A third of last night’s bye-election hustings was devoted to Ireland’s response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Nearly all the candidates stood behind Ireland’s military neutrality, but argued that neutral does not equate to passive. Several candidates linked their environmental pledges with Ireland’s and the EU’s dependence on Russian fossil fuels, arguing that a transition to sustainable energy is now more than ever necessary.

Split into two panels of eight, candidates each answered three questions before being given the chance to close with a final pitch to voters. The questions focussed on third-level funding and equality, the ability of the Seanad to affect national policy and what more Ireland should be doing to respond to the current Ukrainian crisis. As candidates had been provided the questions ahead of time, many answers came across as rehearsed. With almost no disagreement between candidates, last night was as much an exercise for candidates in selling their personalities as it was about policies.

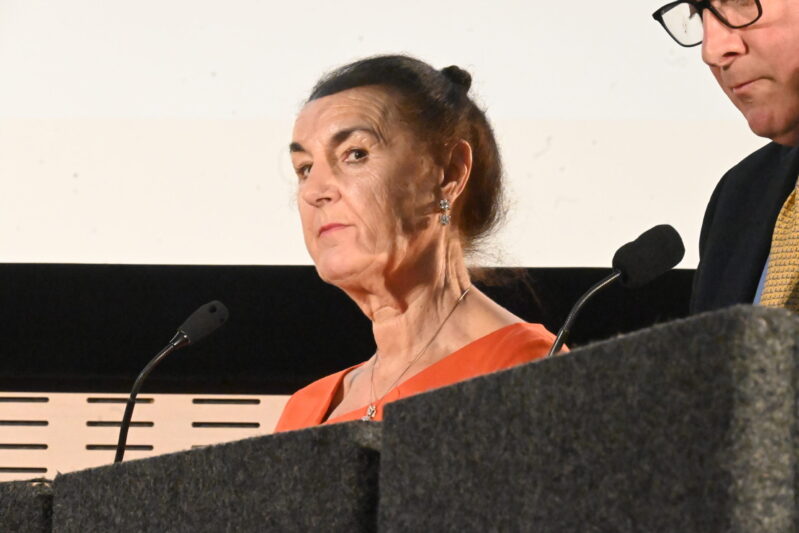

Several candidates unpacked what neutrality should mean for Ireland’s response to the crisis in Ukraine. Graduate Students’ Union (GSU) President Giséle Scanlon summed up the sentiments of several candidates when she said “neutral doesn’t necessarily mean that Ireland is passive”.

“I do not want our country to be a place that harbours oligarch money,” she added.

Candidates argued that neutrality was in and of itself a tool. PhD researcher Ryan Alberto Ó Giobúin said: “We shouldn’t view our neutrality as silencing our voice”. Instead, he argued that military neutrality gives “us a voice of reason and of justice at a time when everything seems to be going upside down”.

He said Ireland’s neutrality provides authority to its condemnations of Russia which is possible for other European nations. “When we criticise Russia, we’re not doing so as a member of NATO,” he said, “we’re doing so because it is wrong”.

Abbas Ali O’Shea agreed. He said Ireland’s neutrality and seat on the UN security council makes it “uniquely positioned” to respond to the crisis.

In comfortable territory, former army captain Tom Clonan argued that Ireland’s neutrality was important in preventing the conflict becoming even more dangerous to global security. “The risk of escalation to a conventional intercontinental ballistic missile is very high”, he said. “We do not need politicians devaluing our neutrality.”

“What could happen next would not just be catastrophic, it could be apocalyptic,” he warned.

Hugo MacNeill suggested a Citizens’ Assembly “to help discuss and tease out the very complicated issues”, associated with Ireland’s military, but not political neutrality.

Researcher Sadhbh O’Neill said Ireland could do more for Ukraine by ramping up “conversations to decrease our dependency on fossil fuels”.

Former Lord Mayor of Dublin Hazel Chu concurred: “Packages that are going to Ukraine right now are massively dwarfed by what we give Russia every day in terms of fossil fuels.”

“We may be sending aid in one way, but we’re also providing Russia with funds”, she added.

Many candidates praised Ireland’s open-door stance on Ukrainian refugees and called for continued empathy as the crisis escalates. “Irish people need to rise to the challenge with urgency and compassion”, doctoral student Ursula Quill said.

She added: “Irish people have already shown remarkable generosity as is in our nature with the offers of accommodation for refugees fleeing the nation.”

Two candidates with backgrounds in counselling and therapy, Paula Roseingrave and Eoin Barry, brought nuance to the discussion of integrating refugees into Ireland, pointing out that significant resources will be required to help people deal with trauma.

Roseingrave said a “wartime response with regard to organisation and funding” is needed. She likened the situation to the pandemic, musing that “NPHET comes to mind” in terms of the scale and overarching authority needed to oversee the crisis.

Barry said supporting Ukrainians with the “particular trauma” associated with not knowing the status of families still in the midst of war will be a particular challenge. “There needs to be training [for care workers]”, he said.

Beyond psychological care, Roseingrave said Ukrainian refugees “will need schooling for children”, as well as “help with cultural and social integration so we can understand them and they can understand us”.

Maureen Gaffney, also a psychologist, raised the practical issue of housing thousands of Ukrainian migrants. “We already have a housing crisis,” she said, “so the government is going to have a job on their hands”.

Catherine Stocker argued that “the government’s generous response to Ukrainian refugees” should not “be limited to Ukraine”.

“Why have these policies not been in place for those seeking asylum before?”, she asked.

Barrister Patricia McKenna agreed, remarking: “It almost seems that because it’s close to home, we can speak out.”

“I feel it’s not fair to those that are suffering as we speak. We need to talk about all wars and address all wars in the same way.”

Several candidates said the crisis was an opportunity to move away from the direct provision system. A surge of housing offers for Ukrainian refugees looks likely to prevent such a scenario. The Irish Times reported that more than 2,400 pledges have been made to accommodate Ukrainians fleeing the war, with the government now using the Irish Red Cross portal to coordinate the effort.

Aubrey McCarthy called for the government to make sure that “the mistakes of the direct provision model are not repeated while bringing Ukrainian refugees into Ireland.”

PhD Candidate Michael McDermott, whose humour and self-deprecation made for much-needed comic relief throughout the first panel session, had a serious moment when he said: “The system of direct provision has to be abolished because it’s cruel and inhumane.”

Barrister Ade Oluborode took a different approach to other candidates, spending less time discussing the crisis while suggesting that electing “the first African-Irish senator” would send a welcoming signal to Ukrainian refugees.

“Electing me is a signal that Ireland can be considered a truly inclusive nation,” she said, adding that it would show “that the Seanad is no longer an old boys club.”

Candidates were also questioned on their national priorities and on higher education.

Ballot papers for the election, which can be returned by post, have already been sent to registered graduates. Voting closes on March 30th.

Ailbhe Noonan, Mairead Maguire and Emer Moreau also contributed reporting to this piece.