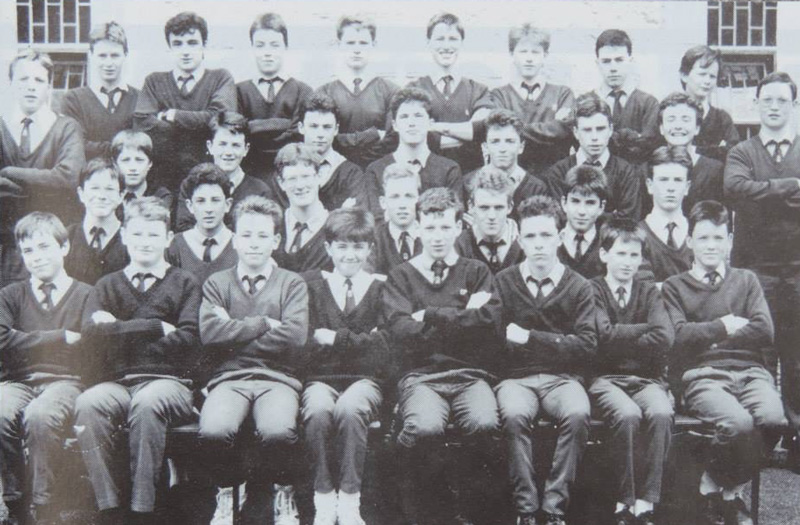

If there is consistency to Prof Patrick Geoghegan’s exploits, it surely centres on oratory. Unfurl that running thread in his life and you’ll likely end up in the early 1990s at Carmelite College in Moate, County Westmeath. Fr Gerry Hipwell is leading a debating session and Geoghegan, then a secondary school student, has his peers enthralled. “He still looked like a child”, said Kevin Flanagan, a classmate. “Yet there he was in a little suit and dickie bow holding a room.”

Though, at 43, Geoghegan can still lay claim to boyish qualities, his 6ft-plus stature is a more recent development: he earned the nickname “Squiggy” during his schooldays in part because he was such a late bloomer.

In every other respect, describing Geoghegan as a late bloomer would be woefully inaccurate. His time as a college student in University College Dublin is typified by his Gold Medal for Oratory at the Literary & Historical Society and a novel PhD thesis on the Irish Act of Union – novel because it focused on the oratory of the debates of the Union, rather than retreading the politics at play.

But Geoghegan’s most famous work is his two-volume study of Daniel O’Connell, the great orator. Coming from UCD, he was undoubtedly influenced by the Peterhouse school of history, which focuses on senior political figures and rejects the kind of biography that abstracts the actions of these figures away from personal motives. “Because he is a debater himself, he has a real interest in political rhetoric”, said Prof Ciaran Brady. “Patrick is not just a political historian. He’s fascinated by the rhetoric of major political figures.” The close attention that Geoghegan paid to O’Connell’s oratory was groundbreaking, in part because it showed how parliamentary rhetoric projected the big politics of the day.

Geoghegan met Brady in 1999, when he was in his mid-20s and a teaching assistant in Trinity’s Department of History. Brady was initially skeptical of the “young fogey”, but, as co-ordinator of the Trinity Access Programme’s history course, he was desperate to find a collaborator. It wasn’t long before Geoghegan had turned Brady’s initial impression on its head: “After each meeting, he would come back with concrete and practical ways in which we could depart from conventions and make history exciting to those who were either indifferent or hostile.”

Being a good speaker is a gift in itself, but he then has the intellectual and academic ability to impart the knowledge

“We had a whale of a time – and one of the things that I found exhilarating was how the age gap kind of disappeared. I was simply delighted to be able to work so closely with someone who was younger than me, and by about 20 years.”

Geoghegan dedicated the second volume in his study of O’Connell to Brady. The first was dedicated to Adrian Hardiman, the now-late Supreme Court Justice, whose “passion for the subject”, the text reads, “inspired the writing of it”. Geoghegan first got to know Hardiman in 2003, during the events organised to mark the bicentenary of Robert Emmet’s death. Hardiman’s authoritative writing style on matters legal and historical has undoubtedly influenced Geoghegan’s later work. Six months before he died suddenly, Hardiman had the privilege of giving the toast at Geoghegan’s wedding, which was held in Trinity and featured in last year’s RTÉ documentary about the College. Writing in March on the first anniversary of Hardiman’s passing, Geoghegan noted that there probably had not been a day when he had not felt his absence.

“I think the biggest influence on Patrick’s early life was Fr Gerry Hipwell”, said Flanagan. It may sound altogether conventional now, but three decades ago, the notion of wheeling a TV into the secondary school classroom was at least partly innovative. “Fr Hipwell would really cleverly use clips from documentaries to augment his history lessons”, said Flanagan.

Geoghegan, by all accounts a thrilling orator in his own right, is known for his packed-out lectures in Trinity and further afield. And 42 weeks of the year, he hosts Talking History every Sunday on Newstalk, which for some time was Ireland’s most-downloaded podcast. “It started then. You could tell that Patrick had a grá for it. He loved history and the way Fr Hipwell taught it from the very beginning”, Flanagan noted.

By 2003, Geoghegan had beaten out dozens in a college-wide competition for one of a handful of “new blood” professorships – prestigious permanent posts for rising academic stars. In 2008, just days before his 34th birthday, he was elected a Fellow of the College. A year later, he won the Provost’s Teaching Award – in recognition of “an outstanding contribution in the pursuit of teaching excellence”.

“Patrick is probably one of the most superb lecturers that I’ve ever come across in any field”, said John G Gordon, who serves as a Vice-President of the Irish Legal History Society alongside Geoghegan. “He’s just got that knack for taking the audience straight into the subject and capturing them. Being a good speaker is a gift in itself, but he then has the intellectual and academic ability to impart the knowledge that he has researched.”

He is also a quick-witted dinner companion. “At a dinner in Belfast, one of our very senior high court judges talked about the days of taking dinners when he went to the bar”, said Gordon. “In the olden days, obviously, the Irish had to go to London. And he told a story about going to Gray’s Inn and Patrick immediately said: ‘Oh, that’s where the Liberator took his dinners.’”

“I could see this judge”, said Gordon, “a senior Unionist judge from Northern Ireland, looking across the table and thinking ‘you’re actually comparing me to Daniel O’Connell?’ It virtually stopped the conversation dead, but it was just the funniest moment.”

Geoghegan rose to the prominence of Trinity’s executive ranks in 2011, as Provost Patrick Prendergast’s first Senior Lecturer. Geoghegan was tasked with examining how Trinity could truly become an all-Ireland university – and developed strategies that aimed to increase the percentage of students from Northern Ireland. His groundbreaking Admissions Feasibility Study, which takes a Leaving Cert student’s relative performance into account, became a pet project. Former CAO General Manager John McAvoy dubbed it an “outrageous experiment” that used students as “guinea pigs”. Geoghegan would not stand for it, and eloquently rebutted him in a sparring match that played out in the pages of this newspaper and the Irish Times.

Geoghegan’s appointment as Senior Lecturer also ushered in a new way of interacting with students. “He came to meetings in my office, as opposed to the other way around”, said Rachel Barry, the then-Education Officer of Trinity College Dublin Students’ Union (TCDSU). “That seems like a small thing, but it was not the way things had been done in College. Paying attention to those kinds of details demonstrated immediately that he was willing to really listen to students.” And he always had time for individual student cases. “He was never really bound by the hard rules, and was capable of adapting them”, said Brady.

Undeniably more serendipitous is that he is now the man behind the oratory of Ireland’s most senior political figure

Students who participated in early consultations for the Trinity Education Project, which Geoghegan initially marshalled, were in with a shot of winning Trinity Ball tickets. “I’m pretty sure he ended up buying those Trinity Ball tickets out of his own pocket”, said Jack Leahy, who served as TCDSU Education Officer two years after Barry and who had Geoghegan as a lecturer.

As a teacher, Geoghegan prefers to spend his time “chatting to people and helping them learn independently” than he does “lecturing them or working in a stuffy office”, Leahy said.

Beyond the classroom, Geoghegan is a big supporter of Trinity’s student societies – and is often seen mixing with students at their social events in Dublin pubs.

Behind the scenes – and particularly at College Board level – Geoghegan was seen as such a staunch supporter of the Provost that when he expressed dissatisfaction about the direction of the College’s botched Identity Initiative, it was enough to finally topple that phase of the project and send it back to the drawing board. He then offered the winner of a parody logo competition on Facebook a prize – a startling gesture from a person in his position.

Geoghegan’s name has long been associated with provostial ambitions. But anyone who demonstrates drive in Trinity tends to get associated with that kind of position. His appointment as a speechwriter to Taoiseach Leo Varadkar during the summer muddied those waters, to an extent – and especially since it necessitated an indefinite leave of absence from teaching in Trinity. Writing in The University Times last year, Geoghegan said that the life of an academic was one he “would not change for anything”. Given his current post, it’s perhaps serendipitous that he noted he was disinclined to explain exactly why this was the case – using the old “if you’re explaining, you’re losing” political maxim. “As long as the story is about you defending yourself you’re in trouble”, he said.

But undeniably more serendipitous is that he is now the man behind the oratory of Ireland’s most senior political figure.

“Patrick could genuinely make reading the Beano sound supremely exciting”, said Gordon. “Then, he is a good writer and he can make any subject sound interesting.”

“I think that’s what the Taoiseach will get out of him most. If I was comparing him to somebody, it would be Rob Lowe’s character in the West Wing”, he said. “Patrick Geoghegan is basically the Sam Seaborn of the Dáil.”

“He doesn’t court the limelight at all. He loves to be in the background, so this is perfect for him”, said Brady.

Then there is the small matter of working for a conservative Taoiseach.

“Patrick likes to pretend that his politics are on the right”, Brady said. “But I don’t care what he says about right-wing politics, because when it comes down to it, he has real feeling for ordinary people.”