”, he jokes. “Hey Carla, these guys are driving me crazy”, he shouts at the festival’s organiser – there’s a humour to his tone now.

The interview calms down after these opening two-and-a-half minutes. Ferrara begins talking about his documentaries. He describes making his first one in the late 2000s as “a revelation. It’s less structured and the shooting of it’s easier. You’re going after knowledge, you’re not going from a point of something that you’re trying to recreate”.

He says he began using more documentary techniques – “long free-flowing takes, not using actors but using real people” – in his subsequent features. He’s getting into his groove now, becoming more relaxed, swinging and swigging his glass bottle about.

Ferrara delivered a masterclass in Trinity as part of the Silk Road Film Festival.

Ferrara moved to Rome from New York in 2003 because he found it easier to get his films funded there. New York, he says, “changes every minute”. He elaborates: “I think my town has been ripped off, man, but I don’t know by who – Wall St international brokers, real estate guys, whatever. My New York is downtown Manhattan and it’s been totally co-opted. I don’t want to pay 10 dollars for a tomato.”

His Irish heritage comes up. I ask him – if it’s not too corny – to talk about it. “Considering you haven’t seen the movie, you have to ask something”, he says. Then he asks: “Who’s getting married?” I tell him who’s getting married, and that I’ll be at the masterclass tomorrow. “Still haven’t seen the film”, he chuckles.

Ferrara’s mother’s maiden name was O’Brien. She was “born in the Bronx, very poor family. She didn’t talk about it. But she was Irish, blonde hair, blue eyes, as Irish as they come”. He enjoys the election posters throughout Dublin, describing them as “old school”. He’s bemused by the posters: “Just stick it on a telephone pole? I mean, c’mon – what is this, some kind of fucking second-world shit? Do these guys work social media too?”

Just stick it on a telephone pole? I mean, c’mon – what is this, some kind of fucking second-world shit?

Ferrara is hesitant to reveal too much about future projects. “It’s not easy putting these gigs together, so I’ve three or four things in mind.” After a pause he elaborates. “I want to do something on the election in the United States. Some kind of documentary, maybe a docudrama, following a journalist who’s following the election.”

He says he’s “looking for a woman” to be the next US president. More specifically, he thinks Elizabeth Warren is the woman for the job. He hopes the nominee isn’t somebody like Biden, explaining that “these guys were all there and so they’re the reason Trump is there. I mean this is what Trump ran against, career politicians”.

Ferrara holds a special disdain for Trump. “A guy like Trump, he’s from my generation, he comes from where I come from. You really don’t get what a motherfucker this guy really is. If you could really understand the words he uses, his body language – if you knew this guy.”

I feel like I understand Ferrara a bit more by the end. He’s arrogant and charismatic, and whatever disdain he was showing at the start was an artist’s pent-up frustrations. We talk a little after the interview, off the record, which is cool. At the masterclass he even asked me about the wedding. Everyone laughed when he mentioned I couldn’t see Tommaso – including me.