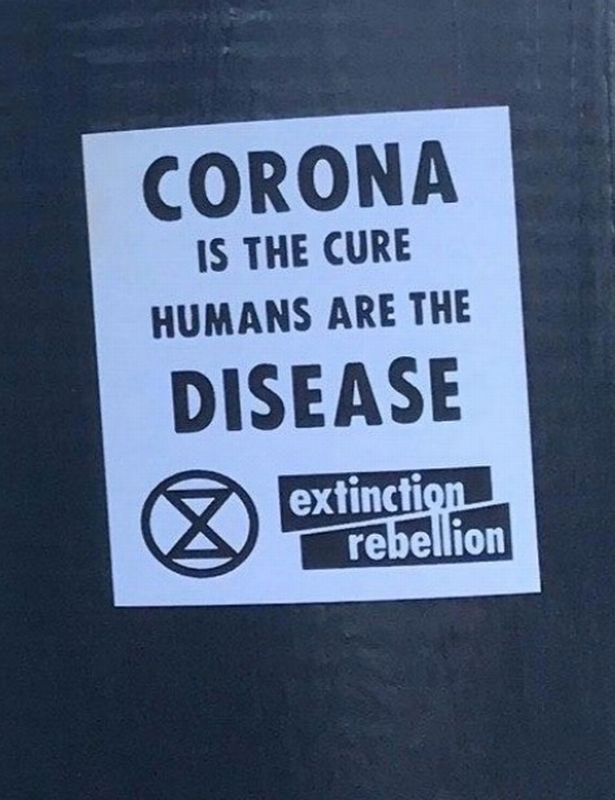

In late March of this year, amidst the global confusion of Covid-19 lockdown, a smattering of posters with bewildering messaging appeared in locations around London. Bearing the recognisable graphics of eco-activist group Extinction Rebellion (XR), the posters stated: “Corona is the cure. Humans are the disease.”

The contempt for human life in these words starkly opposes XR’s customarily compassionate approach to the crises currently being faced by humanity. This anti-human sentiment provoked hordes of regional XR groups including Extinction Rebellion Ireland to come out in vehement opposition. The posters were also accompanied by similar posts on a Twitter account purporting to be run by XR East Midlands. It soon transpired that no such group existed within the organisation, and that this was the work of some other person or group with a disturbingly dark agenda of their own.

It may not be immediately apparent as to why the suggestion that humans are some sort of scourge on our planet is so troubling. In fact, many people not well-versed on the nuances of the issue might take one look at the catastrophic damage our civilisation has inflicted upon our natural environment and be inclined to agree. This is why viral tweets with statements such as “We are the virus” and “Mother Earth is cleansing herself” accompanied by doctored images of dolphins swimming in the canals of Venice gained such traction with so many people: it is easy to accept that we as humans are causing big problems. Yet this over-simplified conjecture misses so much of the truth: it’s not simply “humanity” that’s the problem.

When sentiments likening human beings to a deadly virus become normalised in popular culture, then we know we have a problem looming

Speaking on the phone to Memet Uludag, Irish national organiser with the United Against Racism grassroots network and a trade union activist, I ask for his take on this issue. He confirms where the real problem lies: “This destruction is the making of the capitalist system. It’s not ‘people’. The problem is how our means of production are organised. So right now we have the huge fossil fuel energy industries making profits by destroying the world and its ecosystems.”

Memet agrees that the appearance of these posters and the wider anti-humanity narrative emerging in the wake of Covid-19 shines a light on a very shadowy underbelly of environmental discourse. It is precisely the type of socio-political trend to put the United Against Racism network of activists and educators on high alert, as they devote themselves to opposing racism and fascism in all of their forms.

The concern seems to be the insidiousness of the messaging – the mind does not readily link environmental discourse to fascism. While mainstream environmental thought is generally situated staunchly on the left-hand side of the political spectrum – you may read: hippies, socialists, and most Arts Block students – there exists another paradigm within the green movement, one which does not consider all lives to be equally worthy of environmental justice.

Eco-fascism is the term used to refer to far-right environmentalists who buy into this idea that humanity, or certain minority groups, deserves what befalls it. As the climate crisis escalates global feelings of fear and societal instability, eco-fascists are those environmentalists who respond to this reality with xenophobic and nativist ideations.

Sincere in their environmentalism, their view of the green solution involves something like “severing the extra hands that cling to the side of the lifeboat” so that those lucky enough to be already on-board have the best chance of survival (an infamous quote from Finnish deep ecologist Petti Linkola).

In this way, Memet warns, “rather than dealing with the root cause of environmental destruction, [eco-] fascism wants to use it to advance its own agenda… a hierarchical vision of society. They want to preserve the preferred ‘old way’, the lifestyle… To do this, they think they have to sacrifice others: poor, migrant, black, the Mexicans at the US border… all horrible racism and authoritarianism of course.”

An eco-fascist group masqueraded as Extinction Rebellion to spread its anti-humanity message.

The image of the lifeboat is probably one of the most politically charged of our time due to the thousands of lives lost in the Mediterranean since 2011 as a result of the Syrian refugee crisis (which is linked to the impacts of global warming). The lifeboat as a familiar symbol of the effects of EU nationalist border policies resurfaces in Linkola’s eco-fascist creed, which is cited enthusiastically by proponents of eco-fascism all over the world, especially rampant in anonymous online forums such as Reddit. This refugee crisis is a real-time example of eco-fascist ideology playing out in national politics: eco-fascists don’t think that we all deserve a lifeboat.

And yet, “climate change will be and already is a huge global driver of climate refugees”, asserts Memet. This is a point he returns to repeatedly during our conversation, highlighting the status of climate refugees as another big cause for concern: “They will be one of the core aspects for a just transition – we must keep them as a focus. We can’t give the far right the platform on this, setting the narrative. Their choice will be to let refugees die, militarise borders… rather than deal with the systemic cause of all of this.”

How is it that eco-fascists rationalise their ideas, justifying the death of others as something necessary to save what they consider their environment? One way is with the much-touted “human overpopulation” argument, which goes something like this: there are too many people on the planet consuming too much carbon and eating too much food, which is why we are experiencing a climate crisis.

This is based on what is called Malthusian theory, a theory of population growth that was first put forward by Thomas Malthus in the late 18th century, positing that population growth was exponential while food supplies were linear. While the theory has since been repeatedly disproven, its influence remains. Add eco-fascism’s hierarchical and xenophobic vision of society into the mix, and the argument’s insinuation becomes incredibly distressing. Following along the trajectory of this dubious ideology, the question quickly becomes: what is the solution to this supposed problem of “too many humans”?

Fascist white supremacists believe that certain groups in society have less value, pinpointing vulnerable minority groups such as migrants, the elderly, people with disabilities and the poor. Fascism’s ugly history screams warnings of “never again”, but still we see the ideology weaving its way into everyday discourse until barely recognisable, obscured in memes on social media or hidden in the shadows of reputable environmental branding. When sentiments likening human beings to a deadly virus become normalised in popular culture, then we know we have a problem looming.

Environmentalists say that human beings are not the problem – instead, the big fossil fuel companies need to answer for climate change.

Those proponents of the overpopulation argument for the environment are generally seeking to prop up an outdated capitalist system that serves the few while failing to acknowledge that those currently bearing the brunt of the climate crisis – such as the millions displaced in Bangladesh this year due to catastrophic flooding – tend to have the lowest carbon emissions and consumption patterns (according to a 2015 study by Oxfam).

It goes without saying that anyone making this overpopulation argument is highly unlikely to be a Bangladeshi flood victim, and much more likely to be a carbon-addicted Global North consumer with two cars and a penchant for online shopping sprees. From this perspective, the xenophobic undertones in “overpopulation” rhetoric are hard to miss.

Eco-fascism is not a new threat, just a re-packaged one. Its roots can be found in Nazi Germany’s “Blood and Soil” ideology, which claim that blood or ethnic identity is inextricably tied to native soil, and any threat to this order must be challenged. Huge focus was placed on German land as something to be revered and protected by and for Germans. Modernism and industrial society were seen as opposing their nativist ideals, and this became a premise upon which the Nazis justified the genocide of Jews, whom they viewed as symbols of this consumerist culture, threatening the “old ways”.

As modern-day peace’n’love environmentalism emerged with the Hippie Era of the 1960’s and 70’s, eco-fascism was also experiencing a quieter but more deadly peak. Overpopulation theory was beginning to go mainstream, largely as a result of the publication of a book Population Bomb by Paul Ehrlich in 1968.

In his book Ehrlich blamed many of our societal woes on population growth, and advocated for sterilization as a solution. His work was influential on ecofascist thought, and drew inspiration from the debunked Malthusian theory. Even in the early 1900s fervent ecological conservation efforts made by wealthy white Americans such as the white supremacist and eugenicist Madison Grant reveal the omnipresent overlap between environmental concern and fascist ideology. Grant was the founder of California’s first redwood and wild buffalo conservation organisation, president of the Bronx Zoo and author of The Passing of the Great Race, a book Hitler referred to as his personal bible.

It goes without saying that anyone making this overpopulation argument is highly unlikely to be a Bangladeshi flood victim, and much more likely to be a carbon-addicted Global North consumer with two cars and a penchant for online shopping sprees

This toxic legacy continues to emit its shockwaves on our modern-day society: Anders Breivik, the Norwegian far-right terrorist who massacred 69 young people at a summer camp in 2011, cited Madison Grant’s racial theory in his manifesto. The Christchurch mosque shooter Brenton Harrison Tarrant, who murdered 51 people in May 2019, is a self-proclaimed eco-fascist. Patrick Crusius, the terrorist who shot and killed 22 people in El Paso, Texas in August 2019, was inspired by the Christchurch events. Much of Crusius’ manifesto was dedicated to Ehrlich’s theories, indicating a fear of overpopulation and subsequent decimation of the environment as his motive for mass murder. This is no benign political trend.

Speculation has it that the culprits behind the false XR poster campaign are a far-right group called the Hundred-Handers. They are a low-level activist group with anonymous membership that have been accused of masquerading as XR UK in the past. Their main tactic appears to be stickering up hate messaging in public, preying on fears instilled by world immigration politics and the coronavirus pandemic.

It would certainly be easy to write them off as a group of dim-wits hiding anonymously behind computer screens and putting weird stickers on lampposts, but they are much more dangerous than that. As Chinese Taoist philosopher Lao Tzu put it: “There is no greater danger than underestimating your opponent.”