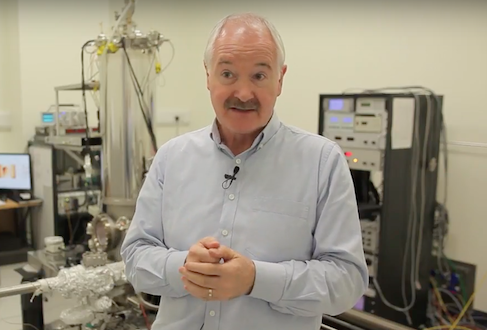

Trinity’s Dean of Research, Prof John Boland, has made a fundamental breakthrough that will potentially change how materials are designed, manufactured and used, including materials for electronics and medical tools.

The discovery, that copper nanoparticles don’t behave as previously thought, will prove significant well beyond the world of material science. The work in the Advanced Materials and Bio-engineering Research (AMBER) centre, led by the Dean of Research and Principal Investigator in AMBER, Prof John Boland, along with professors Adrian Sutton and David Srolovitz from Imperial College London and University of Pennsylvania respectively, was published in Science today.

Until now, it had been thought that the tiny granular building blocks of copper pack together neatly, “like blocks on a table top”.

This new understanding applies to materials other than copper, and is an important step in understanding how materials form. In a press statement, Boland said that if they can successfully apply this knowledge “we will have the capacity to manipulate material properties at an unprecedented level, impacting not only consumer electronics but other areas such as medical implants and diagnostics”.

“We now have a blueprint for what should happen in a wide range of materials and we are developing strategies to control the level of grain rotation”, explained Boland.

Through the use of scanning tunnel microscopy, they discovered that the grains do not form a perpendicular boundary to each other like previously assumed, but rather at an angle, “which forces the grains to rotate, resulting in unavoidable roughening”, Boland said.

“Our research has demonstrated that it is impossible to form perfectly flat nanoscale films of copper and other metals.” Each grain of copper is made of millions of copper atoms, but is less than one ten-thousandth of a millimetre in size.

Many properties of materials are controlled by how the building-blocks of the material connect together, including how well or poorly the material conducts heat or electricity. Copper and similar metals are used in wires, electrical contacts, and integrated circuits. This discovery may lead to new methods of designing copper materials, potentially reducing resistance to electric current flow and increasing battery life, thereby leading to more efficient electronic devices.

Boland believes that “this research places Ireland yet again at the forefront of material innovation and design”.

The Intel Corporation Components Research Group also collaborated on the publication. AMBER is one of Trinity’s Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) funded centres, and specialises in research of materials and bioengineering. In June, Trinity researchers in AMBER received €1.4 million to collaborate on a project that seeks to regenerate damaged nerves.