Trinity’s ladies’ toilets hold a secret which is little more than an open one: desperate messages ranging from “try this website for safe abortion pills” to “text this number after 8pm for support” are tagged on its doors. There is a tacit agreement between the toilets’ users and the cleaning staff not to remove this graffiti, despite the fact they promote an illegal act. This has become a rather overlooked phenomenon happening on campus.

Coming from a country where abortion is not restricted up to 12 weeks into a pregnancy, I must admit that the prospect of accidentally becoming pregnant in Ireland is scary to me. My great great-grandmother died in France of a clandestine abortion in 1900, and after comparing this to the current situation in Ireland, one can ask: what has really changed over a century beyond the use of abortion pills instead of knitting needles?

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), unsafe abortions are the cause of up to 20 per cent of deaths during pregnancy in several countries across the world. In Ireland, the women dealing with an unwanted pregnancy who trust the messages on Trinity’s toilet doors or on online forums are abandoned and face no choice but to risk their lives.

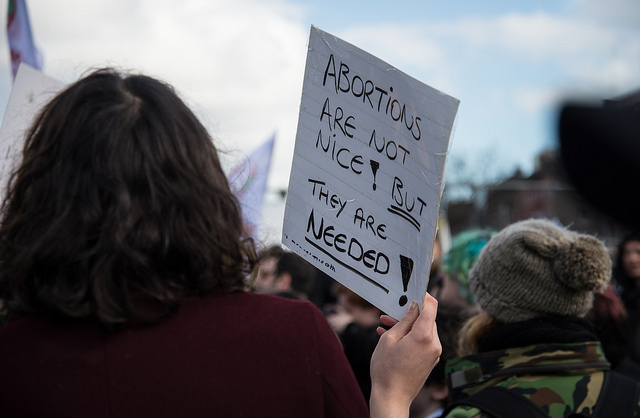

Practicing a clandestine abortion by ordering pills online without any medical assistance is like playing Russian roulette, and the consequences can be equally as disastrous. Dreadful stories emerge from testimonies of those who went through such a process: some fainted in public spaces because they were having a critical haemorrhage, others were found in their stained bed after three days because they were too weak to call for help.

Yet one of the most shocking examples I’ve heard came from a documentary on abortion in both Northern Ireland and the South: a student was reported to the police by her own (female) housemates. As a Frenchwoman, the first precedent which came to my mind was collaborators who slyly denounced their neighbours in occupied countries during World War II, and I can find no excuse for such behaviour.

Coming from a country where abortion is not restricted up to 12 weeks into a pregnancy, I must admit that the prospect of accidentally becoming pregnant in Ireland is scary to me

Ireland is always mentioned as one of the only Western countries that does not respect women’s reproductive rights. Last June, the UN Human Rights Commission called Ireland’s abortion ban “cruel and inhuman” as it reported the case of a pregnant Irish woman with a dying foetus who was forced to travel to the UK for an abortion. The last time I was in France for International Women’s Day, a TV journalist gave examples of countries which restricted women’s rights and mentioned Ireland’s anti-abortion ban alongside Saudi Arabia, where raped women can be prosecuted, and Afghanistan, infamous for its harsh treatment of women. Even if the reality is much more complex, does Ireland not deserve a better image abroad than that of a backwards nation still heavily rooted in Catholic conservatism?

The first referendum in 1992 rejected the legalisation of abortion by 67 per cent but allowed Irish women to travel abroad to receive a termination. Although a mobilisation took place in 2012 after the death of Savita Halappanavar (who was denied an abortion despite risks to her health which she eventually died from), campaigns reached a peak after July 2016 when a proposition to allow abortion in cases of fatal foetal abnormality was rejected. Consequently, the situation in Ireland seems to be different from other European countries as the abortion debate has been constantly on and off since the 1980s.

Even if the reality is much more complex, does Ireland not deserve a better image abroad than that of a backwards nation still heavily rooted in Catholic conservatism?

Countries like the UK and France legalised abortion as early as 1967 and 1975 respectively, and for the latter, mass mobilisation was primordial in making it happen. In 1971, 343 celebrities, including renowned actresses and Simone de Beauvoir, signed a manifesto published in Le Nouvel Observateur claiming that they’d had a clandestine abortion, as did one million women every year in France. The “363 whores” – as nicknamed by the media – reopened the debate and a year later, after a 17 year-old girl had been raped and her helpers were prosecuted for practicing an abortion, they won the support of the masses. Yet the parliamentary debates to legalise abortion were of an astonishing violence, and in practice many doctors used the conscience clause to refuse to do it. Thanks to the mobilisation of feminist movements, improvements in the law were progressively adopted and in 1983, abortion became funded by France’s national health service.

There is evidence that a step back in abortion rights is taking place across the world: US President Donald Trump recently signed a ban on federal money to go to groups practicing abortion, Poland threatened to ban it despite having already heavy restrictions and in 2014, the Spanish government tried to forbid abortion only four years after legalising it. Ireland’s movement to repeal the eighth amendment is sending a message contrary to expectations in times of global regression of women’s rights. As with the 2015 referendum on equal marriage, success would prove how wrong those who believe Ireland is archaic were.