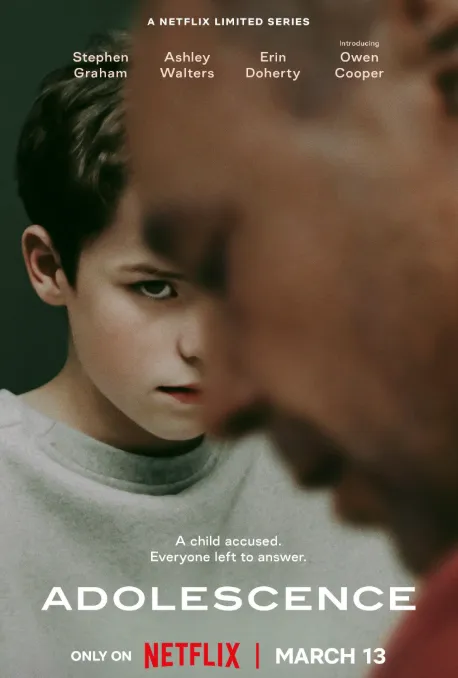

Before thirteen-year-old Jamie Miller stabs his fellow classmate Katie Leonard four times, he’s rejected. A knife sitting in his pocket, Jamie takes Katie’s refusal to go to the fair with him as an opportunity to recompense. CCTV cameras capture the attack, and the following day the Miller’s front door is barged open, and we meet our protagonist: Jamie Miller. Thirty minutes later, we find Jamie sitting in the interrogation room. With the evidence stacked against Jamie the question, in Stephen Graham’s 2025 Netflix limited series, Adolescence, is not whodunnit, but rather – who’s to blame?

Graham’s four-episode-long series places Jamie in the foreground of an increasingly leaking incel culture in Northern England. The language between him and his classmates, however, is recognisable to those outside of his town – a warning of barely concealed misogyny that Graham warns, is now universal, thanks to social media. The same rhetoric that could be found in the intersections of Dublin, just as often as in the classrooms of Atlanta.

The show follows the thirteen months post-Jamie’s arrest and travels from the briefing desk of the detectives to the graffitied car of Mr. Miller. We are introduced to Jamie immediately and then reconnect with him in the third episode, amid his final therapy session. Throughout his session with therapist Briony Ariston, Jamie’s insecurities emerge. We see a conflicted boy; one who has been both predator and prey. He seeks Briony’s approval and asks not once, not twice, but three times, whether she thinks him ugly or unlikable. He’s dragged out of the session by the security guard mid-outburst screaming, “What did you think about me? Don’t you even like me a bit?” His desperation is punctured by pre-pubescent voice cracks and tears in his eyes. He seeks justification between glances, “She was a bitch. Even you can see that.” Briony stares at the cheese sandwich Jamie bit out of when left in the empty room, and shudders. As a psychologist, she has determined her diagnosis. As a woman, she just saw a window into the future generation of increasingly radicalised men – and it’s terrifying.

His vulnerability functions like a switch– and just as easily can Jamie turn on the hurt he felt when bullied, he can turn it off. Or, at least a facade of stoicism. He emulates the same ‘alpha’ manosphere men he’s seen online; “Look at ya. All hopeful, like I’m going to say something important.” He attempts to remove himself from the conversation, from the room, to reach higher ground. He wants to look down on Briony, to expect and dodge her questions, to be the kind of male ‘omniscient’ presence that Laura Bates discusses. But his age prevents it. His age is the crux of his internal conflict – he’s a divided self between a humiliated child and then men who know better. The men he’s seen on his computer, the men that case their emotions in violence.

When cornered, Jamie stands up. He yells as he attempts to overcompensate for his age, height, and generally fetal stature. He stands over Briony, who ‘can’t fucking tell’ him ‘when to sit down’, or smirks. “Did I scare you when I shouted? I mean I’m only thirteen. I don’t think I look that scary. How embarrassing is that? Getting scared of a thirteen-year-old?”

Jamie has no female friends. “I’m not gay,” he says, with a look of disgust. He bravados adult-like confidence: he brags about being shown topless photos of his schoolmates and his mature sexual experiences. But when asked whether or not he believes women find him attractive, Jamie answers, “Of course not.”

The manosphere is retributive. As demonstrated in Adolescence, and in the cases of previous men, Nathan Larson, Ben Moynihan, George Sodini, and other incels-turned-murderers who preempted Jamie. “You denied me a happy life, and in turn, I will deny all of you life. It’s only fair”, says twenty-two-year-old Elliot Rodger in his YouTube video titled ‘Elliot Rodger’s Retribution’. Women who deny “rightful” men sex, therefore deserve the punishment that follows. “The problem is not women having sex,” Laura Bates writes in ‘Men Who Hate Women: The Extremism Nobody is Talking About’, “but women having the choice of whom to have sex with”. According to Bates, control is central to their ideology. For many who join, it becomes a “feverish obsession with sex and anger at being ‘denied’ it”. She quotes Tim Squirrell, “[This culture] emphasises mockery and the externalisation of blame as the means by which one should cope with negative emotions.”

The blame falls on women, and men become the perpetual victims of a matriarchal system. Men who have been subjected to rejection again, and again, are incubated into the ideology that the system is forced against them. They are perpetual “virgins” as the comments in Jamie’s Instagram write. Women are innately subordinate, evil beings who deserve what they get. But the initial rhetoric, that of gym content, or Andrew Tate’s ‘Tatecast’, doesn’t immediately raise flags. It’s a gradual sinking ship, one that facades itself with “Looksmaxing” tutorials, “bops”, and other colloquial terms that denigrate women. “Online communities and virtual platforms provide the means for these ideas to take shape, take hold and spread” Dr. Lisa Sugiura writes.

“We couldn’t have known” Mrs. Miller says to her husband. Markers weren’t clear to Jamie’s parents. To them, he was a quiet kid, not skilled at “footy”, who stayed fixed to his computer in his room. The turnover rate of microtrends and more benign incel terminology are hard to follow for those who didn’t grow up glued to a phone. For many parents, it’s hard to tell whether your child is addicted to Call of Duty, or going down subreddit rabbit holes.

But for us, as the audience watching Adolescence, Jamie’s deprivation is unequivocally clear. As many young teens do, he attempts to categorise himself within the social ring ladder– only his ladder is more akin to a web, stapled together with the voices of ‘red-pilled’ incels. He spends the first three episodes in denial, (as externalized blame is key to the incel identity), “I could have touched any part of her body…but I didn’t. Most boys would’ve touched her. So that makes me better.” He consistently tries to weave himself into the rigidly fixed incel hierarchy of ‘Chads’, ‘Becky’s’ and ‘Stacey’s’.

He deflects when cornered, with the same “sarcasm and deliberate provocation” that Bates pronounces. He boards himself with sarcastic artillery against his own emotions. But if Jamie, as he claims, only absorbed this ideology through osmosis, then the water must be pretty high. Graham almost argues that this language, the same one weaponised against Jamie in his comment section, is pervasive, is in the classrooms, and is now part of this generation’s tongue.

But the language isn’t always neatly translated between the older and younger generations, between parents and kids. In an attempt to find logic behind Jamie’s behavior, his parents play a blame game; ‘He never left his room,” Mrs. Miller says in the final episode, “I’d see the light on at one o’clock in the morning.” To which Mr. Miller replies, “We couldn’t do nothing about that. All kids are like that these days, aren’t they?”

“It’s not our fault, we can’t blame ourselves.”

“But we made him, didn’t we?”

After all, “he was in his room…I mean, what harm can he do in there”’ In this media age, cults of the churches and Woodstock yards are of the past. They now appear in our hands, on our phones, discreetly recruiting the most isolated.

The sad fact is, while they could have likely been more perceptive, Jamie’s ultimate outburst was catalyzed by a monster of its own. One that even Jamie’s father tries to reconcile, “he [Jamie] could have been watching anything…look at that fella that popped up on my phone, going on about how to treat women, how men should be men, and all that shit. I was only looking for something for the gym, weren’t I?” Pipelines between the masculine ends of the internet, between gym content and alt-right data forms, that Bates noticed showed “no evidence” of “effective external policing or monitoring”, pervades even the more benign content. As Detective Bascombe’s son explains, “everything has a meaning”, even emojis in the comment sections of thirteen-year-old boys.

So while the Millers should admit to some of the responsibility, any teenage boy living in the UK, Ireland, or abroad, is predisposed to the same fate as Jamie. Of peer pressure, or liking the wrong video once on an explore page. Of making the mistake that any child who hasn’t yet developed a frontal lobe might fall prey to. So many of us, amid polarisation, are grieving the loss of those around us. We grieve those who have become radicalised into a new persona. Those whose faces blur with rhetorics spewed by subreddits and Fox News stories. Those who might have wandered down the wrong rabbit hole, and never resurfaced. “How did we make her [Jamie’s sister]?” Mr. Miller asks Mrs. Miller, to which she replies, “The same way we made him.”